What Robert Jenrick gets wrong about activist judges

Judges will continue to make irrational decisions about asylum and immigration as long as the law lets them.

LUKE GITTOS

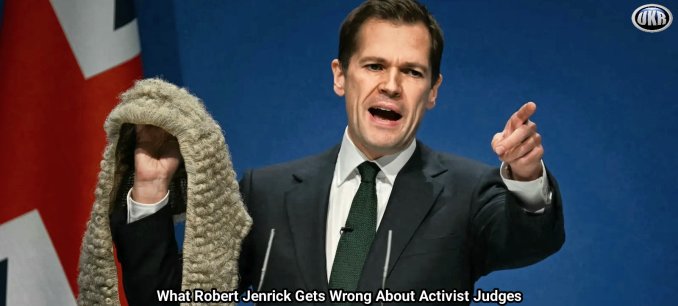

Robert Jenrick is talking tough on the judiciary. The UK shadow justice secretary’s latest proposal is to sack immigration judges who display pro-asylum bias in their decision-making.

Speaking at the Tory conference yesterday, Jenrick brandished a judge’s wig and reproached ‘dozens’ of judges who he claims advised or acted pro-bono for pro-migrant groups before joining the bench. These judges have ‘spent their whole careers fighting to keep illegal migrants in this country’, he proclaimed. Many have worked with groups such as Bail for Immigration Detainees (BID), which campaigned against the Tories’ Rwanda scheme, and Asylum Support Appeals Project (ASAP), which backs challenges against Home Office refusals of support. Beyond dismissing the offending judges, Jenrick also proposes abolishing the Judicial Appointments Committee and passing this responsibility back to the lord chancellor.

Jenrick is not wrong to raise questions about judicial decision-making. Many recent asylum cases seem to defy all logic or common sense. You would be hard pushed to find any normal person who agrees with, say, a paedophile being permitted to stay in the UK because it would ‘unduly harm’ his children if he left, or who thinks that a convicted criminal should avoid deportation because his son needs access to a particular kind of chicken nugget.

The public and politicians have every right to be critical of such decisions. It is also right that the appointment of judges has some democratic authority. Arguably, Jenrick’s proposal of passing responsibility for appointments back to the lord chancellor, an elected official, would achieve this.

But Jenrick’s intervention carries big risks. Judicial independence is a hugely important element of our constitution, which says that judges must be free of influence from the executive (of which the government is part) to interpret the law made by parliament. Jenrick suggests that there is a ‘hidden network’ of activist judges who are undermining judicial independence. But his message also seems to be that any judge whose decisions contravene the government’s wishes will face consequences for their career. This isn’t how our constitution should work.

That’s not to say we should ignore judicial bias where it occurs. Justice should not just be done, but seen to be done, too. Jenrick rightly complains about judges tweeting favourably about decisions they agree with politically, and complaining about those they disagree with. This is wrong, but it could be easily dealt with through specific reprimands against individuals. Judges will inevitably have political leanings. It’s probably best that they are transparent about these so that the public can assess for themselves whether their politics influenced a particular decision.

The problem is that Jenrick’s evidence of ‘pro-asylum bias’ in specific judges is spurious. It is based on combing through judicial biographies to find the organisations that judges worked with prior to joining the judiciary. One example he cites is judges who worked for BID, an organisation that provides free assistance to immigrants in asylum centres. But acting for these organisations pro-bono is not necessarily evidence that the judge is in favour of unrestricted immigration. Conditions in detention centres are such that people are often denied representation, so lawyers offer to help for free. This could just as easily be demonstrative of support for due process rather than for open borders or illegal migration.

Judges swear an oath when taking office to apply the law without fear or favour. Unless we have good evidence of the contrary, we should trust that they are honouring this pledge. Where there is evidence of real bias, the appeals system should correct it and the judge should be disciplined.

The biggest problem with Jenrick’s proposals is that they minimise the role that the law itself plays in these decisions. Judges in immigration cases can only make decisions on the law they are presented with. It was previous governments who handed judges more control over immigration decisions – primarily via domestic legislation like the Human Rights Act, though treaties like the Refugee Convention also limit politicians’ power. Unless these laws or treaties are amended, there will inevitably be a handful of ridiculous-looking outcomes. Jenrick acknowledges this by stressing that leaving the European Convention on Human Rights is an ‘essential first step’. But the steps after that should continue to focus on the law – rather than on individual judges – if we want to see serious change.

It could well be that certain judges in our judiciary are biased. Undoubtedly, those individuals should be disciplined. But the idea that ‘rooting out the bad apples’ will fix the problem only serves to underplay the terrible mire our asylum system is currently in.

If Jenrick and the Conservatives truly understood the complexity and magnitude of the problems with our asylum system, then sacking a few activist judges would be pretty low down on the priorities list.

Luke Gittos is a spiked columnist and author. His most recent book is Human Rights – Illusory Freedom: Why We Should Repeal the Human Rights Act, which is published by Zero Books. Order it here.

This article (What Robert Jenrick gets wrong about activist judges) was created and published by Spiked Online and is republished here under “Fair Use” with attribution to the author Luke Gittos

See Related Article Below

Why Jenrick is right to judge the judges

Blairite constitutional vandalism is not a sacred tradition

DAVID SHIPLEY

Tuesday’s speech by Robert Jenrick, in which he called for “activist” judges to be removed from their positions, has provoked much outrage. The New Statesman said he had “declared war on the judiciary”. Lib Dem leader Ed Davey tweeted “We have an independent judiciary in this country. Robert Jenrick wants puppet judges”.

Two Labour MPs, both qualified barristers, went even further. Tony Vaughan KC wrote that “our judiciary is world renowned …yet this man wants to hand pick our judges and destroy centuries of judicial independence”, while Karl Turner claimed that “the very idea of politically appointing the judiciary is utterly ridiculous. It undermines our very democracy. Political power should be divided among three distinct branches of government—legislative, executive, and judicial. Separation of powers is a very important maxim”.

