JOHN REDWOOD

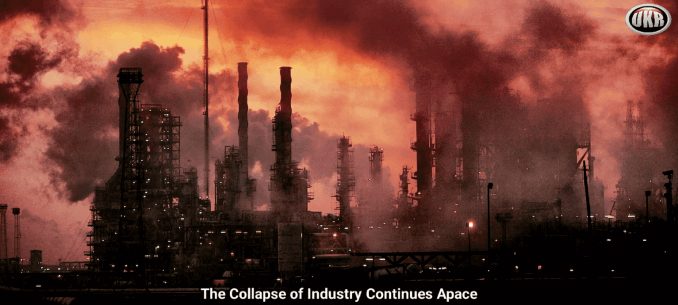

Whilst Labour MPs were undermining their government over its clumsy welfare cuts, another UK refinery went bankrupt.

A hand wringing Labour Minister blamed the management and promised to get involved in either finding a new owner who thinks they could turn a profit, or looking at some other use for the site. This latter offer implies acceptance that 440 good industrial jobs will go as the refinery closes. The Minister claimed credit for a government meeting with the industry prior to this collapse. Clearly the likely meeting messages from the industry about high energy costs were ignored by a government determined to deindustrialise us to hit unrealistic carbon targets.

The predictable collapse of refineries, ceramics, vehicle manufacture, petrochemicals and other energy dependent industries is proceeding apace. The government sheds crocodike tears and blames others. The prime cause is sky high energy prices. The main cause of them is the high taxes and subsidies needed to supercharge decarbonisation. It makes us hopelessly uncompetitive. It also adds to world CO 2 in a cruel irony of total policy failure.

SOURCE: John Redwood’s Diary

See Related Articles Below

Labour has no answers to Britain’s economic slump

The government’s long-awaited industrial strategy is a weak rehash of familiar, failed ideas.

PHIL MULLAN

The Labour government finally launched its long-awaited industrial strategy last week. Given the chaos and u-turns of his first year in office, it was a wonder UK prime minister Keir Starmer managed to keep a straight face when claiming that his 10-year economic plan provides ‘stability’ and ‘certainty’ for business.

The contents of the industrial strategy are remarkably similar to the other supposedly ‘bold’ industrial-policy documents and growth plans announced by successive governments in the decade-and-a-half since the financial crisis. The two flagship proposals this time – cheaper energy and improving skills – featured strongly in all previous industrial strategies. Starmer’s other commitments are just as familiar. These include promises to lighten regulatory burdens; a repeat of announcements to (inadequately) fund public research and development; and the rebranding of ‘freeports’ and ‘investment zones’ as ‘industrial-strategy zones’. Given the amount of regurgitation going on, it’s tempting to think the government is now using AI to draft its policies.

Why did it take nearly 12 months for the government to produce such a humdrum industrial strategy? This strategy is supposed to be a ‘central part’ of Labour’s ‘growth mission’, so why has there been so little urgency?

The delay speaks to an all too familiar problem – the desire of countless British governments to kick the can down the road. Procrastination has been a feature of our technocratic administrations since the 1990s. Their guiding managerial impulse is to avoid or at least put off making any decision that might be disruptive to the status quo. Labour’s dithering was probably further aggravated by the faint and now extinguished hope that chancellor Rachel Reeves might find the odd billion pounds or so to add some welly to these otherwise run-of-the-mill industrial policies.

That this has not happened has left Labour’s policy proposals looking anaemic. Take the measure that Labour promoted most last week – the slashing of electricity prices for business. This sounds like great news, given British businesses endure much higher electricity prices than their rivals in any other major developed country.

But the detail of the policy tells a rather less promising story. It suggests the government could subsidise energy prices for just 7,000 electricity-intensive manufacturers. The government itself admits that these manufacturers only support about 300,000 skilled jobs – that’s just one per cent of Britain’s total workforce. Furthermore, the policy will not come into effect any time soon. There will be another two years’ worth of ‘consultation’ to decide which companies ought to be eligible for the scheme, with a ‘review point in 2030’.

