TILAK DOSHI

The Carbon Economist recently published an article innocuously entitled ‘Outlook 2026: UK electricity – Today and tomorrow‘. The Carbon Economist is an offshoot of the Petroleum Economist which has had a long and illustrious publishing history, providing oil and energy market analysis since 1934. It’s the subtitle that is striking:

Net Zero is not the problem for the UK’s power system. The real issue is with an outdated market design in desperate need of modernisation.

The author, Adi Imsirovic, currently is a guest lecturer at the Energy Systems MSc course at the Department of Engineering, Oxford University and is not some Just Stop Oil activist or an over-enthusiastic candidate for the Green Party. Imsirovic, who has 35 years of experience in oil trading, has held a few senior trading positions, including global head of oil at Gazprom Marketing and Trading and regional manager of Texaco Oil Trading for Asia. He was a Fulbright Scholar, having studied at the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences, Harvard University. Adi has a PhD in economics and a Master’s degree in energy economics. He is also author of well-received books on international oil markets.

The ‘woke’ Oxford view

Dr Imsirovic’s thesis that “Net Zero is not the problem” deserves scrutiny not only because of his credentials and his publisher’s track record. The thesis, radical as it is, needs to be judged in the context of the tumultuous year since President Trump began his second term. In the past year, the Trump administration has exited the Paris Agreement and last week withdrew from the UNFCCC and IPCC among over 60 other UN-related and other organisations that may be working “contrary to the interests of the United States”. Crucially, the US has begun to stop funding all efforts including those by the plethora of environmental NGOs to achieve Net Zero. Last year’s UN annual climate jamboree, COP30 held in Belém, Brazil, ended in disarray without even the usual aspirational closing statement to end use of fossil fuels and hasten the so-called energy transition.

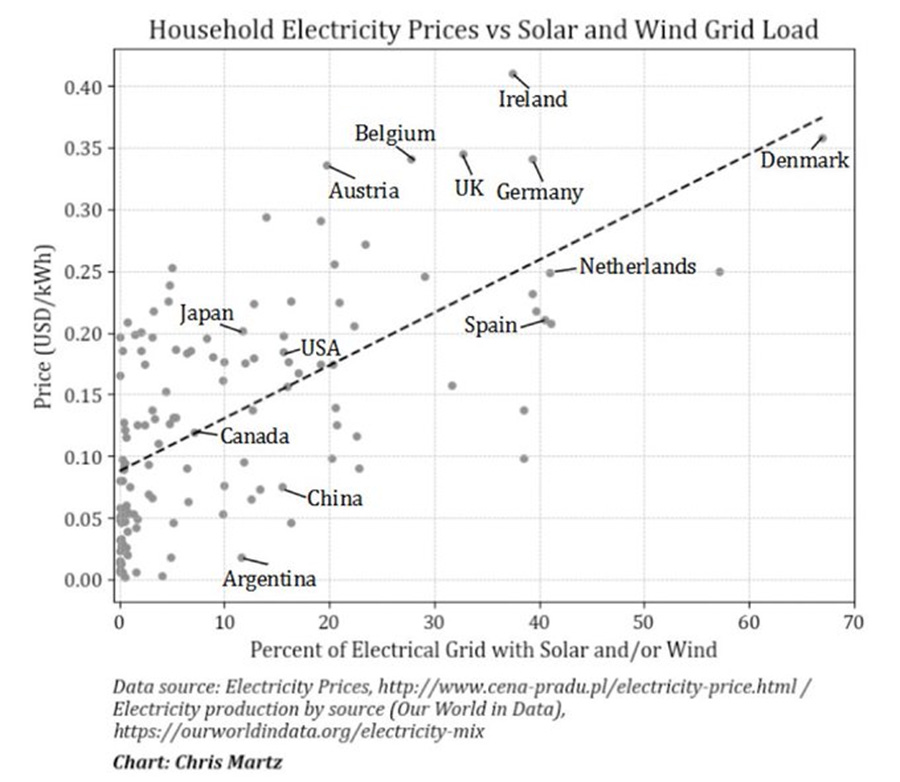

Yet, here is an opinion telling us that Net Zero is not the problem. Dr Imsirovic’s ‘Outlook 2026’ sets out to perform an act of intellectual rescue. Faced with mounting public anger over Britain having among-the-highest electricity prices in the developed world, the article seeks to exonerate Net Zero, renewable subsidies and green levies, and instead indict “poor market and system design” as the true culprit.

