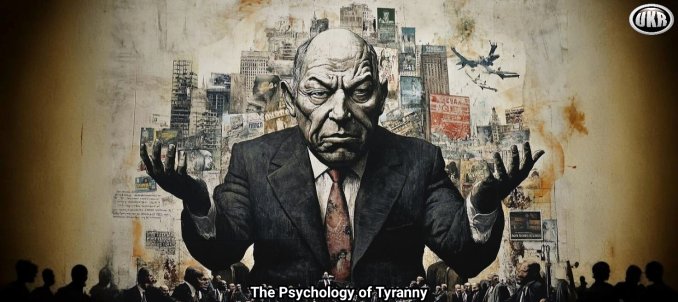

How Governments Undermine Consent and Legitimacy Through Psychological Manipulation

CONSCIENTIOUS CURRENCY

Introduction

Psychological manipulation refers to the use of tactics that influence, control, or shape individuals’ thoughts, emotions, and behaviours—often without their full awareness or consent. By exploiting core human vulnerabilities—such as the need for survival, security, belonging, and self-esteem, as outlined in Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs—manipulators craft narratives, evoke emotions, and apply pressure to steer people toward desired outcomes.

This form of manipulation permeates all facets of human interaction, frequently operating beneath conscious awareness. From consumer-seller dynamics leveraging scarcity, to employer-employee relationships using carrot-and-stick incentives, and even intimate partnerships employing guilt or emotional priming, these tactics exploit universal psychological susceptibilities. Individuals often engage in such behaviours unconsciously, mirroring the strategies used by larger entities.

Government—entrusted to serve citizens through mutual consent—also deploys psychological manipulation to enforce compliance, suppress dissent, and justify contentious policies. The consequences of such manipulation are far more profound than those arising in personal or commercial relationships. Why? Because when government distorts perception, it erodes informed consent, breaches the social contract, undermines democratic legitimacy, and conceals authoritarian tendencies.

The purpose of this article series is to dissect 12 core manipulation tactics that I have identified, explore their alignment with Maslow’s needs, examine 62 framing words and phrases prevalent in media, offer detection strategies, and expose how government’s unethical use of these methods—alongside their everyday presence in personal and professional spheres—threatens autonomy and freedom. This is Article 1 of 3 in the series.

Please note: I am not a qualified psychologist or psychiatrist. This article reflects my own analysis, informed by study and conversations with experts in the field.

State use of psychological manipulation

All governments have a long history of using psychological manipulation to influence public behaviour and maintain control. Below are concrete examples, grounded in documented cases, with a focus on brevity and clarity:

- Propaganda Campaigns (Nazi Germany, 1930s-1940s)

- The Nazi regime used state-controlled media, films like Triumph of the Will, and posters to glorify Hitler and dehumanise Jews and other minority groups, fostering nationalistic fervour and scapegoating minorities. This shaped public perception and justified aggressive policies.

- Fear-Based Messaging (U.S. War on Terror, Post-9/11)

- The U.S. government used colour-coded terror alerts and imagery of the 9/11 attacks to maintain public fear, justifying policies like the Patriot Act and military interventions. This created a climate of compliance through perceived constant threat.

- Nudge Tactics (UK, COVID-19, 2020)

- The UK’s Behavioural Insights Team used “nudge” techniques, like emphasising social conformity (“most people are complying”) and fear of missing out, to encourage compliance with lockdowns and vaccination campaigns. Leaked documents later revealed deliberate use of fear to drive adherence.

- Disinformation and Censorship (Soviet Union, Cold War)

- The USSR’s KGB spread false narratives through state media, like claiming the U.S. created AIDS, while censoring dissenting voices to control the narrative and suppress opposition.

- Social Credit System (China, Ongoing)

- China’s social credit system (if we are to believe what western press tells us about the same) manipulates behaviour by rewarding compliance (e.g., good scores for following rules) and punishing dissent (e.g., travel bans, job loss). This creates self-censorship and conformity through constant monitoring.

Do note that psychological manipulation by government isn’t always fear-based; the “carrot” approach, using incentives and positive reinforcement, is also common. Here are examples for clarity:

Carrot-Based (Incentive Approach):

- Nudge Campaigns (UK, 2010s-Present): The UK’s Behavioural Insights Team used positive reinforcement, like tax breaks for energy-efficient behaviours to encourage desired actions without overt coercion.

- U.S. WWII Bond Drives (1940s): The government used patriotic messaging and celebrity endorsements to encourage citizens to buy war bonds, framing it as a rewarding act of national pride rather than a duty.

The carrot approach often works by appealing to social approval, financial gain, or personal benefits, making compliance feel voluntary. However, governments blend both fear and incentives depending on the goal—fear for rapid control, carrots for sustained cooperation. Having said this, fear is a key motivator across most psychological operations, as it creates discomfort that makes people receptive to government-offered solutions. However, the incentive approach method, as noted above, leverage desires for inclusion and rewards, while tapping into group identity. It is therefore the interplay of fear with these other motivators that makes people malleable, as solutions address both the discomfort of fear and the appeal of positive outcomes. This nuanced combination explains why these tactics are so effective.

12 core psychological manipulation tactics

Below is a comprehensive analysis of 12 core areas of psychological manipulation I have identified as being used by government. Each section defines the concept, explains its psychological mechanism, and provides concrete examples of how government has employed these tactics, including the types of manipulations one might observe. The analysis is detailed yet concise, drawing on historical and contemporary cases, and avoids speculative or unverified claims.