The real kicker is that the subsidies will not be coming out of the existing tax take. Instead, they will be funded through vague ‘reforms to the energy system’ and, crucially, ‘additional funds from the strengthening of UK carbon pricing’. This implies that a few thousand businesses will have their electricity prices subsidised by higher carbon prices for at least some of the millions of other businesses in the country.

The hackneyed policies contained in Labour’s strategy seem wholly inadequate given the scale and depth of Britain’s economic problems. Indeed, the government’s own green paper on industry from last October did not hold back on the extent of the UK’s economic malaise. It pointed out the persistently low levels of investment in British businesses, which are ‘routinely ranked in the bottom 10 per cent of OECD countries for overall investment’. It also noted that, while Britain’s research institutes are still pretty good at invention, the capacity to commercialise and roll out innovation across businesses remains poor.

Above all, the green paper drew attention to ‘the fundamental and longer-term challenge’ facing the British economy – namely, ‘a slowdown in productivity growth over the past decade and a half, which is the ultimate driver of people’s living standards’. It said that the productivity slump is driven by slowing market dynamism, a problem generated by the fact that labour and capital have generally stopped moving from less productive firms to more productive ones. This long-term decline in Britain’s business dynamism is, it said, the most important drag on productivity growth.

Any new industrial strategy, the paper concluded, would need to increase dynamism by allowing labour and capital to flow more freely towards growth-driving sectors. This will be disruptive and will create ‘losers’, as it will lead to the closure of failing businesses. As the green paper argued, the government will therefore need to consider these impacts and provide the right transition mechanisms to ensure that people are not ‘left behind’.

Yet, in last week’s long-awaited industrial strategy, the insights from October’s paper had been ignored. It talks of the need to create the next generation of challenger companies. But it says nothing about how to allow capital and labour to move towards the new, more productive companies – namely, by letting today’s unproductive businesses fold. It is also silent on the state’s responsibility to support people while they move from the declining and folding businesses into the better jobs provided by the challenger companies.

This industrial strategy is all too typical of our political elites’ approach to governance. They are ensnared in the present and remain committed to sustaining and supporting the status quo. The government’s advisers may have tried to draw Labour’s attention to the vital importance of energising business dynamism. But today’s managerial political class lacks the honesty and courage to do what needs to be done.

None of this is a surprise. Successive governments have churned out equally disingenuous and ineffective industrial strategies. Which raises the question: why there is so much political and even public support for the idea of an industrial strategy in the first place?

After all, even ministers acknowledge that the British state is dysfunctional. State bodies have run down public infrastructure, proven incapable of providing basic services and have seemingly lost control of our borders. The litany of state failures goes on and on. So why, given this awful record, do even anti-establishment parties like Reform UK continue to support active state intervention in industry?

The answer, I think, derives in large part from nostalgia. This is not a yearning for the revival of heavy industry itself. Politicians and much of the public don’t actually want a return to arduous and dangerous work down mines or in steelworks. Rather, they yearn for the culture and values of the industrial era, before the ravages of deindustrialisation kicked in under Margaret Thatcher during the 1980s. They yearn, that is, for a time when there was still a sense of community and solidarity. For a time when hard work was valued and people took civic pride in their locales. For a time when people assumed that their children’s generation would have better lives than they had.

The allure of industrial strategies rests therefore on the cultural attraction of the industrial era. It’s entirely understandable. But right now we need so much more than yet another spirit-raising but ultimately ineffective industrial strategy.

Britain’s economic renewal depends on regaining collective belief in our ability, as a society, to forge a better future. Only then will we be able to endure the disruptions needed to bring about meaningful economic and social transformation. Given that the political class is terrified of change, it will be up to the people to seize the day.

Phil Mullan’s Beyond Confrontation: Globalists, Nationalists and Their Discontents is published by Emerald Publishing. Order it from Amazon (UK)

This article (Labour has no answers to Britain’s economic slump) was created and published by Spiked Online and is republished here under “Fair Use” with attribution to the author Phil Mullan

*****

Net zero: unrealised fragility

RICHARD NORTH

In passing, I can’t help but note the Guardian applauding the passage of the pride parade in Budapest as a “triumph for European values”.

