How Marx Provided the Blueprint for Central Banking Control

ESCAPE KEY

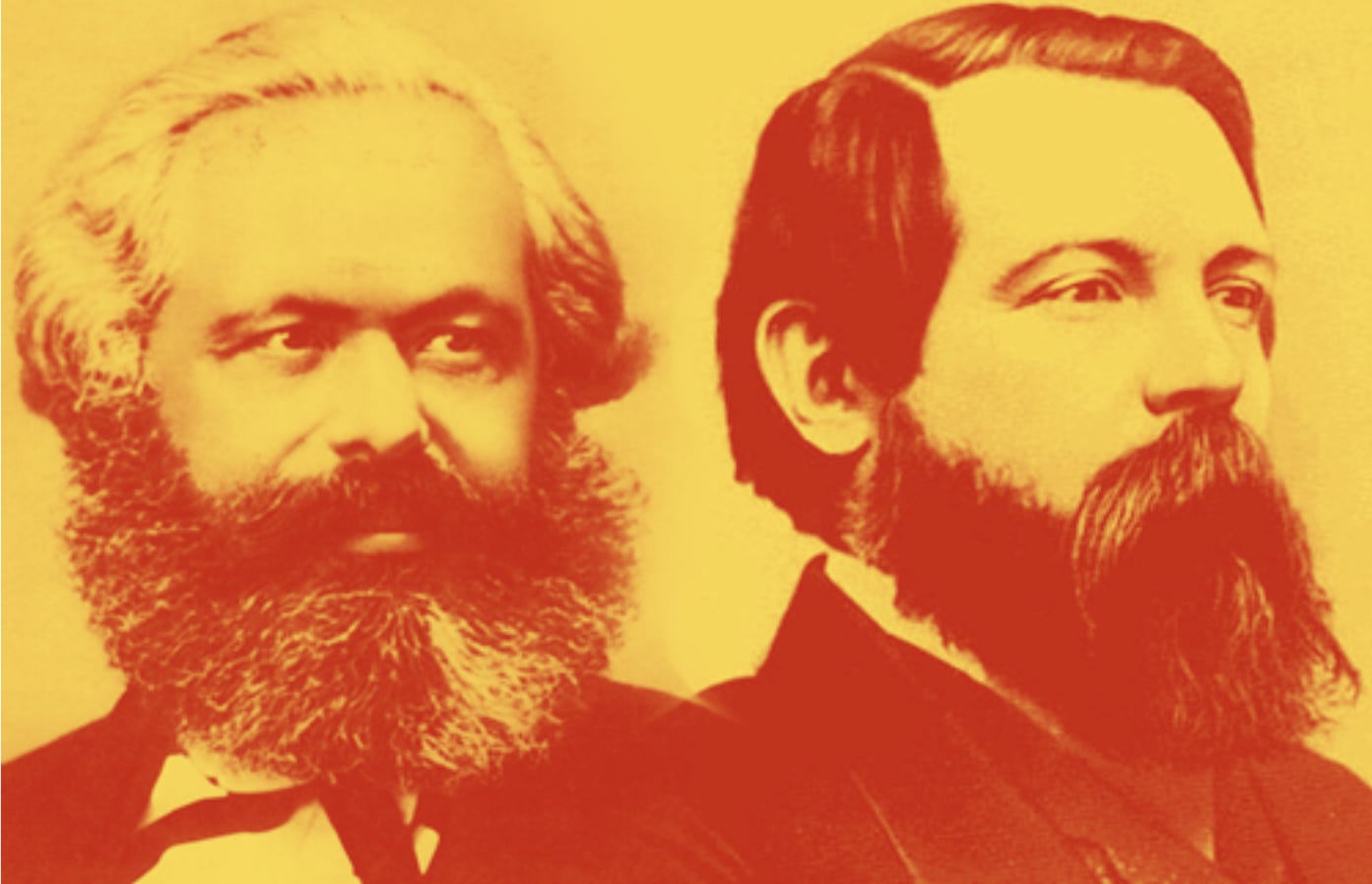

When Marx and Engels laid out their famous 10 planks in the Communist Manifesto, they told you they imagined a world where workers would seize control of the means of production.

