Farage, the Small States Club, and the Middle Powers

DOGMATIC SLUMBERS

Nigel Farage doesn’t often surprise me, but he managed the feat in this recent interview. Asked about what he enjoyed reading (‘Poetry – not much’) he disclosed that his current book was written by a former president of Armenia. I had expected Farage to know no more than Donald Trump about Armenia .

The Small States Club is a 2023 book by Armen Sarkissian. Subtitled How small smart states can save the world, it’s a brief study of ten Small States, nine of which have prospered, one of which (Armenia, sadly) is under existential threat.

Sarkissian was Prime Minister of Armenia at a time when the power was with the Presidency, and President at a time when the role was entirely ceremonial. His tenure as PM, under the first president of Armenia after the dissolution of the Soviet Union, lasted only a few months, cut short by a cancer diagnosis and an aggressive treatment programme. Prior to (and after), he had been ambassador to the UK; prior to that, a nuclear physics professor who had invented a version of Tetris (‘Wordtris’) – a version where letters are fitted into words, rather than shapes into gaps. He is an unlikely, and unworldly, politician.

The interview piqued my interest, into what lessons Farage might draw, and the balance of geopolitics more generally. And how received wisdom in the UK is selling us short.

The Small States Club

Sarkissian’s short book is a tour of ten states: Singapore, Qatar, the United Arab Emirates, Israel, Estonia, Switzerland, Ireland, Botswana, Jordan and Armenia itself. On the surface, Sarkissian presents nothing that could fall outside of conventional liberal-global doctrine drafted by the Tony Blair Institute; from a belief in technology, delivered by Public Private Partnerships, to the dangers of ‘toxic’ populism and the benefits of ‘celebrating multi-ethnicity’. Illustrations present Sarkissian glad-handing world statesmen, from Thatcher and (then) Prince Charles, to Macron and Modi; some (ridiculous though it seems) in Covid-era facemasks.

The examples chosen demonstrate one of the author’s points: there is no one formula for success. Only three of his states are resource-rich; most of the successes are demonstrations of economic openness and business-friendly regimes. Ethnically, they range from managed diversity (Singapore and to an extent Switzerland) to homogeneity; three have substantial diasporas. And in terms of external threats, they vary from being at extreme, existential risk, to being fundamentally unthreatened – Ireland is not even a full member of NATO. It is worth noting that four of Sarkissian’s selection – Qatar, Singapore, Israel and the UAE – are in the top 10 defence spenders per capita in the world (and two others of the top 10 – Kuwait and Oman – could also have made his list). The message should be clear: if you’re a small state, you will probably need to spend big on defence.

Except for Switzerland, all are creations (as modern nation states) of the dissolution of empires – seven from Britain – and only Ireland through force. Sarkissian prefers to castigate Britain for the Irish potato famine than praise us for the incredibly generous terms on which decolonisation took place (naturally, he inhabits an unquestioned world where colonialism = bad). He does grant that Singapore opted to retain British military protection in the early days of its independence, and we will look further at the creation of the UAE below.

It is noticeable that the majority of states on the list are short on ‘democracy’ – Sarkissian may like to praise it, but he is open about valuing competence and technocracy in a very Blairite fashion. Singapore and Botswana are notional democracies in which the same party has ruled since independence; in addition Ireland has traditionally shared power between two parties which have been virtually indistinguishable in orientation (and against which he portrays Sinn Fein as ‘populist’).

Ireland is the prime example of the small state whose ‘success’ should be qualified. The transformation of a socially cohesive, conservative society into a country at the leading edge of hyper-liberalism and aggressive immigration. It is particularly stark when placed against the polar opposite approach of the UAE, which imports workers (intellectual and unskilled), on terms varying from attractive to contract-slavery, without the slightest thought of giving citizenship to any but the fewest and most valuable. Sarkissian’s idolatry of Ireland is somewhat misplaced, particularly given his generally pro-British career and stance: quoting the Economist, he endorses the view of Ireland as being a ‘diplomatic superpower’, which is quite unwarranted in my view, and is far from being a ‘middle power’ as he claims (that would surely be Israel, particularly given its nukes). Ireland has sold its soul to US-globalism, and the best you can say is that it got a decent price for it.