It is a seductive argument. By conceding that prices are high while absolving the green transition itself, ‘Outlook 2026’ offers policymakers a comforting narrative: the problem is not green ideology but mere energy plumbing.

Yet this narrative collapses under scrutiny. Far from being an unfortunate side-effect of outdated market architecture, Britain’s electricity crisis is the predictable outcome of two decades of policy-driven distortions imposed in the name of decarbonisation. “Market and system design” in ‘Outlook 2026’ functions less as diagnosis than as alibi.

Lies, Damn Lies and Statistics

The article begins with a curious argument.

The UK has some of the highest electricity prices in the world. It has become fashionable to blame this on Net Zero policies, green levies or the cost of renewables. But those explanations miss the point. Wholesale prices are only 30-45% of the retail price, not far from the share of various levies and taxes. The real cause lies in poor market and system design, not decarbonisation.

Wholesale electricity prices, ‘Outlook 2026’ observes, account for only 30-45% of retail bills, roughly comparable to the share of taxes and levies. Therefore, the report concludes, blaming renewables or Net Zero “misses the point”.

The implication of the statement that the wholesale price share of retail prices is roughly equal to that of “various levies and taxes” is not clear. It is not apparent that, therefore, the “various levies and taxes” don’t matter. Renewable subsidies are not just extra costs. They include Contracts for Difference, Renewables Obligation Certificates, capacity payments and more. These stem from policies that push weather-dependent intermittent power into a grid built for reliable (dispatchable) power sources and delivery.

The Renewable Energy Foundation estimates that the UK has spent approximately £220 billion (2024 prices) on renewable energy subsidies since 2002, with current annual costs running at £25.8 billion, now comprising roughly 40% of total electricity system costs. These are not marginal accounting artefacts. They are the dominant drivers of rising bills.

In a recent interview, independent energy consultant Kathryn Porter stated that people “have been sold a fairy tale about renewables making their bills cheaper”. Depending on natural gas, even with the high prices during 2022 caused by the outbreak of the Ukraine war, would have still saved the country £220 billion, equivalent to £8,000 per household. Without the drive for decarbonisation and so-called ‘cheap renewables’, the cost of electricity supply in the UK would now be 40% less.

What is “Market Design”?

‘Outlook 2026’boldly asserts that better “market design” can reconcile intermittent energy with industrial-scale reliability at lower cost. Time-of-use tariffs, dynamic pricing, demand response and local balancing are presented as silver bullets. Yet these concepts remain largely theoretical, supported more by modelling exercises than by real-world evidence. Dr Imsirovic states:

Most retail customers still face flat tariffs that bear little relation to time-of-day prices or grid conditions. As a result, there is no incentive to shift demand from peak, expensive and most polluting periods to less pricey ones, making electricity more expensive for everyone. … Demand response, dynamic tariffs and local balancing remain the exception rather than the rule.

Few advanced economies have implemented comprehensive time-of-use pricing for households, and fewer still have demonstrated that it materially lowers system-wide costs rather than merely shifting inconvenience onto consumers. The idea that households doing their ironing or washing at 3am or factories throttling output to chase cheaper electricity when the sun shines or the wind blows or when demand is low seems preposterous. This is a triumph of abstraction over lived reality. Electricity demand, particularly in modern industrial societies, is relatively inelastic precisely because it underpins everything else including the daily schedules of firms and households.