(I). Gaslighting

Definition and Mechanism: Gaslighting involves manipulating individuals or groups into doubting their own perceptions, memories, or reality, often by denying facts or reframing events. Governments use gaslighting to sow confusion, undermine dissent, and maintain control by making people question their understanding of events. It exploits the human need for certainty and trust in authority, creating dependency on official narratives.

How It Works:

- Denies or distorts verifiable truths to create doubt.

- Uses repetition and authority to reinforce false narratives.

- Often paired with censorship to limit access to contradictory information.

Examples and Types of Manipulations:

- State Disinformation Campaigns (Think Cold War, 1940s-1980s):

The state denied or reframed events, often blaming innocent parties, to confuse citizens and international observers, making them question evidence. This manifested in state media repeating false narratives, while at the same time labelling dissenters as delusional or traitors, eroding trust in alternative accounts.

- Denial of Surveillance Programs (U.S., Pre-2013):

Before Edward Snowden’s leaks, U.S. officials denied widespread NSA surveillance, framing critics as paranoid. This made citizens question their concerns about privacy violations as repeated public dismissals by officials (e.g., “We don’t spy on Americans”) contrasted with later revelations, sowing distrust in personal judgment.

Common Manipulations to Watch For:

- Official denials of documented events or evidence.

- Labelling critics as conspiracy theorists or unstable.

- Contradictory messaging that creates cognitive dissonance.

- Suppression of alternative information sources.

(II). Bandwagon Effect

Definition and Mechanism: The bandwagon effect encourages people to adopt behaviours or beliefs because “everyone else is doing it.” Governments exploit this by creating the perception of widespread support for a policy or ideology, leveraging social conformity and the human desire to align with the majority. It’s similar to FOMO but focuses on conformity rather than fear of exclusion.

How It Works:

- Amplifies the appearance of majority support through media or public displays.

- Downplays or silences opposition to create a sense of inevitability.

- Appeals to the desire to belong to the dominant group.

Examples and Types of Manipulations:

- Nazi Germany’s Mass Rallies (1930s):

The Nazi regime staged massive rallies (e.g., Nuremberg Rallies) to showcase overwhelming public support, pressuring individuals to conform to Nazi ideology to avoid standing out. Films and posters depicted huge crowds cheering for Hitler, implying dissent was rare or abnormal.

- UK’s Behavioural Nudging (COVID-19, 2020):

The UK’s Behavioural Insights Team used messaging like “Most people are following lockdown rules” to encourage compliance, creating the impression that non-compliance was a minority stance. Ads highlighted statistics (e.g., “90% of people wear masks”) to pressure individuals into conforming.

- North Korea’s State Propaganda (Ongoing):

The government portrays universal devotion to the regime through choreographed public events and media, making dissent seem unthinkable. Often there are broadcasts of synchronised crowds praising the leader, with no visible opposition, creating a sense of universal agreement.

Common Manipulations to Watch For:

- Exaggerated claims of public support (e.g., “everyone agrees”).

- Media showcasing large crowds or polls of people which indicate a policy is favoured. Often the polls are fake.

- Marginalisation of dissent as fringe or unpopular.

- Social pressure to align with the “majority” view.

(III). Scarcity Manipulation

Definition and Mechanism: Scarcity manipulation creates the perception that resources, opportunities, or time are limited, prompting urgent action to secure them. Governments use this to drive compliance by exploiting the fear of loss and the psychological bias toward valuing scarce items. Unlike FOMO, which focuses on social exclusion, scarcity emphasises limited access to tangible or intangible resources.

How It Works:

- Highlights limited availability (e.g., time, goods, benefits) to create urgency.

- Triggers loss aversion, making people act to avoid missing out.

- Often paired with deadlines or rationing to amplify pressure.

Examples and Types of Manipulations:

- USSR’s Bread Lines (1970s-1980s):

The Soviet government controlled food distribution, creating artificial scarcity to pressure citizens into compliance with state policies to access rations. Long queues and limited supplies were publicised to emphasise dependence on the state, pushing loyalty to secure necessities.

- “Vaccine” Rollouts (Global, COVID-19, 2021):

Governments announced limited vaccine supplies with phrases like “Book now, slots are filling fast,” creating urgency to get vaccinated before doses “ran out.” Press releases and booking systems highlighted “limited appointments,” prompting quick registration.

- War Bond Campaigns (U.S., WWII, 1940s):

The U.S. framed war bonds as a limited-time opportunity to support the war effort, urging citizens to buy before campaigns ended. Posters with deadlines (e.g., “Buy now, support our troops”) created urgency to invest.

Common Manipulations to Watch For:

- Announcements of limited resources or time-sensitive opportunities.

- Messaging like “act now or lose out.”

- Artificial shortages to drive demand (e.g., rationing).

- Prioritising certain groups to create competition.

(IV). Framing and Narrative Control

Definition and Mechanism: Framing involves presenting information in a way that shapes how people perceive it, emphasising certain aspects while downplaying others. Governments use this to craft stories that align with their goals, manipulating emotions and priorities to gain support. This tactic exploits cognitive biases like selective attention, where people focus on the framed perspective.

How It Works:

- Selectively highlights facts or emotions to shape interpretation.

- Uses loaded language or imagery to evoke specific responses.

- Suppresses alternative narratives to maintain a single “truth.”

