Where is the money going?

High taxes, crippling debt and not much to show for it

CHRISTOPHER SNOWDON

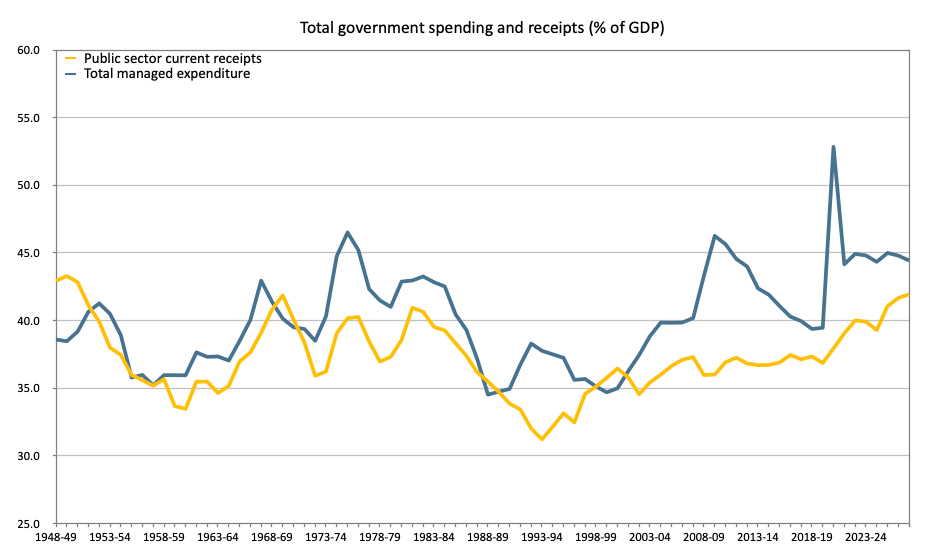

Figures published today show that public borrowing in September 2025 was £20.2 billion, the second highest September figure since records began (only beaten by the pandemic year of 2020). In the first six months of this financial year, the government borrowed £99.8 billion – £7.2 billion more than the OBR forecast in March. Taxes are at a 70 year high and the government is borrowing as if we were at war and yet nothing seems to work and Rachel Reeves is planning to raise taxes again. Why?

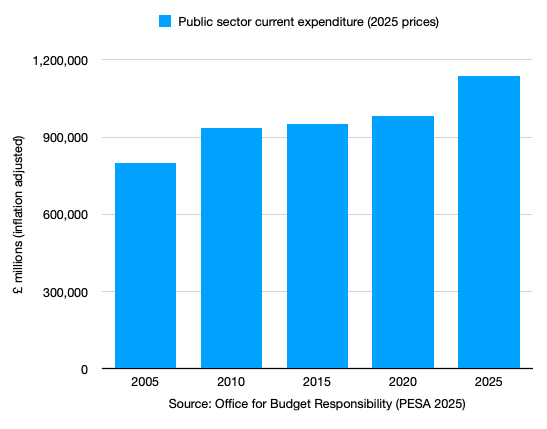

The graph below shows the last 20 years of public spending in real terms (all graphs in this article are in 2025 prices unless otherwise stated). Put simply, it rose sharply under New Labour, grew gradually in the 2010s and accelerated greatly in the last five years. If projections are correct – and they already look optimistic -the state will spend £177 billion more this financial year than it did in 2019/20 (in real terms). And this is only current expenditure. When all forms of spending are taken into account, total managed expenditure was £1,228 billion in 2024/25 and is expected to be £1,312 billion in this financial year.