“Local balancing” is never properly defined. If it implies decentralised systems with local renewables plus backup, one must ask: backup of what kind, and at what scale? A typical combined-cycle gas turbine — the workhorse of reliable dispatchable power — operates optimally at scales of around 400 MW and up to 1,600 MW or more. Are local counties or towns to host their own gas plants? Or does “local balancing” in practice require vast new transmission infrastructure to smooth renewable intermittency across regions? The latter, of course, is exactly what Britain is already paying for, as grid reinforcement and new transmission line costs, as well as a host of subsidies, spiral under the Net Zero agenda.

The report’s assertion that wind and solar are now “the cheapest forms of new generation almost everywhere” is another familiar trope that collapses once system costs are included. Levelised Cost of Electricity (LCOE) estimates are endlessly recycled by renewable advocates, but they exclude the very costs that make intermittent power usable in practice: backup generation, overcapacity, storage, curtailment, inertia, frequency control and transmission expansion. As documented extensively elsewhere, the Full Cost of Electricity (FCOE) tells a very different story from misleadingly low LCOE estimates.

Here is what Dieter Helms — a tenured professor at Oxford where Dr Imsirovic guest lectures — says in relation to ‘cheap renewables’:

Solar and wind are intermittent, low-density, geographically distributed generating technologies. No modern economy could rely solely upon them. There has to be back-up. This back-up is an additional cost of renewables. … To be clear, renewables don’t pay the costs of the intermittency they cause to the system; they don’t pay for the additional capacity needed to meet an expected peak demand; they don’t pay for the extra transmission and distribution networks required; and there need to be lots of wind turbines and lots of solar panels to replicate the power output (when the wind is blowing and the sun shining) of a gas turbine.

Good Market Design Exemplars

What are the examples of better “market and system design” countries?

Across the developed world, systems that pair renewables with flexible markets perform better. Germany shows that high taxes need not mean high inefficiency. France benefits from consistent policy and a stable, legacy nuclear base. California and the Nordic countries, through dynamic pricing and cross-border trading, manage renewable variability efficiently. The UK, by contrast, manages to inherit the downsides of both competition and control.

Germany, which the report curiously cites as evidence that “high taxes need not mean high inefficiency”, now serves as Europe’s cautionary tale of economic suicide. Despite spending over €500 billion on its Energiewende, Germany has shuttered nuclear plants, expanded coal use (including inferior local lignite) for capacity and reliability while energy-intensive industries are driven offshore. BASF’s relocation of major operations abroad is not an aberration; it is a rational response to structurally uncompetitive energy costs. To present Germany as a success of renewable-friendly market design is quite a head-scratcher given all the bad press on Germany as the ‘sick man of Europe‘ in the mainstream media.

Countries and states with the highest penetration of wind and solar – Germany, the UK, Denmark, California — also exhibit some of the developed world’s highest electricity prices, rising energy poverty and accelerating de-industrialisation. The report points to California and the Nordic countries as exemplars of flexible, renewable-friendly systems. Yet California’s electricity prices have surged alongside rising blackout risks, while its grid stability increasingly depends on electricity and gas imports and emergency measures. The Nordics, meanwhile, benefit primarily from abundant hydro and legacy nuclear — dispatchable, not intermittent, resources. Their success undermines rather than supports the renewable-centric thesis.

Correlation here is not coincidence; it is causation mediated through physics.

Techno-Optimism

Techno-optimism permeates the ‘2026 Outlook’:

The electricity sector today resembles computing in the 1970s. … Future households and businesses will generate, store and trade their own energy. … Power will flow in multiple directions, coordinated digitally rather than centrally dispatched.