Examples and Types of Manipulations:

- U.S. War on Terror (Post-9/11, 2000s):

The U.S. framed military interventions in Iraq and Afghanistan as “fighting terrorism” to protect freedom, downplaying civilian casualties or geopolitical motives. Speeches and media used terms like “axis of evil” and images of 9/11 to justify invasions, overshadowing debates about oil, imperialism and the breaking of international law.

- Israel Palestine Conflict (2023-Present):

Isreal’s response to October 7th is framed repeatedly as self defence, rather than any aggression, ignoring international law and decades of historical context for the region. State media emphasises Palestinian “threats” while censoring reports of Israeli war crimes, shaping public support. You will see frequent headlines that frame the deaths on both sides as Israeli’s being “murdered”, whilst Palestinians just “die”.

3. Climate Change Campaigns (Global, 2000s-Present):

Governments frame environmental policies as “saving the planet,” focusing on catastrophic imagery to gain support, while downplaying economic costs and trade-offs. Ads with melting ice caps or suffering animals push urgency, sidelining discussions of policy feasibility and whether solutions are even planet friendly.

Common Manipulations to Watch For:

- Emotionally charged language (e.g., “crisis,” “freedom”).

- Selective use of facts or statistics to support a narrative.

- Visuals that evoke specific emotions (e.g., fear, hope).

- Atrocity propaganda.

- Censorship or dismissal of alternative viewpoints.

(V). Guilt and Moral Shaming

Definition and Mechanism: Guilt and moral shaming manipulate by making individuals feel morally responsible or inferior for not complying with a desired behaviour. Governments use this to align personal values with state goals, exploiting the human desire to be seen as “good” or avoid social judgment.

How It Works:

- Frames non-compliance as selfish, harmful, or immoral.

- Appeals to collective responsibility or societal values.

- Often uses public campaigns to amplify shame.

Examples and Types of Manipulations:

- UK WWII Rationing Campaigns (1940s):

The UK government shamed those who violated rationing rules as unpatriotic or selfish, implying they harmed soldiers and civilians. Posters with slogans like “Don’t waste food, soldiers need it” made non-compliance feel like betrayal.

- Anti-Smoking Campaigns (2000s-Present):

Various countries used graphic ads showing smokers harming their families (e.g., children exposed to second-hand smoke) to guilt individuals into quitting. Images of sick children with captions like “Your smoking hurts others” tied personal behaviour to moral failure.

- COVID-19 Compliance (Global, 2020-2021):

Governments shamed non-mask-wearers or lockdown violators as endangering others, framing compliance as a moral duty. Campaigns like “Don’t kill grandma” or “You’re not just risking yourself” made defiance seem selfish and even life ending.

Common Manipulations to Watch For:

- Messaging that ties non-compliance to harming others.

- Public shaming of individuals or groups (e.g., naming violators).

- Appeals to moral or communal values (e.g., “do your part”).

- Emotional imagery linking behaviour to negative outcomes.

(VI). FOMO (Fear of Missing Out)

Definition and Mechanism: FOMO is a psychological manipulation tactic that exploits the human desire to belong and avoid exclusion from social, economic, or cultural opportunities. It leverages anxiety about missing out on rewards, status, or trends to drive compliance or participation. Governments use FOMO to create urgency or social pressure, often framing compliance is necessary to stay part of the “in-group” or avoid being left behind.

How It Works:

- Triggers social comparison and fear of exclusion.

- Often paired with time-sensitive messaging or appeals to collective identity.

- Amplified through media, influencers, or public campaigns to create a sense of widespread participation.

Examples and Types of Manipulations:

- Vaccination Campaigns (Global, COVID-19, 2020-2021):

Governments and health authorities used FOMO to boost vaccine uptake. Messaging like “Don’t miss your chance to get back to normal” or “Join the millions getting vaccinated” implied that refusing the vaccine meant exclusion from social re-openings, travel, or community approval. Social media campaigns showcasing celebrities or peers getting vaccinated, paired with phrases like “Be part of the solution” or “Don’t be left out”, coupled with restrictions on unvaccinated individuals (e.g., vaccine passports for events) reinforced the fear of missing social freedoms.

- Consumer Incentives (Green Growth Policy, 2000s):

South Korea promoted eco-friendly behaviours by offering rewards (e.g., discounts on public transport) to citizens adopting green technologies. Campaigns framed early adopters as trendsetters, implying others would miss out on being part of a progressive movement. Advertisements highlighted “early adopter” benefits or social prestige for using electric vehicles or recycling programs, creating urgency to join the trend.

- Nationalism and Military Recruitment (U.S., WWI, 1917):

The U.S. used posters like “I Want You” with Uncle Sam to evoke FOMO, suggesting that not enlisting meant missing out on patriotic glory or letting down the nation. Slogans like “Your country needs you now!” or images of happy, heroic soldiers contrasted with implied shame for non-participants.

Common Manipulations to Watch For:

- Time-limited offers (e.g., “Act now or lose benefits”). You see this type of messaging in a lot of marketing and advertising too.

- Peer pressure tactics (e.g., “Everyone’s doing it”).

- Framing non-compliance as social isolation (e.g., exclusion from events or opportunities).

- Highlighting rewards only available to participants.