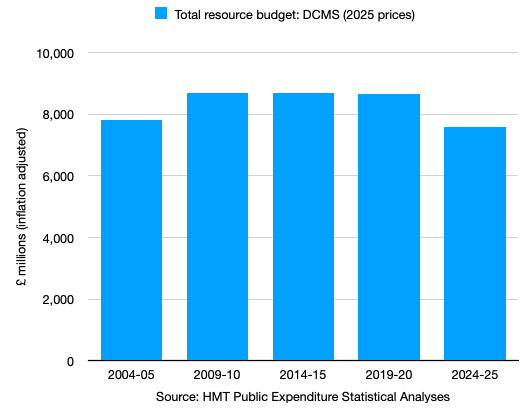

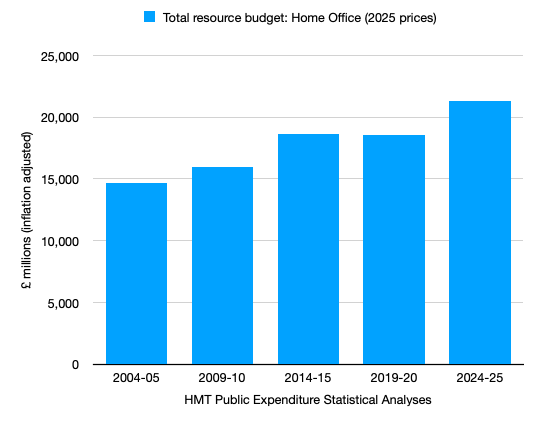

Where is it all going? Most departments have seen either little change in their budgets or above-inflation growth over the last twenty years. At DCMS, for example, the budget has been largely static while the Home Office budget has steadily increased. All the devolved administrations have been getting more money from central government, especially Scotland and Northern Ireland. So too have the Department for Transport and the Department for Energy Security and Net Zero (as it is now known).

Whither “austerity”? Although total government spending fell a little between 2010/11 and 2013/14, it never returned to the levels of 2008/09 (in real terms) and grew gradually thereafter before soaring during the pandemic.

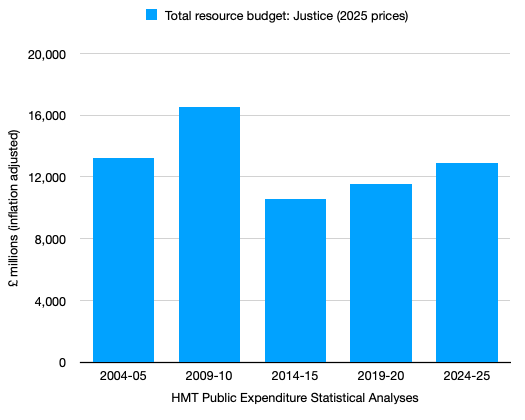

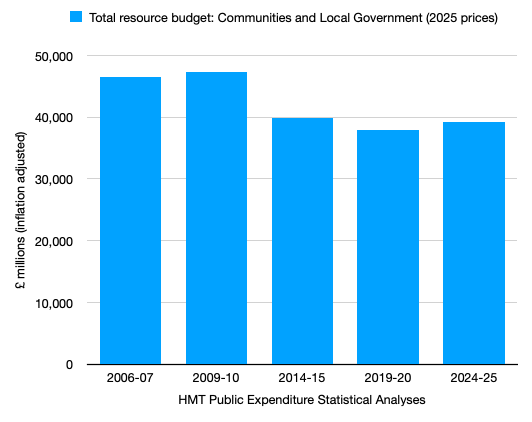

But there were cuts to some departments and they were in areas that the general public were likely to notice on an everyday basis. Justice, for example, saw significant cuts, as did local government (which is expected to pay for social care).

The pandemic required emergency funding, but what should have been a one-off turned into a step change in both spending and borrowing. Total public spending exceeded £1.2 trillion (in 2025 prices) in the extraordinary year of 2020/21 and although it fell slightly in 2021/22, it has stayed above the £1.2 trillion mark ever since. As already noted, it is expected to pass the £1.3 trillion mark this financial year.

The exceptional rates of public expenditure seen during the pandemic have become normalised. There are four areas where spending has risen sharply and they are the source of our fiscal problem.

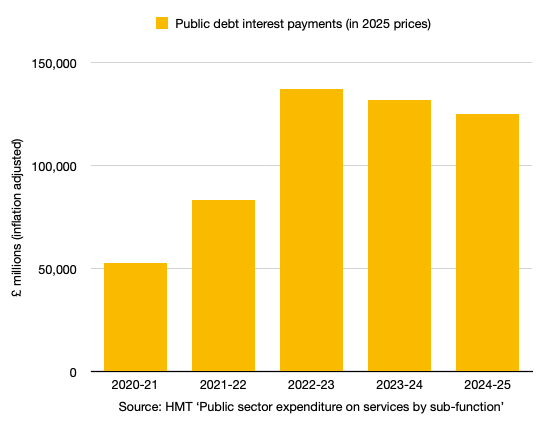

1. Public debt. It turned out that all that “cheap” money we’ve been borrowing for the last 20+ years was not so cheap. We’re spending £70 billion more on interest payments than we did in 2020/21.1 Current borrowing is mostly being spent on debt interest. We are borrowing to pay for the cost of past borrowing – and at much higher interest rates.

