Why ESG is now a tax on enterprise

TED NEWSON

British businesses have faced numerous challenges over the past few years, not least extortionate energy bills. According to the International Energy Agency, the UK has had the highest non-domestic energy prices of any member state, creating a significant barrier to growth and investment.

What’s more, the government has imposed additional regulatory costs on businesses, such as a minimum wage that has increased by over 45% since 2020. For many firms, yet another unwanted – but increasingly unavoidable – cost is Environmental, Social, and Governance (ESG) compliance, adopted not for ethical reasons but out of reputational fear.

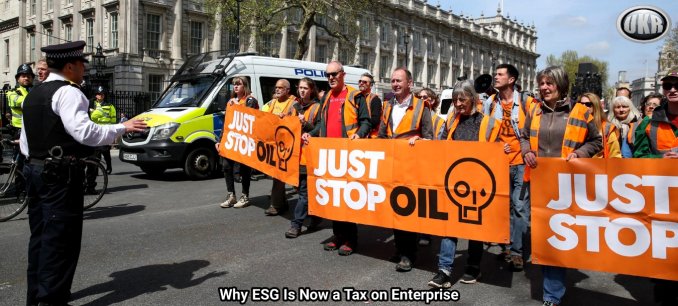

The ESG agenda takes many forms and originally existed to signal ethical conduct to consumers. Today, this is far less true, with large firms effectively bound into a de facto regulatory framework that is both costly and counterproductive. Large firms absorb the costs of hiring ESG compliance staff and making climate commitments, largely out of fear of reputational damage or disruption by activist groups.

Smaller suppliers also adopt ESG policies, not from ideological commitment but from necessity: where large firms pledge to contract only with ‘ethical’ companies, suppliers without ESG credentials risk being labelled ‘unethical’.

These commitments naturally favour larger companies, which can allocate substantial budgets – albeit a minuscule fraction of revenues – towards appearing ethical and socially responsible. Smaller firms, by contrast, must devote a far greater proportion of their revenue simply to be seen to be compliant. Such commitments, however, deliver few tangible benefits.

The oil and gas sector committing to Net Zero is a particularly baffling example. It is disingenuous for an inherently carbon-producing industry to claim that it intends to eliminate all emissions. It also shamefully obscures the enormous benefits of cheap energy to the world.

For instance, in 2020, BP voluntarily committed to lowering oil and gas production by 2030 – a commitment that it has understandably now abandoned. BP and Shell are however still committed to achieving net zero emissions by 2050. Necessary industries these are; green ones they are not.

This is a problem especially prevalent in Britain. In the US, companies prioritise growth and investment. Unlike Shell or BP, ExxonMobil has come out against ESG and net zero targets, committing instead to operational efficiency. Rather than loose commitments, they instead looked to invest in cleaner technology as it became cheaper and in line with business interests. Reducing domestic oil and gas supply risks the entire security of the economy, risking only importing from foreign countries.

As Clean Power 2030 and Net Zero 2050 appear increasingly unrealistic, British business is approaching a moment of reckoning. Will companies continue spending money to appear ‘ethical’ despite having little intention – or ability – to cut emissions, or will they step back?

As British politics becomes increasingly fractious, corporate leaders face pressure from both directions: fear of activist disruption on the one hand, and conservative backlash on the other. ESG frameworks also embed political commitments that many on the Right oppose, including diversity and inclusion schemes that prioritise skin colour or gender over merit.

Businesses already face many new cost-increasing regulations, including changes to employer’s national insurance and the Employment Rights Act, which tightens rules around hiring and firing. While ESG commitments are technically company-specific, most firms follow a heavily standardised industry-wide framework centred on decarbonisation, diversity and inclusion, and a range of subsidiary ‘codes of conduct’.

A clear example of this is Barclays, which has faced frequent protests from climate activist groups. In response, the bank has adopted restrictive ESG commitments such as Net Zero 2050 targets, sustainable finance pledges and ‘responsible investment’ criteria. These pledges go far beyond administrative costs and appear less like principled commitments than a timid response to intimidation by groups such as Just Stop Oil.

From a commercial perspective, it would be far more rational to wait until sustainable investments become genuinely attractive than to allocate capital purely for reputational posturing.

One of Britain’s most pressing challenges in an increasingly uncertain global economy is accelerating deindustrialisation. It is self-defeating for industrial firms – such as chemical companies highlighted in a recent Sky documentary – to commit to targets that they have no realistic means of meeting, sacrificing profits and growth in pursuit of abstract goals.

From energy costs to carbon taxes and expanding legislation, heavy industry already faces an unsustainable burden in Britain. Adding ESG commitments to this mix is a bridge too far, diverting investment away from productivity and towards public-relations objectives.

A blanket, economy-wide commitment to ESG rules serves no one’s long-term interests. As firms buy into ESG en masse, they retain the language of commitment while fulfilling obligations at the lowest possible cost, often through performative gestures such as tree-planting to ‘decarbonise’ flights. Were British businesses to step away from ESG collectively, capital could instead be redirected towards investment, productivity, and growth.

ESG may have begun as a voluntary signal of corporate ethics, but in today’s high-cost, low-growth Britain it functions as an unofficial tax on enterprise – one that businesses can no longer afford to pay.

Click here to subscribe to our daily briefing – the best pieces from CapX and across the web.

CapX depends on the generosity of its readers. If you value what we do, please consider making a donation.

This article (Why ESG is now a tax on enterprise) was created and published by CapX and is republished here under “Fair Use” with attribution to the author Ted Newson

Leave a Reply