Let’s recap on what the above 6 manipulation tactics do before we move onto the next 6:

i. Gaslighting undermines confidence in reality, fostering dependence on authority. It overlaps with cognitive overload by creating confusion but emphasises reality denial, eroding trust and mental autonomy.

ii. Bandwagon Effect exploits the desire for conformity, similar to FOMO but less fear-driven. It overlaps with emotional priming by leveraging group dynamics, stifling independent thought.

iii. Scarcity Manipulation plays on loss aversion, overlapping with FOMO but focusing on resources. It overlaps with carrot and stick by using resource-based incentives, creating panic or inequity.

iv. Framing shapes perception through selective storytelling, amplifying desired emotions. It overlaps with emotional priming by using narrative to evoke feelings, distorting truth and limiting informed choice.

v. Guilt and Moral Shaming leverage moral identity, aligning personal values with state goals. It overlaps with FOMO by exploiting social pressures, alienating or polarising groups.

vi. FOMO exploits fear of social exclusion, pressuring conformity to avoid isolation. It overlaps with bandwagon effect but is more fear-driven, undermining autonomy by fostering anxiety.

Awareness Tips:

To recognise the above manipulations, look for:

- Contradictions between official narratives and evidence (gaslighting).

- Exaggerated claims of majority support (bandwagon).

- Artificial urgency or limited access (scarcity).

- Biased language or selective facts (framing).

- Appeals to morality that vilify non-compliance (guilt).

- Claims of social exclusion or missed opportunities (FOMO).

Now let’s move on to the next 6 key psychological manipulation strategies, and I will again provide a clear definition, explanation of their psychological mechanisms, and concrete examples of how government has used them.

(VII). Carrot and Stick

Definition and Mechanism: The carrot and stick approach combines rewards (“carrot”) for compliance with punishments (“stick”) for non-compliance to shape behaviour. This dual strategy manipulates by appealing to self-interest (gaining benefits) and fear of consequences (avoiding penalties). Governments use this to enforce policies while maintaining the illusion of choice.

How It Works:

- Carrot: Offers tangible or intangible rewards (e.g., financial incentives, social approval) to encourage desired behaviour.

- Stick: Imposes penalties (e.g., fines, restrictions, withdrawal of services, social stigma) to deter non-compliance.

- Balances positive reinforcement with coercive pressure for maximum effect.

Examples and Types of Manipulations:

- Social Credit System (Ongoing):

Citizens with high social credit scores receive rewards like better loan rates, priority school admissions, or travel perks (carrot), while low scores lead to punishments like travel bans, job restrictions, or public shaming (stick). Some states have public leaderboards displaying high scorers to incentivize compliance, alongside warnings of consequences like restricted access to services for low scorers.

- Tax Compliance Campaigns (2000s-Present):

Some states taxation offices offer deductions or simplified filing for compliant taxpayers (carrot) while threatening audits, fines, or jail for tax evasion (stick). Some countries have run ads emphasising “Get your refund faster” for early filers, contrasted with warnings of “penalties for late lodgement” or public naming of tax dodgers.

- Wartime Rationing (UK, WWII, 1940s):

The UK government rewarded citizens who adhered to rationing with praise for patriotism and community spirit (carrot), while penalising black-market trading with fines or imprisonment (stick). There were posters glorifying “doing your part” for the war effort, alongside public shaming or legal action for those caught hoarding or trading illegally.

Common Manipulations to Watch For:

- Financial incentives (e.g., subsidies, tax breaks) paired with fines or legal consequences.

- Social rewards (e.g., public recognition) contrasted with social penalties (e.g., shaming).

- Policies framed as voluntary but with heavy penalties for non-participation.

- Graduated systems where rewards decrease and punishments increase over time for non-compliance.

(VIII). Othering

Definition and Mechanism: Othering is the process of creating an “us vs. them” divide by portraying a group as different, inferior, or threatening to justify discrimination, exclusion, or aggression. Governments use othering to unify their population against a perceived enemy, deflecting criticism and rallying support for policies.

How It Works:

- Dehumanises or stereotypes a group to make them seem less relatable or deserving of empathy.

- Amplifies fear, mistrust, or moral superiority to justify actions against the “other.”

- Often paired with propaganda to reinforce divisions.

Examples and Types of Manipulations:

- Israel-Palestine Conflict (Western Media and Governments, 2023 ongoing):

Western governments and media have frequently portrayed all Palestinians as “terrorists” or “militants,” framing them as threats to Israel’s security to justify military actions and policies like food blockades, whilst ignoring decades of history of Israeli subjugation of indigenous Palestinians. This dehumanisation unifies Western audiences against Palestinians, deflecting scrutiny of disproportionate force. News reports and political statements use terms like “Hamas operatives” instead of “civilians” for casualties, alongside selective imagery to emphasise danger only for Israeli’s, fostering fear and reducing empathy for Palestinian suffering.

- Red Scare and Anti-Communism (U.S., 1950s):

The U.S. government portrayed communists as un-American traitors plotting to destroy democracy, leading to blacklisting and public suspicion of left-leaning individuals. House Un-American Activities Committee hearings and films like I Was a Communist for the FBI framed communists as infiltrators, encouraging citizens to report “suspicious” neighbours.

- Anti-Immigrant Rhetoric (Various Countries, 2010s-Present):

Governments in multiple nations (including the UK) have used othering to depict immigrants as criminals and cultural threats to justify border policies or deportations. For example, Hungary’s Viktor Orbán labelled migrants as “invaders” to rally nationalist support. The same is true across many western nations. Political speeches or social media posts accuse immigrants as threats to jobs or safety, and are contrasted with idealised depictions of “native” citizens.

Common Manipulations to Watch For:

- Stereotyping language (e.g., labelling groups as “dangerous” or “inferior”).