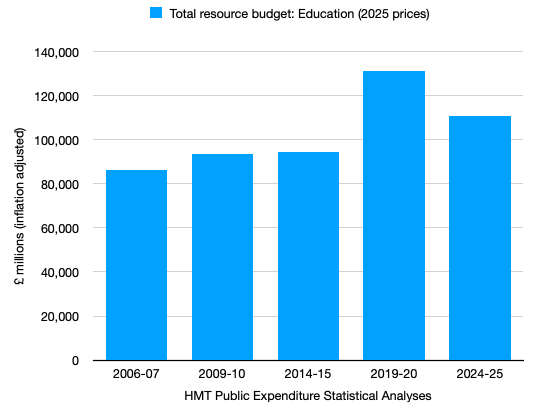

2. Education. It has gone largely unnoticed but spending on education rose sharply after 2016 and is 17% higher in real terms than it was a decade ago, costing taxpayers an extra £16.6 billion per year.

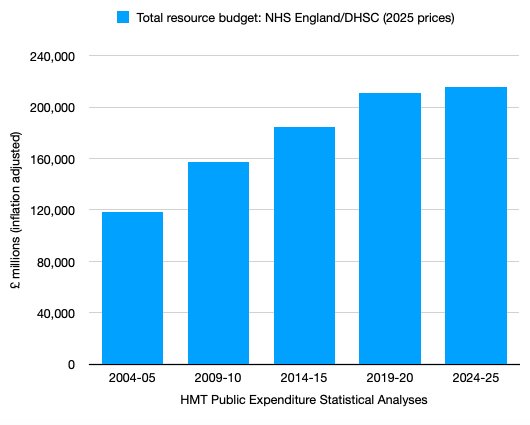

3. The NHS. The perennial money pit, immune to austerity and reform, costs nearly twice what it did 20 years ago and continues to have money thrown at it.

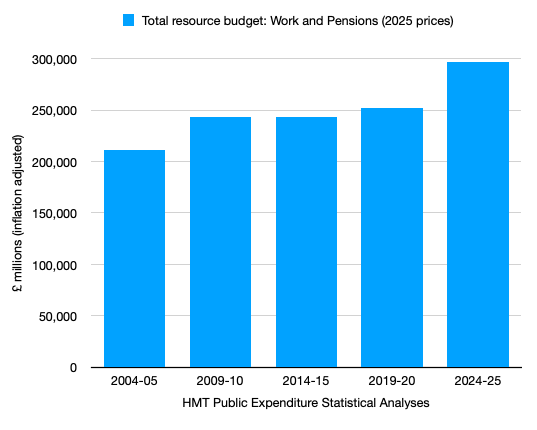

4. Social security. The budget of the Department for Work and Pensions has gone up a great deal in the last five years: a real terms increase of £55 billion.

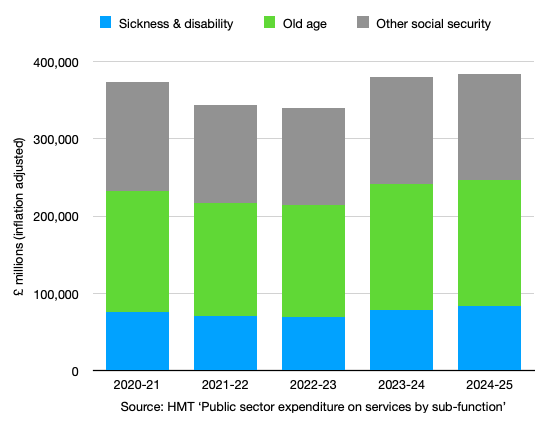

The graph above understates total spending on social security which amounted to £384 billion in 2024/25 (up from £299 billion in 2020/21). After a spike in spending during the pandemic, there was a decline but it soon rose again and is now at an all-time high. Adjusting for inflation, the welfare bill has risen by £45 billion in just the last two years. That’s your “black hole” right there.