One theme that comes through about Sarkissian’s small states is that of non-alignment. From Switzerland’s legendary neutrality, to Ireland’s formal condolence to Germany on learning of Hitler’s death, the eras of the Cold War and the ‘unipolar moment’ after 1991 have suited this strategy. Even Israel, benefitting from the most unilateral special relationship imaginable, cooperates with China and Russia. Qatar has leveraged its position as the enfant terrible of the Gulf states to its success, from diplomatic isolation to hosting both the largest US base in the region and the leadership of Hamas. I believe this is changing – and this year’s bombing of Doha by Israel may be a sign of this.

Sarkissian’s potted histories of his choices are generally pretty good, particularly in the cases of the autocracies, from whose leaders he has learnt at first hand. There are interesting facts and observations along the way, such as the Jewish concept of bitachon: ‘A term that encompasses notions of security, assurance and guarantees… It encompasses not only a feeling of security but also the absence of potential threats.’1 In general, his message is that success is not generalisable. Being ‘smart’ is a mantra, not a recipe: it reminds me of a friend who wanted ‘to be a tycoon’. But his suggestion that small states form a ‘club’ is not a bad one: not because it will save the world, but as the world becomes less hospitable for them, it may help save themselves.

The British withdrawal from the Trucial States

1968 is one of those hinge years where important events coalesce, so much so that some things are easily missed. One such was the announcement on 16 January by the Wilson government that the British would withdraw its military presence east of Suez. The resulting round of decolonisation led to the creation of two of Sarkissian’s examples – Qatar (as well as Bahrain and Oman) and the federation of the Trucial States to form the United Arab Emirates.

Britain’s interest in Arabia was initially strategic: securing the passage to India. Aden had been acquired by the East India Company as a coaling station before the Suez Canal had even opened (Thomas Fletcher Waghorn had established an overland postal route in the 1830s, and steamers sailed from Suez to Calcutta from 1839). British interest in the Gulf was to protect trade between Persia and India from piracy. The emirates of the Trucial States came under British protection from 1820, and more formally from 1853’s Treaty of Perpetual Maritime Truce (hence the British name).

This was Empire at its lightest touch: control over foreign and defence policy without seeking to interfere with internal arrangements. The marginal life of the sheikhdoms, dependent on pearling for currency and dates grown in oases, attracted little interest before the oil boom. The tribes of the the Abu Dhabi desert were described by British Arabist Wilfred Thesiger as ‘among the most authentic of the Bedu, the least affected by the outside world’.2

Post-war decolonisation was the driven by a number of factors: anti-imperial pressure from the US, the financial cost of empire, and a deep-seated liberalism across the British establishment (which dominated both parties). It was the latter which drove the independence of the Trucials. The cost to Britain in defence was estimated at only £12 million per annum3; easily outweighed by the revenues earned from British interests in oil concessions (which subsequently soared). Half of Britain’s oil came from the Gulf. The sheikhs themselves had none of the drive to independence of the Arab revolutionary drive elsewhere, and even offered to cover the costs of keeping a military presence.

For once, the Americans in the dying days of the Johnson administration, and mired in Vietnam, wanted Britain to stay. ‘The U.S. Government continue to believe that the present British position in the Gulf is crucial to the stability of the area’ recorded a Foreign Office official.4 It was ideology, not financial or geopolitical pressure, that led to our exit from the Gulf – ideology which fed into a particular form of defeatism about the Trucials.

Some sense of defeatism was warranted after a three substantial setbacks: the nationalisation of the Anglo-Persian Oil Company by the Mossadegh government in 1951, the Suez crisis of 1956, and the embarrassing withdrawal from Aden in 1967. The 1968 independence movement was different. Mossadegh had been replaced in the CIA-backed coup, and the Arab nationalist movements inspired by Nasser which had driven the Aden insurgency were not present of the Gulf shore sheikhdoms, for which aggressive Arabism was a threat.