- Visual propaganda (e.g., images exaggerating differences or threats).

- Scapegoating to deflect blame (e.g., blaming minorities for economic woes).

- Policies that institutionalise exclusion (e.g., segregation, travel bans, loss of fundamental human rights).

(IX). Cognitive Overload

Definition and Mechanism: Cognitive overload involves overwhelming individuals with excessive information, complexity, or contradictory messages to reduce their ability to critically analyse or resist. Governments use this to confuse or fatigue people, making them more likely to defer to authority or accept simplified narratives. It exploits the human brain’s limited capacity to process information under stress.

How It Works:

- Floods people with data, rules, or conflicting reports to create confusion.

- Encourages reliance on official guidance to navigate complexity.

- Often used in crises to limit scrutiny of policies.

Examples and Types of Manipulations:

- Brexit Referendum (UK, 2016):

Both sides of the campaign bombarded voters with complex economic projections, trade statistics, and legal arguments, leaving many overwhelmed and reliant on slogans like “Take Back Control” to decide. Overly technical reports and contradictory claims (e.g., about EU costs) confused voters, pushing them toward emotional or simplified choices.

- COVID Policy Rollouts (Global, 2020):

Governments issued frequent, complex, and changing guidelines (e.g., mask rules, travel bans, vaccine schedules), overwhelming citizens who then relied on official summaries or compliance to cope. Rapidly shifting rules and dense scientific briefings led people to follow “just do what they say” guidance.

- Soviet Bureaucracy (USSR, 1970s-1980s):

The Soviet government used convoluted bureaucratic processes for accessing services, overwhelming citizens and discouraging dissent by making compliance the path of least resistance. Endless forms and vague regulations forced reliance on state intermediaries.

Common Manipulations to Watch For:

- Rapidly changing or overly complex rules.

- Flood of data or contradictory messages.

- Simplified “official” solutions to cut through confusion.

- Normal things requiring excessive documentation or steps so that you succumb to the new policy or strategy that the State wishes you to adopt.

(X). Authority Bias Exploitation

Definition and Mechanism: Authority bias exploitation leverages people’s tendency to trust and obey figures of authority (e.g., experts, officials) without questioning. Governments use this to promote policies by associating them with credible figures or institutions, bypassing critical scrutiny. It exploits the human inclination to defer to perceived expertise or power.

How It Works:

- Uses trusted figures (e.g., scientists, leaders, and increasingly social media influencers) to endorse policies.

- Emphasises credentials or official titles to suppress doubt.

- Often suppresses dissenting experts to maintain a unified authoritative voice.

Examples and Types of Manipulations:

- Tobacco Regulation (U.S., 1960s):

The U.S. government used Surgeon General reports to push anti-smoking campaigns, leveraging medical authority to shift public behaviour, even when some questioned the science initially. Official warnings from “experts” on cigarette packs carried more weight than individual scepticism.

- Climate Policy Endorsements (Global, 2000s-Present):

Governments cite scientists or organisations like the IPCC to justify environmental policies, framing dissenters as anti-science to discourage debate. Phrases like “97% of scientists agree” were used to silence alternative views, even when data was debated.

Common Manipulations to Watch For:

- Heavy reliance on “expert” endorsements.

- Dismissal of dissent as “unqualified” or “fringe.”

- Use of official titles or institutions, or influencers with large followings, to legitimise policies.

- Suppression of alternative expert voices.

(XI). Emotional Priming

Definition and Mechanism: Emotional priming manipulates by evoking strong emotions (e.g., hope, anger, disgust, pride) to predispose people to accept a narrative or action. Governments use this to bypass rational analysis, making policies emotionally appealing. It exploits the human tendency to make decisions based on emotional states rather than logic.

How It Works:

- Uses evocative imagery, stories, or rhetoric to trigger emotions, and very often the stories are untrue.

- Links policies to positive (e.g., hope) or negative (e.g., anger) emotional states.

- Often precedes policy announcements to “prime” acceptance.

Examples and Types of Manipulations:

- U.S. Post-9/11 Patriotism (2001):

The U.S. used patriotic imagery (e.g., flag-waving, “God Bless America”) to evoke pride and unity, priming support for the Patriot Act and Iraq War. Speeches and ads with emotional 9/11 imagery (e.g., firefighters, victims) made intrusive policies feel like patriotic necessities.

- Atrocity Propaganda in the First Gulf War (U.S., 1990-1991):

The U.S. and allied media amplified a fabricated story about Iraqi soldiers removing Kuwaiti babies from incubators, evoking outrage and compassion to prime public support for military intervention. The story, later debunked, was spread by a PR campaign and a tearful (staged) congressional testimony. Emotional imagery of infant deaths was widely broadcast and made war seem a moral necessity, bypassing scrutiny of geopolitical motives.

- Anti-Drug Campaigns (U.S., 1980s):

The “War on Drugs” used fear-inducing ads (e.g., “This is your brain on drugs”) to prime public support for harsh drug laws. Emotional imagery of addiction’s devastation made punitive policies seem urgent.

Common Manipulations to Watch For:

- Evocative imagery or stories tied to new policies being enacted or tied to gaining agreement to war or other military campaigns.

- Speeches that stir emotions before policy announcements.

- Appeals to national pride, fear, or compassion.

- Emotional narratives overshadowing policy details.

