Inertia and Reactive Power

The keys to understanding why the Clean Power 2030 Action Plan will fail and why blackouts are inevitable.

STEVE DAVISON

Introduction

The UK’s Clean Power 2030 Action Plan has the target of producing at least as much clean electricity as the UK consumes over a year. Clean electricity should primarily come from renewables (wind and solar), along with nuclear and other low-carbon technologies. No more than 5% should be produced by unabated fossil fuel sources, i.e. generation coupled with carbon capture or some other offset mechanism.

In terms of progress towards this target, Carbon Brief explained that by September 2025, the UK had run solely on clean power for 87 hours. Rounding this up to 100 hours for the year, this equates to just over 1% of total electricity use, leaving a long way to go by 2030.

I don’t want to dwell on the achievability of this target; the answer to that question is thankfully obvious. However, as I pointed out in my previous article discussing Kathryn Porter’s warnings about energy security, there is a more fundamental reason why the clean power target is unrealistic. It comes down to the basic physics of power generation. In this technical article, I will attempt to explain why this is the case.

I appreciate that this will be a more challenging read than some of my articles, but it is essential that more people understand that there are no shortcuts when it comes to power generation. Adding more renewables to the grid represents a major challenge in both economics and engineering. Ed Miliband can spend as much of our money as he likes, but he cannot side-step the principles of physics that underpin power generation and transmission. If more people understood this, then perhaps they would change their minds about supporting renewable energy.

In the next section, I will describe the physics behind power generation and, in particular, explain the difference between active and reactive power.

In the third section, I will talk through a typical blackout scenario to demonstrate how increasing renewables makes the grid less secure.

The fundamental physics of power generation

Electromagnetic induction (the core principle)

Almost all large-scale electricity generation is based on Faraday’s law of electromagnetic induction:

A changing magnetic flux through a conductor induces an electromotive force (voltage).

In a power station:

- A prime mover (steam turbine, gas turbine, water turbine) spins a rotor.

- The rotor carries a magnetic field (from field windings or permanent magnets).

- The magnetic field rotates relative to the stator (the fixed part of the generator), which has copper windings.

- This induces an alternating voltage (AC) in the stator windings.

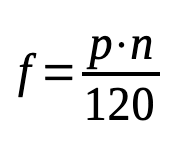

The frequency of the generated electricity is directly tied to the rotational speed as follows:

where:

f = electrical frequency (50 Hz in the UK)

p = number of magnetic poles

n = rotational speed (rpm)

The key point here is that electrical frequency is a mechanical phenomenon in traditional generators.

Real (active) power vs reactive power

In power generation, there are two types of power:

- Real (active) power

- Reactive power

Active power does the actual work and is measured in watts (W). It represents the actual energy transferred to the grid to power homes and businesses. Physically, it corresponds to torque on the generator shaft, and it slows the rotor unless mechanical input increases.

Reactive power supports the electromagnetic fields, which are fundamental to the operation of induction motors, transformers and generators. It is measured in volt-ampere reactive (VAR) units and does not transfer net energy over time.

Instead, it builds and sustains magnetic and electric fields. Physically, reactive power oscillates energy back and forth between magnetic fields (inductors, motors, generators) and electric fields (capacitors). Without reactive power, AC systems collapse, which is the key point to keep in mind for later.

Why synchronous generators need reactive power

In a synchronous generator, the rotor magnet field is produced by direct current (DC) flow through the windings in the rotor. The size of the magnetic field strength determines the generator’s terminal voltage. This field requires reactive power exchange with the grid, i.e. it is not free energy, and it must be supported continuously.

By increasing the rotor excitation (DC current flow), the generator supplies VARs to raise the terminal voltage. Decreasing the excitation means that the generator absorbs VARs, and the voltage drops.

The key point is that reactive power controls voltage, not frequency.

Inertia is the key to stable energy generation

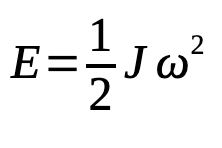

In layman’s terms, inertia represents the physical property of a rotating system that describes how hard it is to start and stop it rotating. In mathematical terms, it can be represented by the following equation:

where:

J = moment of inertia of turbines + generator rotor

⍵ = angular velocity

The moment of inertia describes how far the rotating mass is from the centre, so the further from the centre, the greater the inertia will be. Large synchronous generators store enormous kinetic energy due to their physical size and speed.

Electric grids must balance mechanical input (the rotation of the turbine) with the electrical output. If a large load suddenly connects, electrical torque instantly increases, but mechanical torque cannot change instantly. The energy deficit has to be supplied by rotor inertia. This causes a small frequency drop and allows time (seconds) for governors and controls to respond.

Without inertia, several problems arise:

- Frequency changes rapidly

- Protection systems trip

- Generators lose synchronism

- Cascading blackouts occur

Therefore, inertia acts as a shock absorber or energy buffer.