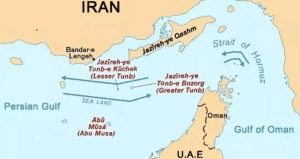

British encouragement for the Trucials to form what was to become the UAE was central. A wider federation had been contemplated, including Bahrain and Qatar, but the British favoured keeping them apart, for practical reasons rather than anything else – Bahrain being more ‘advanced’ than the others (and being the first to strike oil in 1931). Britain also intervened with Iran in the independence negotiations. Iran had claims over Bahrain, and three islands located in the Straits of Hormuz (Abu Musa and the two Tunbs islands) otherwise recognised as belonging to two of the Arab Emirates. Britain effectively brokered a ‘deal’: Iran ceded claims to Bahrain, but took Abu Musa and the Tunbs islands – the latter by force, in what can only be described as a co-ordinated move by Britain and Iran, the day before the 1971 withdrawal.

Arab righteous anger at the ‘betrayal’ seems a to have been a deliberate attempt to deflect the blame onto Britain, in the last hours when it was still responsible for the Trucials’ defence. And it was costly – not in terms of ‘influence’ but directly, as Libya nationalised BP’s interests in the country in response. The dispute over the Tunbs islands remains (formally) unresolved. It also provided an excuse for the sheikhdom claiming ownership, Ra’s al Khaimah, not to join the Union until the following year – in reality, until oil prospecting in its territory proved unviable.

Labour insisted on the necessity of defence cuts – in order not to introduce prescription chargers to their beloved NHS. Heath’s Conservatives, in 1968, had opposed the withdrawal from the Trucials, not (naturally) for the reasons of British interests, but rather a sense of ‘honour’ in not betraying loyal vassals. In office, the Heath government ignored the rump imperialist wing of the Tory party (it still existed in 1970) and pressed ahead with independence. Heath’s eyes were on Europe, not the Gulf.

The UAE, as constituted, has been remarkably successful, not just in exploiting its natural resources, but also in realising the need for wider economic development. It has been fortunate in the encouragement of Britain, and has remained an unwavering Western ally (in contrast to, say, Qatar). But it is absolutely fanciful to suggest, as does Sam Dalrymple, that the ‘official’ position of the Trucials before 1947 as part of the Indian empire could or should have led to their oil wealth accruing to the Subcontinent.5

The question, from a British perspective, is: as we essentially forced independence on the UAE, could we have got a better deal? Unlike other former concessions, Abu Dhabi (the largest oil producer) did not nationalise its interests wholly, but allowed foreign interests to retain 40%. The UAE has remained resolutely Western aligned, although the new federation within weeks declared its ‘total non-alignment’6. Nevertheless, it is hard not to think that, as ever, the decisions and debates, along with the interests of both major UK political parties, were motivated not by the interest of the British people, but by liberal ideology along with a Victorian hangover of propriety. It is telling that one of the few times that the Trucials were raised in Parliament was to ensure that they were no longer practising slavery.

Small States and Middle Powers

What are the lessons for Farage, the UK or Armenia?

The current geopolitical situation and the rise of the real multipolarity is changing the dynamics between the small and medium states. Simply put, multipolarity is favouring the Middle Powers (if they act wisely), but creating a much riskier world for small states.

The architecture of multipolarity is allowing Middle Powers to play more than once side simultaneously, as the great powers compete for influence, investment and profit. And it’s allowing them to take action, up to and including military intervention. The clearest example is Turkey, who have led the way for a long time: re-writing the politics of the south Caucasus, through its ‘little brother’ Azerbaijan’s conquest of Artsakh from 2020 to 2023; and combining with Israel (with the backing of the US) to intervene in Syria.