(XII). Desensitisation

Definition and Mechanism: Desensitisation involves gradually exposing people to controversial or extreme ideas, policies, or events to reduce shock or resistance over time. Governments use this to normalise actions that might initially provoke outrage, exploiting the human tendency to adapt to repeated stimuli.

How It Works:

- Introduces ideas or policies incrementally to avoid backlash.

- Uses repetition to make the unacceptable seem normal.

- Often paired with media saturation to dull emotional responses.

Examples and Types of Manipulations:

- War on Terror Drone Strikes (U.S., 2000s-Present):

The U.S. gradually normalised drone warfare by starting with limited strikes and increasing their frequency, desensitising the public to civilian casualties. Media reports framed strikes as “precise,” downplaying collateral damage.

- UK Surveillance Expansion (2000s-Present):

The UK has incrementally expanded surveillance through various laws legalising mass data collection, such as the Investigatory Powers Act 2016 (the “Snooper’s Charter”), which expanded government access to communications data, including internet browsing histories. Facial recognition and CCTV proliferation have further normalised constant monitoring. Media and government frame these as “public safety” measures, reducing public concern over privacy erosion, with campaigns emphasising terrorism prevention to justify intrusion.

- UK National ID Initiatives (2010s-Present):

The UK has repeatedly tried to introduce a National ID system (now digital), often tied to immigration control, to normalise pervasive identity tracking. Immigration fears have been leveraged to frame digital ID as a tool to combat “illegal migration,” desensitising the public to privacy losses and centralised control. Media and government narratives, such as “securing borders” or “stopping illegal immigrants,” is in the process of normalising digital ID checks (e.g., via smartphone apps or biometric databases), downplaying risks like data breaches or exclusion of vulnerable groups (e.g., elderly without tech access).

Common Manipulations to Watch For:

- Gradual escalation of controversial policies.

- Repeated exposure to normalise extreme measures.

- Media framing that downplays ethical concerns.

- Incremental restrictions on freedoms.

Let’s recap on what the above 6 manipulation tactics do before we move onto the next part of this article:

i. Carrot and Stick use rewards and punishments to enforce behaviour, exploiting survival needs. It overlaps with scarcity but focuses on direct control, coercing compliance and limiting choice.

ii. Othering portrays groups as threats to justify discrimination, fostering division. It overlaps with framing but emphasises dehumanisation, eroding empathy and enabling harm.

iii. Cognitive overload overwhelms with complex information, fostering reliance on authority. It overlaps with gaslighting but focuses on exhaustion, impairing critical thinking.

iv. Authority bias leverages trust in experts to drive compliance, discouraging scepticism. It overlaps with framing but emphasises credibility, stifling independent judgment.

v. Emotional priming evokes emotions to bias decisions, often using false narratives. It overlaps with framing but focuses on arousal, distorting rational choice.

vi. Desensitisation normalises extreme policies through gradual exposure, dulling resistance. It overlaps with framing but emphasises repetition, eroding moral awareness.

Awareness Tips:

To recognise these manipulations, look for:

- Rewards or penalties tied to behaviour (carrot and stick).

- Dehumanising or threat-based language about groups (othering).

- Confusing or excessive information pushing deference (cognitive overload).

- Overreliance on expert or leader endorsements (authority bias).

- Emotionally charged, unverified stories (emotional priming).

- Gradual policy escalation or repeated normalisation (desensitisation).

Combining Tactics Creates Impact

Governments often combine several psychological manipulation tactics simultaneously to amplify their effect. For example, during “COVID”, authorities employed:

- Framing (“We’re all in this together”)

- Bandwagon effect (“Most people comply”)

- Guilt appeals (“Protect your community”)

- Scarcity messaging (“Limited jab doses”)

- Carrot and stick incentives (e.g., free doughnuts for jab compliance vs. job loss in the care sector for non-compliance)

These strategies were effective because they tapped into universal human traits—trust, conformity, loss aversion, and moral sensitivity.

While this article has outlined 12 core psychological manipulation techniques, it’s important to note that the list is not exhaustive. Tactics can overlap, evolve, or be context specific. Additional categories worth considering include:

- Distraction: Diverting attention from controversial issues to obscure scrutiny (e.g., amplifying celebrity scandals to overshadow policy failures)

- Reciprocity Manipulation: Offering small concessions to create a sense of obligation (e.g., minor tax breaks to secure loyalty to unpopular regimes)

- False Dichotomies: Presenting issues as binary choices to limit debate (e.g., “You’re either with us or against us”)

- Hegelian Dialectic: Orchestrating a problem, reaction, and solution to steer outcomes (e.g., exaggerating a security threat to justify surveillance laws or digital ID systems)

These categories often intersect with the core 12 tactics discussed above—for instance, distraction aligns with framing, and reciprocity manipulation mirrors carrot-and-stick dynamics. Nonetheless, the 12 identified tactics remain broadly applicable across most government manipulation contexts, as they target foundational psychological vulnerabilities: fear, conformity, trust, emotion, and cognitive capacity.

Governments routinely blend the 12 tactics for maximum effect. During wartime, for example, they may combine emotional priming (patriotic fervour), othering (enemy vilification), and authority bias (military endorsements) to rally public support. Each tactic exploits specific human tendencies, making them highly adaptable across different scenarios.