Techno-optimism in ‘Outlook 2026’ reaches its apogee in the vision of households as “prosumers”, trading electrons via solar panels, batteries and electric vehicles in a digitally orchestrated “energy commons”. The language — “optionality”, “networked platforms”, “from mainframe to cloud” — will sound familiar to anyone who lived through the Enron era. The analogies have a familiar ring. They echo almost verbatim the rhetoric used by Enron in its sales pitches during the late 1990s — decentralised trading, frictionless energy markets, massive arbitrage opportunities. Then, too, we were promised fungible electrons and infinite efficiency gains through clever financial and digital engineering.

What Enron brutally demonstrated is that electricity is not software. It was always constrained by the laws of thermodynamics, scale economies and real-time balancing requirements. Then, as now, the language was seductive but the physics unforgiving. While Enron collapsed in one of the largest accounting fraud cases in business history, the stories it sold about a future of dispersed, “smart” electricity were siren songs for capital markets willing to buy into an imagined new energy Valhalla.

This vision reeks of ‘technobabble’, akin to the grandiose presentations of Enron executives in the early 2000s, which hyped fungible electrons and smart trading platforms before collapsing in scandal. It echoes the pseudoscientific techno-optimism of Parag Khanna’s TED-talk-style futurism, divorced from empirical reality and the immutable laws of physics and economics.

As Mark Mills has argued, this vision belongs to the “magical thinking of the new energy economy”. No modern industrial society has ever been powered by dilute, intermittent sources coordinated by household-level arbitrage. Batteries remain prohibitively expensive at grid scale. Storage does not eliminate intermittency; it magnifies costs and material dependencies.

The battery question alone should sober any serious analyst. Grid-scale storage sufficient to cover days or weeks of low wind and solar output — the infamous Dunkelflaute — remains prohibitively expensive and resource-intensive. Even optimistic projections rely on mineral supply chains dominated by China and energy-dense inputs derived overwhelmingly from fossil fuels. Storage does not eliminate intermittency; it merely displaces it into cost, complexity and geopolitical risk.

‘Outlook 2026’ refers to the “quiet return of direct current”, but this claim too suffers from similar overreach. Many devices do operate internally on DC, and niche applications — data centres, EV fleets, industrial parks — may benefit from local DC microgrids. But the suggestion that AC grids will become mere “backup” systems is fanciful. AC transmission persists because it is unrivalled for long-distance, high-capacity power delivery with manageable losses.

Edison did not lose to Tesla by accident; physics made the decision.

An Unserious Look at Britain’s Electricity Future

‘Outlook 2026’ remains unconvincing as a serious view of Britain’s electricity future. Its argument fails not because market design is irrelevant, but because it is subordinate. Markets cannot conjure dispatchability from intermittency, nor can software substitute for energy density.

Britain’s electricity system – as Germany’s and California’s – is expensive because policy has mandated the large-scale deployment of dilute, weather-dependent energy sources while simultaneously suppressing the very technologies — large coal, natural gas and nuclear plants under central dispatch — that provide reliability at scale.

To blame “system design” while defending Net Zero is to rearrange the analytical furniture in a sinking ship. The UK’s electricity crisis is not a bug in an otherwise sound energy transition. It is the bill coming due for two decades of policy that elevated climate symbolism over energy realism. The Bank of England Governor Andrew Bailey warned last week that “both climate change and the policies implemented to tackle it (Net Zero) are acting as ‘headwinds’ that are slowing down the global and UK economy”. This is quite the opposite of “Net Zero is not the problem for the UK’s power system”, the subtitle of ‘Outlook 2026’.

A version of this article was first published in the Daily Sceptic https://dailysceptic.org/2026/01/20/the-uks-electricity-crisis-is-not-caused-by-system-failure-its-caused-by-net-zero/

Dr Tilak K. Doshi is the Daily Sceptic‘s Energy Editor. He is an economist, a member of the CO2 Coalition and a former contributor to Forbes. Follow him on Substack and X.

This article (The UK’s Electricity Crisis is Not Caused by “Poor Market and System Design”. It’s Caused By Net Zero) was created and published by Tilak Doshi and is republished here under “Fair Use”

Leave a Reply