Perhaps it’s my addled brain, still stewing in the heat of a summer’s day, but I couldn’t escape what I saw as the irony of the BBC running at the same time a news item on Stephen Ireland who co-founded Pride in Surrey in 2018, who has been jailed for 24 years for raping an “extremely vulnerable” 12-year-old boy”. There’s not a lot of talk of “European values” there.

Meanwhile, the behaviour of an uppity half-caste at Glastonbury continues to dominate the headlines, as the police launch a criminal investigation into him and the performance of another group which goes by the unlikely name of “Kneecap”. The role of the BBC director general, Tim Davie, is also keeping the hacks entertained both in The Times and the Telegraph.

For my part, though, I have said as much as I need to for the moment. While the interest peaks at the level of obsession, the real world is struggling to intrude, with the latest effects of the government’s net-zero policy becoming apparent.

Over the years, I have written a great deal about this and the closely allied issue of energy policy, but less so of late as there seems little point in repeating myself. Basically, the net-zero policy is baked into the system and under the malign tutelage of Ed Miliband is set to deindustrialise Britain and wreck the economy more thoroughly than Rachel from accounts.

However, yesterday’s news of the collapse of the Lindsey Oil Refinery demands attention. The plant is situated in North Killingholme, in the district of North Lincolnshire, currently owned and operated by the Prax Group, a company led by Winston Sanjeev Kumar Soosaipillai, who bought the refinery from the oil giant Total in 2021 for around $168million.

The operation, which processed about 96,000 barrels of oil a day in 2024, filed for insolvency over the weekend and a winding up order was made yesterday against the site operator,

At a strategic level, this is bad news. After the closure of the Grangemouth facility in April of this year – Scotland’s only oil refinery – this means that there are only four refineries left in the UK. They do not have the volume to meet the whole of the national demand, leaving the Uk dangerously dependent on imports.

But this isn’t an ordinary net-zero disaster. The Prax Group is the trading name for Soosaipillai’s umbrella company, State Oil Ltd, other assets of which are affected, although subsidiaries involved in wholesale operations, Prax Petroleum, Harvest Energy and Harvest Energy Aviation, remain outside the insolvency.

Since its acquisition by Prax, the government says Lindsey has lost about £75mn, but the company had been “unable” to answer questions from the government about its finances. Given the strategic importance of the plant, Downing Street has taken a direct interest in the liquidation and says “workers have been badly let down” by Lindsey’s owners.

Business secretary Jonathan Reynolds has written to the Insolvency Service to demand “an immediate investigation into the conduct of directors and the circumstances surrounding this insolvency, while a spokesman for Starmer complains that the company had “left the government with very little time to act”.

But behind the scenes is a story which has yet fully to emerge. Prax was founded in 1999 by its chief executive and chair, a Shri-Lankan-born accountant, Winston Sanjeev Kumar Soosaipillai with a single petrol station near St Albans.

State Oil Limited emerged a year later and it has since grown into a sprawling conglomerate including refineries in the UK and South Africa, a network of petrol stations and a trading business, with an annual revenue which is now claimed to be £8 billion.

In June 2023, the company acquired Hurricane Energy an exploration and production company operating in the waters to the west of the Shetlands, for the sum of £249 million, and it is by no means clear whether this operation has also gone into liquidation.

Back in October 2017, the Sunday Times published a profile of Soosaipillai and his wife Arani, who is co-owner and plays an active role in the management of the company.

In just over a decade, the paper remarked then, State Oil had grown from a £15m turnover minnow into one of Britain’s biggest importers and suppliers of petrol and diesel, with a turnover of $2.3bn (£1.7bn). It had snapped up oil terminals in northeast England and south Wales, and a supply business called Harvest Energy – giving it a network of about 200 franchised petrol stations.

Yet for all this stellar growth, the paper observed, Prax is shrouded in mystery. Industry insiders questioned how the company, owned by two reclusive founders, had done it.