Ethical Concerns

Repeated exposure to psychological manipulation tactics can influence brain function and neural pathways over time. This occurs through neuroplasticity, the brain’s ability to adapt and reorganise neural connections in response to experiences. This is because psychological manipulation targets cognitive, emotional, and social processes, which engage specific brain regions. Repeated exposure can strengthen or weaken relevant neural pathways, alter emotional regulation, and influence decision-making. Here’s how this happens:

- Neuroplasticity and Habit Formation:

- The brain adapts to repeated stimuli by strengthening neural connections (synaptic plasticity) in areas like the prefrontal cortex (decision-making), amygdala (emotions, fear), and hippocampus (memory).

- Frequent exposure to manipulation reinforces specific thought patterns or behaviours, making them more automatic (e.g., habitual compliance or fear responses).

- Over time, this can create neural pathways that favour certain reactions, reducing critical thinking and increasing susceptibility to further manipulation.

- Stress and Emotional Impact:

- Many tactics (e.g., FOMO, othering, gaslighting) activate the amygdala, triggering stress or fear responses. Chronic activation can lead to heightened anxiety or hypervigilance, reshaping neural circuits in the amygdala and prefrontal cortex.

- Prolonged stress may impair the prefrontal cortex’s ability to regulate emotions or make rational decisions, making individuals more malleable.

- Social and Reward Systems:

- Tactics like carrot and stick or bandwagon effect engage the brain’s reward system (e.g. dopamine pathways), reinforcing behaviours tied to rewards or social approval.

- Repeated reinforcement strengthens these pathways, making people more likely to seek external validation or conform.

Each psychological manipulation tactic engages different brain regions and processes, with long-term exposure potentially leading to distinct changes. Below, I outline the likely neural impacts of the same, linking back to my 12 identified categories of manipulation.

1. Gaslighting

- Brain Regions Affected: Prefrontal cortex (reality-testing), hippocampus (memory), amygdala (anxiety).

- Mechanism: Gaslighting creates cognitive dissonance, overloading the prefrontal cortex and hippocampus as individuals struggle to reconcile conflicting realities. Chronic exposure can weaken confidence in memory and perception.

- Long-Term Changes:

- Reduced prefrontal cortex activity, impairing critical thinking and self-trust.

- Heightened amygdala reactivity, increasing anxiety and dependence on external validation.

- Disrupted hippocampal encoding, leading to fragmented or distorted memory recall.

2. Bandwagon Effect

- Brain Regions Affected: Ventral striatum (social reward), prefrontal cortex (conformity decisions), mirror neuron system (inferior frontal gyrus and parietal lobule – social mimicry).

- Mechanism: The bandwagon effect activates reward pathways when aligning with the majority, reinforcing conformity. Repeated exposure strengthens neural circuits for social mimicry and reduces scrutiny of group norms.

- Long-Term Changes:

- Increased automatic conformity, with reduced prefrontal cortex oversight.

- Strengthened reward pathways for social alignment, diminishing independent thought.

3. Scarcity Manipulation

- Brain Regions Affected: Amygdala (fear of loss), prefrontal cortex (urgency decisions), ventral striatum (reward anticipation).

- Mechanism: Scarcity triggers loss aversion, activating the amygdala and prompting impulsive action. Repeated exposure reinforces urgency-driven decision-making.

- Long-Term Changes:

- Heightened amygdala sensitivity to perceived loss, increasing stress-driven decisions.

- Reduced prefrontal cortex control, leading to impulsivity under pressure.

4. Framing and Narrative Control

- Brain Regions Affected: Prefrontal cortex (interpretation), amygdala (emotional response), hippocampus (memory formation).

- Mechanism: Framing biases how the prefrontal cortex interprets information. Repeated exposure strengthens narrative-consistent neural patterns, making alternative perspectives harder to process.

- Long-Term Changes:

- Reinforced cognitive biases, reducing openness to new viewpoints.

- Emotional associations (amygdala) tied to narratives influence memory encoding and decision-making.

5. Guilt and Moral Shaming

- Brain Regions Affected: Insula (guilt, shame), ventromedial prefrontal cortex (moral reasoning), amygdala (emotional distress).

- Mechanism: Guilt activates the insula and amygdala, creating emotional discomfort. Repeated exposure links non-compliance to shame, reinforcing external moral alignment.

- Long-Term Changes:

- Increased sensitivity to social judgment, amplifying insula activity.

- Over-reliance on external moral cues, weakening autonomous ethical reasoning.

6. FOMO (Fear of Missing Out)

- Brain Regions Affected: Amygdala (fear of exclusion), prefrontal cortex (social decision-making), ventral striatum (reward anticipation).

- Mechanism: FOMO triggers anxiety about exclusion, activating the amygdala. Repeated exposure strengthens conformity circuits and dopamine-driven reward anticipation.

- Long-Term Changes:

- Increased sensitivity to social cues, potentially leading to chronic anxiety or approval-seeking.

- Reinforced reward pathways for group alignment, reducing independent decision-making.

7. Carrot and Stick Methods

- Brain Regions Affected: Ventral striatum (reward), amygdala (fear of punishment), orbitofrontal cortex (cost-benefit analysis).

- Mechanism: Rewards activate dopamine pathways, reinforcing compliance, while fear of punishment triggers amygdala-driven stress. Repeated exposure strengthens reward-punishment circuits.

- Long-Term Changes:

- Heightened sensitivity to external incentives, reducing intrinsic motivation.

- Weakened prefrontal control, leading to automatic compliance to avoid discomfort.

8. Othering

- Brain Regions Affected: Amygdala (threat detection), insula (empathy, disgust), prefrontal cortex (group identity).