The biggest components of the welfare spending increase are sickness/disability (up by £14 billion in two years) and pensions (up by £16 billion in two years). Again, these figures are inflation-adjusted.

What can be done? Public borrowing has already been stretched to its plausible limits. Yields on government bonds have been above the level reached after the mini-budget (which seems to be Reeves’ definition of “crashing the economy”) all year. With inflation at 3.8%, there is no appetite for another foolish round of quantitative easing. Unless there are spending cuts, Britain faces more tax rises on top of the £40 billion of tax rises announced last October, and yet there seems to be nothing that could be taxed that would not have a negative effect on the nation’s fragile economic growth.

While there are doubtless efficiency savings to be made in some departments, trimming the fat at, for example, DCMS will only make a small difference. The complete abolition of DCMS and the denationalisation of healthcare would be more helpful, but we must be realistic about what a Labour government is prepared to do.

The four areas of spending highlighted above – debt interest, education, the NHS and social security – make up more than 80% of public spending. Tax rises are inevitable for years to come unless something can be done about at least one of them.

There is nothing the government can do about debt interest payments except hope inflation and interest rates go down. The number of school pupils will begin falling this year, but there has been a “staggering” rise in the number of children classified as having special educational needs and further increases in the education budget are baked in until at least 2028. It would be nice if the health service became more efficient, but all efforts to reform that cash-guzzling leviathan have failed and few would bet on Wes Streeting breaking the cycle.

In practice, the only way this government is going to get to grips on spending is by tackling the welfare bill and getting people back into work. The last government created perverse incentives in the welfare system which encourage people to claim long-term sickness benefit rather than unemployment benefit or short-term sickness benefit. The result has been a huge rise in the number of people claiming to have difficult-to-disprove mental health conditions such as mood disorders and anxiety. This trend has been accelerated by ‘sickfluencers’ on social media and by a decline in face-to-face appointments with clinicians (another hangover from the pandemic). As the Economist notes, “[t]he cost of health-related benefits for 16- to 64-year-olds is projected to increase to £64bn by 2028-29, a 79% rise in a decade”.

There is an easy (and popular) win to be had here if the government has the will to take it seriously. Getting working age people into work would not only be good for them and good for the public finances, but it would also boost economic growth.

A more contentious way of cutting the social security budget would be to abolish the triple lock (which has just ensured a further 4.8% rise in pension payments next year). That would require breaking a manifesto commitment, but it is a manifesto commitment that one party or another is going to have to break one day.

Public debt transactions include public sector pensions which were £18.3 billion in 2024/25, up from £15.7 billion in 2020/21 but not much different when adjusted for inflation. Although it is sometimes claimed that the government owes money “to itself”, interest payments to the Bank of England make up less than 20% of the total.

This article (Where is the money going?) was created and published by Christopher Snowdon and is republished here under “Fair Use”

••••

The Liberty Beacon Project is now expanding at a near exponential rate, and for this we are grateful and excited! But we must also be practical. For 7 years we have not asked for any donations, and have built this project with our own funds as we grew. We are now experiencing ever increasing growing pains due to the large number of websites and projects we represent. So we have just installed donation buttons on our websites and ask that you consider this when you visit them. Nothing is too small. We thank you for all your support and your considerations … (TLB)

••••

Comment Policy: As a privately owned web site, we reserve the right to remove comments that contain spam, advertising, vulgarity, threats of violence, racism, or personal/abusive attacks on other users. This also applies to trolling, the use of more than one alias, or just intentional mischief. Enforcement of this policy is at the discretion of this websites administrators. Repeat offenders may be blocked or permanently banned without prior warning.

••••

Disclaimer: TLB websites contain copyrighted material the use of which has not always been specifically authorized by the copyright owner. We are making such material available to our readers under the provisions of “fair use” in an effort to advance a better understanding of political, health, economic and social issues. The material on this site is distributed without profit to those who have expressed a prior interest in receiving it for research and educational purposes. If you wish to use copyrighted material for purposes other than “fair use” you must request permission from the copyright owner.

••••

Disclaimer: The information and opinions shared are for informational purposes only including, but not limited to, text, graphics, images and other material are not intended as medical advice or instruction. Nothing mentioned is intended to be a substitute for professional medical advice, diagnosis or treatment.

Disclaimer: The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of The Liberty Beacon Project.

Leave a Reply