International relations specialist Sumantra Maitra paints Turkey here as a reviving empire:

Neo-Ottomanism isn’t just an academic debate anymore but a quantifiable policy platform, observable in its aspirations to regional hegemony by acquiring new proxies and protectorates, expanding regional influence, as well as the attempted normalisation of decades-old internal grievances with ethnic and religious minorities, such as Kurds and Armenians, in a style reminiscent of the Ottomans’ imperial cosmopolitanism…. The western realignment with Turkey, much to the dismay of Greeks, Israelis, and Cypriots, therefore, is once again simply a logical reaction to the threat of a revanchist Russian power in the east, and the need to incorporate a newly influential Turkey as a legitimate buffer in the European balance.

He’s right in attaching importance to the rise of neo-Ottomanism, but wrong in the details. There is no attempt to revive anything like ‘normalisation’ with Armenia; the realignment in the South Caucasus is a dripping economic and cultural takeover of a weakened rival (abetted by the western-backed Pashinyan regime in Yerevan) backed by military threats from Azerbaijan. And Erdogan can hardly be called a ‘buffer’ against Russia when he (and Azerbaijan) have consistently worked with Russia when it has suited them. The West has been quite consistent in its support for Turkey, it is rather that Turkey has seen increased opportunities to leverage its position.

It is not specific Russian revanchism which has allowed this; it is a pattern repeated across the Middle Powers. Pakistan is correctly described here as having had a ‘Year of Diplomatic Miracles’: from defence deals with Turkey and Malaysia, up to a full ‘Strategic Mutual Defense Agreement’ with Saudi Arabia (widely seen as a direct result of the Israeli attack on Qatar). US intervention in the brief conflict with India earlier this year leaned towards the weaker nation, whilst Pakistan claimed to have downed five Indian fighter planes with its Chinese-made jets. All while the country continues to be an economic basket case.

Or take Kazakhstan. The world’s largest uranium producer is assuming leadership of the Central Asian countries (the ‘Stans’), and successfully exploiting both the Great Powers and the other Middle Powers. Foreign Direct Investment in the country is heavily western (the largest being the Netherlands and the US, at 23.3% and 19.6% respectively, and the US boasts about deepening its relationship. Kazakhstan this year voted to build its first nuclear power plant, awarding the contract to Russia’s Rosatom, in a decision which was as much political as economic – China’s bid was lower but Russia processes its uranium.

Turkey and Pakistan illustrate how the positioning of a Middle Power has evolved from the Cold War through to multipolarity. Both initially sided closely with the West – Turkey with the US and NATO (becoming a member in 1952, and hosting US nuclear weapons since 1959); Pakistan with Britain and then the US. Turkey’s close relationship with its Great Power sponsors even allowed it to sponsor an effective breakaway Turkish state in northern Cyprus with impunity. Pakistan was ‘allowed’ to develop its own nuclear weapons. Pakistan is China’s biggest arms export market, and China is its largest investor; but the increasing dependence of the early 21st century has been balanced recently by Pakistan pursuing a more multi-track foreign policy. Similarly, Turkey initially sought greater integration with European markets, before both sides retreated to a more realistic policy of engagement at a distance, albeit with Turkish politics influencing Europe, rather than vice versa.

Middle Powers are working with their fellows when it suits, and at other times competing. Turkey and Israel combined at least tacitly in the overthrow of Assad in Syria – Israel signed a ‘ceasefire’ with Hezbollah on the very same day as Turkish-backed HTS forces moved on Aleppo. Israel then undertook a major air campaign to cripple Syria’s military capabilities and advance its position in the Golan Heights. Turkish rhetoric since the Gaza campaign started has been for public consumption: Turkey has kept Israel supplied with oil throughout, and Israeli-Azeri military co-operation has continued throughout. It remains to be seen whether the interests of expanding neo-Ottomanism and Greater Israel will clash in the future (as many, including Dr Maitra, foresee) or whether the co-operation will continue, if uneasily.

Eurasia, from the Middle East to Central Asia, is the home of the Middle Power, and the recent fate of Syria a conformation of how threatening the geopolitical scene is for Small States. Appeals to the ‘International Community’ or the ‘Rules-Based International Order’ have always been hollow covers for power, but this will become clearer. In the absence of the level of military spend afforded by an Israel or a UAE, the safest option would now appear to be for a Small State to get a Big Backer – that it can trust, as far as that is possible.