- Mechanism: Othering activates fear and disgust toward out-groups, reinforcing amygdala and insula responses. Repeated exposure strengthens “us vs. them” neural patterns.

- Long-Term Changes:

- Diminished empathy circuits (e.g., reduced insula activation) for out-groups.

- Strengthened tribal identity pathways, increasing bias and polarisation.

9. Cognitive Overload

- Brain Regions Affected: Prefrontal cortex (cognitive control), amygdala (stress), hippocampus (information processing).

- Mechanism: Overload taxes the prefrontal cortex, reducing analytical capacity and increasing reliance on simplified or authoritative cues.

- Long-Term Changes:

- Impaired prefrontal cortex function, leading to reduced critical thinking.

- Increased stress reactivity (amygdala), fostering dependence on external guidance.

10. Authority Bias Exploitation

- Brain Regions Affected: Prefrontal cortex (trust decisions), orbitofrontal cortex (social evaluation), ventral striatum (reward for compliance), amygdala (fear of defiance).

- Mechanism: Trust in authority activates reward pathways for compliance and fear circuits when resisting. Repeated exposure reinforces deference.

- Long-Term Changes:

- Reduced prefrontal scepticism, increasing blind trust.

- Strengthened reward pathways for obedience, diminishing autonomous judgment.

11. Emotional Priming

- Brain Regions Affected: Amygdala (emotional arousal), prefrontal cortex (decision-making), insula (empathy).

- Mechanism: Priming evokes emotions that bias decisions, strengthening emotional pathways. Repeated exposure makes emotionally driven decisions more automatic.

- Long-Term Changes:

- Heightened amygdala sensitivity to emotional cues, reducing rational deliberation.

- Stronger emotional biases in decision-making, especially under stress.

12. Desensitisation

- Brain Regions Affected: Amygdala (emotional response), insula (moral outrage), ventromedial prefrontal cortex (ethical judgment).

- Mechanism: Repeated exposure to distressing stimuli reduces amygdala and insula activation, normalising extreme actions. Habituation weakens emotional objections.

- Long-Term Changes:

- Blunted emotional responses to unethical policies, reducing resistance.

- Weakened ethical reasoning circuits, increasing passive compliance.

In addition to the above, repeated exposure to any of the 12 tactics can lead to:

- Altered Neural Pathways:

- Strengthened pathways for fear, conformity, or reward-seeking (e.g., amygdala, ventral striatum) make manipulated behaviours more automatic.

- Weakened prefrontal cortex pathways for critical thinking reduce resistance to manipulation.

- Chronic Stress Effects:

- Tactics like FOMO, gaslighting, or othering increase cortisol, potentially shrinking the hippocampus (memory) and impairing prefrontal cortex function, leading to poorer decision-making.

- Reduced Autonomy:

- Reinforced reliance on external cues (authority, social norms) can diminish independent thought, as neural pathways for self-directed reasoning weaken.

- Desensitisation to Ethics:

- Tactics like othering or desensitisation reduce empathy (insula) and moral judgment (prefrontal cortex), enabling acceptance of harmful policies.

The good news – recovery is possible

Not all psychological or neurological changes are permanent. Thanks to neuroplasticity, the brain can recover and rewire itself through new experiences—such as education, therapy, and conscious reflection. However, prolonged exposure to manipulation tactics, especially within high-stress or tightly controlled environments (e.g., authoritarian regimes), can lead to lasting neural adaptations that reinforce compliance and diminish autonomy. This is why it’s crucial to limit time spent engaging with devices or platforms that deliver “news” or “events” saturated with the manipulation strategies discussed above. Reducing exposure helps preserve cognitive clarity, emotional resilience, and independent thought.

What’s Next

In the next article, I’ll explore:

- Words and phrases to watch for in government and media framing manipulation

- Detection strategies and countermeasures to resist psychological manipulation

- Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs and its relevance to understanding how manipulation exploits core human vulnerabilities

This article (The Psychology of Tyranny) was created and published by Conscientious Currency and is republished here under “Fair Use”

••••

The Liberty Beacon Project is now expanding at a near exponential rate, and for this we are grateful and excited! But we must also be practical. For 7 years we have not asked for any donations, and have built this project with our own funds as we grew. We are now experiencing ever increasing growing pains due to the large number of websites and projects we represent. So we have just installed donation buttons on our websites and ask that you consider this when you visit them. Nothing is too small. We thank you for all your support and your considerations … (TLB)

••••

Comment Policy: As a privately owned web site, we reserve the right to remove comments that contain spam, advertising, vulgarity, threats of violence, racism, or personal/abusive attacks on other users. This also applies to trolling, the use of more than one alias, or just intentional mischief. Enforcement of this policy is at the discretion of this websites administrators. Repeat offenders may be blocked or permanently banned without prior warning.

••••

Disclaimer: TLB websites contain copyrighted material the use of which has not always been specifically authorized by the copyright owner. We are making such material available to our readers under the provisions of “fair use” in an effort to advance a better understanding of political, health, economic and social issues. The material on this site is distributed without profit to those who have expressed a prior interest in receiving it for research and educational purposes. If you wish to use copyrighted material for purposes other than “fair use” you must request permission from the copyright owner.

••••

Disclaimer: The information and opinions shared are for informational purposes only including, but not limited to, text, graphics, images and other material are not intended as medical advice or instruction. Nothing mentioned is intended to be a substitute for professional medical advice, diagnosis or treatment.

Disclaimer: The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of The Liberty Beacon Project.

Leave a Reply