The first few years of Prax’s existence, the paper says, were humdrum. It bought a couple of service stations in Sussex and the Midlands, but trading was so insignificant that it was not obliged to file full accounts.

In 2009, all that changed. A new director, Don Camillo Emilio Borneo, joined and sales took off. Turnover of £75 million in 2008 had swollen sevenfold by 2012. In early 2015, the company did a deal that sent sales soaring above £2 billion, paying $22.6 million for Harvest Energy and Harvest Aviation in a debt-backed transaction.

Harvest had been sold to Prax by one of Ireland’s richest men, Denis O’Brien, and Trafigura, the Singapore oil trading giant found guilty of dumping toxic waste in Ivory Coast. Harvest then had about 90, mainly franchised, petrol stations.

Currently, Soosaipillai’s family is said to own 100 percent of the group, yet almost nothing is known of the couple who run it. No photographs of the couple appear to exist on the internet. Oil veterans say they do not attend industry events, and they have never given an interview.

Yet, even then, Prax was seen as big player with big ambitions, claiming to supply 10-15 percent of the UK’s road fuel, with trading offices in Switzerland, Texas and Singapore.

It was said to make very slender margins, which was not regarded as unusual for fuel suppliers, but that had left some in the industry bemused about its “blockbuster” rise. Rivals argued that it undercut them to win market share, while a veteran industry adviser said: “There are a lot of people in the sector who ask a lot of questions about Prax. Nobody has ever come up with any definitive answers”.

And answers currently there are none. The Financial Times says the refinery had been struggling commercially for some time, but rather than run it as a standalone company, Soosaipillai had tended to use cross-group guarantees to help finance its operations, leaving other parts of the company exposed to the insolvency process.

According to Unite, Britain’s largest trade union, the UK oil and gas industry had been placed on a “cliff edge” by policies aimed at cutting carbon emissions – i.e., net-zero – with the inference that this is what has driven Prax to the wall.

And therein lies the rub. Ed Miliband needs to ensure that the remnants of the industry on which we so much rely has a sound financial base. Yet here we have critical infrastructure in the hands of private individuals of foreign extraction, an empire with very little obvious substance, from which they can walk away when the going gets tough.

The government is for the moment, taking charge of the running of the plant and the administrator is exploring a potential sale of parts of the wider group that remain outside administration proceedings, such as its roughly 200 petrol stations in the UK and the hundreds more it operates across Europe.

But the energy system is fragile enough without this, and without us even knowing, it has been far more fragile than anyone realised. It makes one think what further horrors are in store for us, before the economy finally grinds to a halt.

••••

The Liberty Beacon Project is now expanding at a near exponential rate, and for this we are grateful and excited! But we must also be practical. For 7 years we have not asked for any donations, and have built this project with our own funds as we grew. We are now experiencing ever increasing growing pains due to the large number of websites and projects we represent. So we have just installed donation buttons on our websites and ask that you consider this when you visit them. Nothing is too small. We thank you for all your support and your considerations … (TLB)

••••

Comment Policy: As a privately owned web site, we reserve the right to remove comments that contain spam, advertising, vulgarity, threats of violence, racism, or personal/abusive attacks on other users. This also applies to trolling, the use of more than one alias, or just intentional mischief. Enforcement of this policy is at the discretion of this websites administrators. Repeat offenders may be blocked or permanently banned without prior warning.

••••

Disclaimer: TLB websites contain copyrighted material the use of which has not always been specifically authorized by the copyright owner. We are making such material available to our readers under the provisions of “fair use” in an effort to advance a better understanding of political, health, economic and social issues. The material on this site is distributed without profit to those who have expressed a prior interest in receiving it for research and educational purposes. If you wish to use copyrighted material for purposes other than “fair use” you must request permission from the copyright owner.

••••

Disclaimer: The information and opinions shared are for informational purposes only including, but not limited to, text, graphics, images and other material are not intended as medical advice or instruction. Nothing mentioned is intended to be a substitute for professional medical advice, diagnosis or treatment.

Disclaimer: The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of The Liberty Beacon Project.

Leave a Reply