Why reactive power is essential

Reactive power is not optional because generators and transmission lines need magnetic fields. Transmission lines are inductive, so reactive power must be supplied continuously. This supports the transfer of energy between the electrical current flowing in the wires and the magnetic field that forms around the conductor. If reactive power is not supplied by the generator, then the voltage will decrease with distance.

Reactive power is also vital for load stability. Electric motors stall at low voltage, and stalled motors draw huge reactive current. This leads to voltage instability and ultimately to collapse. The April 2025 voltage collapse blackout in the Iberian Peninsula is a classic example of this situation in practice, when a single solar farm inverter failed. The problem was compounded by non-adherence to grid code standards. However, the fact remains that a single fault triggered a massive blackout across two countries with several fatalities.

As more renewable energy generators are added to the grid, the likelihood of cascading faults and blackouts increases significantly. More importantly, “black-starting” (restarting all generators from scratch) becomes exponentially harder due to the lack of a stable reference frequency.

Therefore, a power system is not just “wires and electrons”. It is a continent-scale rotating machine in which all synchronous generators are locked together at one frequency. Inertia couples them mechanically, and reactive power couples them electromagnetically.

In summary, inertia stabilises frequency by storing kinetic energy, while reactive power sustains the electromagnetic fields that allow generators to produce voltage and stay synchronised. Without either, an AC power system cannot remain stable.

Why synchronous generators are hard to replace

Synchronous generators simultaneously provide:

- Energy

- Inertia

- Voltage reference

- Reactive power

- Fault current

- Synchronising torque

Inverter-based resources can provide some of these, but not all at once, at least without compromise. Therefore, as more and more renewable energy is added to the grid at the expense of traditional synchronous power generation, the ability to maintain system stability necessarily decreases. We have limited solutions to this issue.

The first would be a massive expansion of nuclear power generation, which is synchronous.

The second solution is to maintain fossil fuel power plants, to support grid stability as well as provide backup (for when the wind isn’t blowing or the sun isn’t shining). Building sufficient nuclear capacity by 2030 is impossible. Retaining fossil fuel generators would negate the plan’s objectives without considerable expenditure on carbon capture or offsetting.

Anatomy of a grid scale blackout

So far, this has been a theoretical discussion, so let’s consider how a grid-scale blackout might happen in practice. I’ll base it on a credible modern grid scenario, but without tying it to one specific incident. In this way, we can focus on cause and effect.

Stage 0 – Normal operation (everything looks fine)

- System frequency: 50.0 Hz

- Generation ≈ demand

- Mix:

- Some synchronous generation online

- High penetration of inverter-based wind/solar

- System inertia: lower than historical norms

- Voltage controlled by a mix of:

- synchronous generators,

- SVCs (thyristor-based devices that provide dynamic reactive power compensation) and STATCOMs (more advanced devices based on power electronics).

Nothing appears abnormal to consumers.

Stage 1 – The initiating event (seconds)

A credible single fault occurs:

- A large generator trips (e.g. 1–2 GW).

- OR a major transmission line becomes faulty and disconnects from the grid.

- OR lightning causes a short circuit that is cleared by protection, such that the faulty section is isolated.

This is normal; grids are designed to survive this.

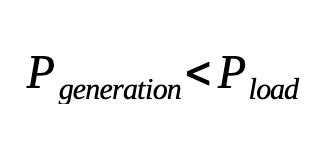

Stage 2 – Immediate power imbalance (milliseconds)

Suddenly:

and physics kicks in instantly:

- Electrical torque > mechanical torque.

- Synchronous rotors begin to reduce rotation speed.

- Frequency begins falling.

No controls have acted yet; this is pure Newtonian mechanics.

Stage 3 – Rate of Change of Frequency (RoCoF) spike (first 200–500 ms)

Because inertia is low:

- Frequency plummets.

- RoCoF exceeds safe thresholds (e.g. -0.5 to -1.5 Hz/s)

Consequences:

- Loss-of-mains protection activates on embedded generators.

- Some wind and solar inverters trip and go offline.

- Continuous Heat and Power (CHP) gas turbines disconnect because they have built-in protection that monitors frequency.

Therefore, the generation falls further, worsening the imbalance. We enter a critical positive feedback loop where one generator loss leads to others, and so on, in a cascade.

Stage 4 – Inverter control stress (0.5–2 seconds)

Inverter-based resources (such as wind and solar farms) react:

- Phase-locked loops struggle to track frequency.

- Current limits activate to protect semiconductors.

- Some inverters momentarily reduce output.

- Others trip entirely due to grid code protection (the set of technical rules and requirements that govern connection to and operation on the electricity transmission/distribution system)

At the same time, synthetic inertia responds, but too late to stop the rate of change of frequency. It does help increase the frequency nadir (i.e. prevent the frequency dropping lower than it otherwise would), but cannot prevent the initial collapse.