The consensus amongst the “sensibles” is clear. Robert Jenrick’s plans to eliminate the Judicial Appointments Commission, to prevent activists from being judges, and to place Parliament in control of the judiciary would destroy centuries of tradition, would “undermine democracy”, and would violate that “very important maxim”, the “separation of powers.”

The idea that the judiciary should be appointed by an independent body … is a modern invention

However, that consensus is entirely wrong. The idea that the judiciary should be appointed by an independent body, without any meaningful oversight by ministers or Parliament is a modern invention. It was brought into being by the Blair government, as part of its “constitutional reform” agenda, with the claimed goal of “enhancing accountability and ensuring greater public confidence”.

As the website of the Judicial Appointments Commission explains, in 2003 “Lord Falconer, then Secretary of State for Constitutional Affairs, asserted that it was no longer acceptable for judicial appointments to be entirely in the hands of a Government Minister”. The necessary legislation received Royal Assent in 2005 and, according to the JAC, “radically changed the way Judges are appointed”. Indeed, as recently as the 1940s, the Lord Chancellor was personally involved with the appointment of all judges. As the judiciary expanded over the following 70 years, particularly as a result of the 1971 Courts Act, Lord Chancellors increasingly relied on more formal advice from the Judicial Appointments Division within their own Department. Ultimately, Lord Chancellors remained responsible for appointing judges. So when the JAC began operating the following year, it actually brought centuries of tradition to an end.

And what of Parliament’s power to constrain the judiciary? That was legislated for in the 1701 Act of Settlement. According to George Owers, author of The Rage of Party, a new history of English politics between 1688 and 1715, “when the Act of Settlement was being passed, the Tories crammed it with measures to restrain the power of a future Hanoverian monarch”. Owers explains that this is why the 1701 Act codified the principle that judges served “quam diu su bene gesserint — so long as they demonstrate good behaviour”, as opposed to at the Crown’s whim. The Act also explicitly granted Parliament the power to remove judges, saying that “upon the address of both Houses it may be lawful to remove them”

This power still exists, something the judiciary acknowledge on their website, writing that “both Houses of Parliament have the power to petition The King for the removal of the judge of the High Court or the Court of Appeal”, although they do emphasise that this power has “never had to be exercised in England and Wales …no English High Court or Court of Appeal judge has ever been removed from office under these powers.” So, far from being revolutionary, Jenrick’s suggestion that he would remove judges is a perfectly legitimate, legal and constitutional use of a power which has existed for over two centuries.

What to say about Karl Turner’s much-loved “separation of powers”? The kindest thing to say is that he’s very confused. While there is, of course, an English concept of “separation of powers” — first described by John Locke in his 1689 Second Treatise — it has nothing to do with the idea that “political power should be divided among three distinct branches of government — legislative, executive, and judicial.” What Locke argued is that there should be a separation between the Legislative which is concerned with the making of laws, and an Executive which must exist constantly in order to bring those laws into effect. He also made it absolutely clear that “the Legislative is the supreme power”.

After twenty years we have a judiciary which has become evidently politicised

This is entirely different from an American-style constitution where the Executive, Legislative and Judicial branches of government have equal standing with power divided between them. Parliamentary supremacy has, and still does define the British constitution, despite what some Labour MPs may wish, and despite the efforts of Blairite “reformers” who vandalised that constitution twenty years ago. For the creation of the Judicial Appointment Commission, along with the Supreme Court and the Sentencing Council began a process whereby the judiciary sought to take power away from Parliament.

After twenty years we have a judiciary which has become evidently politicised, with activists who stretch the law (often the Human Rights Act) to fit their preferences rather than the will of the British demos or their Parliament. We see this in numerous immigration decisions.

In June, Leonie Hirst, an Immigration Tribunal judge ruled that an Albanian with 50 convictions could stay in the UK as his crimes were “not extreme enough”, despite him having served a six-year sentence for robbery, theft and false imprisonment. In September a court blocked the deportation to France of an Eritrean man. One of the grounds the court accepted was that he might become homeless or destitute in France and that this would breach his Article 3 rights to not be subject to “torture, inhuman or degrading treatment”.

Similarly, Palestine Action were granted the right to challenge their proscription on the grounds that their rights to free expression and free assembly might be violated, and because the government should have consulted them.

This tendency of the judiciary to block the democratic will of government or Parliament was also apparent in the battle between the Sentencing Council and the Lord Chancellor in the spring. In his letters to the Lord Chancellor, the Sentencing Council’s chair, Lord Justice William Davis articulated a revolutionary and profoundly antidemocratic doctrine in which he claimed that sentencing guidelines were entirely a matter for the Sentencing Council, and that it would be damaging to the independence of the judiciary if ministers or Parliament were to seek to set sentencing policy.

This is the result of the Blairite vandalism. Judges who are increasingly divorced from what the demos and the legislature desire, but who seem to believe that they are above reproach or criticism. MPs, even MPs who are qualified barristers, who so terribly misunderstood our constitution that they will tell you with a guileless face that laws passed this century are in fact ancient foundations of the British constitution without which democracy will fall.

Jenrick is thinking in the finest tradition of English radicals, with his desire to restore ancient democratic rights. This is seen in his desire to restore the office of Lord Chancellor, and the judiciary as whole, so that those institutions are worthy of respect again. Those confused MPs, like Davey, Turner and Vaughan, should read a little more English history. Perhaps then they would be better legislators.

This article (Why Jenrick is right to judge the judges) was created and published by The Critic and is republished here under “Fair Use” with attribution to the author David Shipley

Leave a Reply