Armenia’s drive to the West is an attempt to do this, but even then, it is confused: is it looking to the US or the EU to be its principal protector? Will the EU even manage to achieve the Great Power status to which it aspires? And in either case, why would the interests of Armenia outweigh those of Turkey for either of them?

Sarkissian does not touch on these questions, or offer any solutions, beyond blaming previous governments. Having ushered in the Pashinyan government as President in 2018, he did call for the Prime Minister’s resignation after the 2020 war. Frustrated by his ceremonial role, he resigned the presidency in January 2022; but although he states that he ‘felt he could be more helpful as a civilian’, he has been a marginal figure in politics since then. This book is not going to help.

What about Farage, and the position of the UK in the multipolar world? According to my model, we should be well placed to act as a Middle Power. From this point of view, it is less relevant that Brexit has been subverted – independence from Europe would be able to be leveraged anyway. Britain should be in a position to work with all of the Great Powers – and the Middle Powers we choose – on our own terms; including Russia and China.

Of course, this is the direct opposite to the strategy across every part of the political and bureaucratic elites in whose vision the UK is protected by the junior place as the junior party in the Special Relationship, subservient to the EU for trade matters, and subject to polite world opinion. Farage and Reform offer nothing to combat this. And if it seems demeaning to emulate something of the strategy of Turkey, remember that in terms of purchasing power parity, our GDP is only just ahead.

Rachel Reeves Budget-day publicity centered around the embarrassing photo reproduced above. It was an unfortunate metaphor for the country’s finances, but is also one for our geopolitical position. Rather than Brzezinski’s Grand Chessboard, we are trapped in Reeves’ Empty Chessboard, where we don’t even set our pieces to play.

Armen Sarkissian, ‘The Small States Club: How Small Smart States Can Save The World’ (C. Hurst & Co, 2023), pp108 -109

Quoted in Frauke Heard-Bey, ‘From Trucial States to United Arab Emirates’ (Motivate Publishing, 1982,2004), p 41

Wm. Roger Louis, ‘The End of the British Empire in the Middle East, 1952 – 1971’ (OUP, 2025), p 385

Quoted in Louis, p 387

He accuses Britain of ‘negligence’ and ‘abandonment’. See Sam Dalrymple, ‘Shattered Lands: Five Partitions and the Making of Modern India’ (William Collins, 2025), p 303. My review of his fanciful and over-lauded tome is here

This article (The Empty Chessboard) was created and published by Mat and is republished here under “Fair Use”

••••

The Liberty Beacon Project is now expanding at a near exponential rate, and for this we are grateful and excited! But we must also be practical. For 7 years we have not asked for any donations, and have built this project with our own funds as we grew. We are now experiencing ever increasing growing pains due to the large number of websites and projects we represent. So we have just installed donation buttons on our websites and ask that you consider this when you visit them. Nothing is too small. We thank you for all your support and your considerations … (TLB)

••••

Comment Policy: As a privately owned web site, we reserve the right to remove comments that contain spam, advertising, vulgarity, threats of violence, racism, or personal/abusive attacks on other users. This also applies to trolling, the use of more than one alias, or just intentional mischief. Enforcement of this policy is at the discretion of this websites administrators. Repeat offenders may be blocked or permanently banned without prior warning.

••••

Disclaimer: TLB websites contain copyrighted material the use of which has not always been specifically authorized by the copyright owner. We are making such material available to our readers under the provisions of “fair use” in an effort to advance a better understanding of political, health, economic and social issues. The material on this site is distributed without profit to those who have expressed a prior interest in receiving it for research and educational purposes. If you wish to use copyrighted material for purposes other than “fair use” you must request permission from the copyright owner.

••••

Disclaimer: The information and opinions shared are for informational purposes only including, but not limited to, text, graphics, images and other material are not intended as medical advice or instruction. Nothing mentioned is intended to be a substitute for professional medical advice, diagnosis or treatment.

Disclaimer: The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of The Liberty Beacon Project.

Leave a Reply