Stage 5 – Frequency thresholds crossed (2–10 seconds)

System frequency falls through key thresholds:

- 49.5 Hz – Primary frequency response fully deployed

- 49.0 Hz – Industrial motors draw more current

- 48.8 Hz – Some generators trip

- 48.5 Hz – Automatic load shedding (customers being disconnected) begins

But load shedding is staged, not instantaneous. Frequency keeps falling faster than shedding can help.

Stage 6 – Voltage collapse begins (parallel failure)

While frequency is falling, voltage problems emerge:

- Induction motors slow down and draw more reactive power.

- Transmission lines consume reactive power.

- Tripped generators no longer provide reactive power.

- Voltage drops locally.

Low voltage causes:

- More motor stalling.

- Even higher reactive current.

- Further voltage collapse, i.e. another positive feedback loop.

This is now a frequency-voltage coupled failure.

Stage 7 – Generator loss of synchronism (seconds to tens of seconds)

Some remaining synchronous generators experience:

- Excessive rotor angle swings, i.e. the rotor frequency becomes out of step with the grid. Therefore, the rotor frequency becomes unstable.

- Loss of synchronising torque, which would otherwise tend to bring the generator back into synchronisation.

- Pole slipping, whereby the generator gets out of step with the grid by a full electrical cycle, causing mechanical stress.

Protection acts and generators disconnect to protect shafts and turbines.

Each trip removes inertia, real power and reactive power to the point that the system is now unrecoverable without separation.

Stage 8 – System separation (islanding)

To protect what remains, transmission protection splits the grid into islands. The outcome is that some islands have too much load, leading to frequency collapse and blackout. Other islands have too much generation, leading to over-frequency and trips. Only islands with sufficient inertia, balanced load and strong voltage support remain energised. Most do not.

Stage 9 – Blackout state (minutes)

Large areas are now dark with:

- Frequency is undefined (no reference).

- Voltage is absent.

- Supervisory control systems are partially blind.

- Telecoms are running on batteries.

Inverter-based generators cannot restart on their own because they have no voltage or frequency reference. The grid is now electrically dead metal.

Stage 10 – Black start (hours to days)

Recovery is slow and manual:

- Black-start units (such as hydro, diesel and gas) energise.

- Small islands are formed.

- Voltage is built up.

- Frequency is established.

- Loads added cautiously.

- Islands synchronised together.

Restoration speed depends on the availability of synchronous plant, operator skill and communication reliability.

Conclusion

The national grid is a highly coupled system that depends on maintaining both voltage and frequency stability. Introducing increasing amounts of low-inertia power generation, such as wind, solar and batteries, is making the grid less stable. This is unavoidable unless Ed Miliband knows something about physics that I have missed.

Remarkably, the Clean Power 2030 Action Plan is simultaneously unachievable and undesirable!

Worse still, as Kathryn Porter highlighted in her excellent article, “2025: the year energy security threats began to manifest”, investment in new renewable power generation is being prioritised over maintaining the existing boring grid infrastructure, such as transformers.

This combination of factors means that grid-scale blackouts are increasingly inevitable. The question is not if, just when. Make sure you are prepared, and as Wittgenstein apparently said:

To understand is to know what to do.

This article (Inertia and Reactive Power) was created and published by Steve Davison and is republished here under “Fair Use”

••••

The Liberty Beacon Project is now expanding at a near exponential rate, and for this we are grateful and excited! But we must also be practical. For 7 years we have not asked for any donations, and have built this project with our own funds as we grew. We are now experiencing ever increasing growing pains due to the large number of websites and projects we represent. So we have just installed donation buttons on our websites and ask that you consider this when you visit them. Nothing is too small. We thank you for all your support and your considerations … (TLB)

••••

Comment Policy: As a privately owned web site, we reserve the right to remove comments that contain spam, advertising, vulgarity, threats of violence, racism, or personal/abusive attacks on other users. This also applies to trolling, the use of more than one alias, or just intentional mischief. Enforcement of this policy is at the discretion of this websites administrators. Repeat offenders may be blocked or permanently banned without prior warning.

••••

Disclaimer: TLB websites contain copyrighted material the use of which has not always been specifically authorized by the copyright owner. We are making such material available to our readers under the provisions of “fair use” in an effort to advance a better understanding of political, health, economic and social issues. The material on this site is distributed without profit to those who have expressed a prior interest in receiving it for research and educational purposes. If you wish to use copyrighted material for purposes other than “fair use” you must request permission from the copyright owner.

••••

Disclaimer: The information and opinions shared are for informational purposes only including, but not limited to, text, graphics, images and other material are not intended as medical advice or instruction. Nothing mentioned is intended to be a substitute for professional medical advice, diagnosis or treatment.

Disclaimer: The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of The Liberty Beacon Project.

Leave a Reply