But what if I told you that these same 10 planks — when filtered through a technocratic lens — describe almost exactly the world we live in today?

Far from being a revolutionary charter, the Communist Manifesto function as a blueprint for systemic centralisation. The only thing that changed was who got to wield the centralised apparatus.

The twist is that rather than workers controlling the system in contemporary society, it’s the algorithm architects, the data scientists, and the platform builders who’ve ended up in charge. We got centralised control and resource redistribution — just not quite the kind anyone expected.

This isn’t a coincidence. But it’s probably less likely that central banks later figured out how to implement Marx’s system, and more likely that Marx was developing theoretical frameworks on behalf of central banking interests from the beginning.

David Ricardo helped establish central banking currency monopoly with the Bank Charter Act of 1844. Four years later, Marx publishes the Communist Manifesto, explicitly citing Ricardo’s labour theory of value as foundational to his analysis. Marx was building on theoretical frameworks that were already connected to central banking interests.

Marx may have been the intellectual front for central banking interests, developing the theoretical justification for centralised control that they wanted to implement.

Let’s walk through each plank and see how Marx provided the intellectual framework for the centralised monetary control system that central banks would later implement through technological interfaces.

The 10 Planks, Technocratically Inverted

- Abolition of property in land and application of all rents of land to public purposes

- Marx wanted: Democratic collective ownership where workers control land use decisions.

- Technocratic inversion: Natural capital accounting and ESG land metrics. Zoning laws increasingly rely on environmental data models, urban planning is driven by carbon algorithms, and platforms like Airbnb have effectively created a parallel system of land use that bypasses traditional ownership. This isn’t just anecdotal — it’s institutionalised planetary stewardship where your property rights matter less than algorithmic determinations of ecological optimisation.

We got centralised land control, but instead of worker collectives making democratic decisions about land use, algorithms make optimisation decisions. Same structural outcome (centralised control), opposite control mechanism (algorithmic vs. democratic).

- A heavy progressive or graduated income tax

- Marx wanted: Democratic political control over wealth redistribution through transparent taxation.

- Technocratic inversion: Monetary policy redistribution. Quantitative easing, interest rate manipulation, and inflation policy redistribute wealth automatically. Asset price inflation benefits those who own assets, whilst wage earners lose purchasing power. Central banks achieve massive wealth redistribution through monetary policy, whilst algorithmic pricing systems implement the micro-level adjustments. The tax happens through currency debasement rather than explicit collection. Meanwhile, OECD and IMF global tax harmonisation initiatives coordinate this redistribution at the planetary level — algorithmic taxation isn’t just monetary policy, it’s global clearinghouse policy.

We got massive wealth redistribution, but instead of democratic political decisions about taxation, central bankers make monetary policy decisions that redistribute wealth invisibly. Same outcome (redistribution), inverted mechanism (hidden monetary vs. transparent political).

- Abolition of all rights of inheritance

- Marx wanted: Democratic elimination of dynastic wealth to ensure genuine equality of opportunity.

- Technocratic inversion: Algorithmic succession systems, though dynastic wealth persists at the top. Social mobility increasingly depends on algorithmic assessments: standardised test scores, LinkedIn profiles, and recommendation algorithms determine opportunities more than family connections for most people. The old money families maintain their position, but opportunity and access for everyone else are increasingly gated by algorithmic filters that determine who gets into which schools, jobs, and social networks.

We got the elimination of inheritance for most people, but instead of democratic equality, we have algorithmic filtering that preserves elite dynasties whilst subjecting everyone else to merit-based sorting. Same effect (reduced inheritance), inverted outcome (preserves rather than eliminates elite control).

- Confiscation of the property of all emigrants and rebels

- Marx wanted: Democratic worker control over assets of those who oppose the revolution.

- Technocratic inversion: Efficiency audits and deplatforming. Step out of line with platform policies, and your digital assets vanish. Get flagged by an algorithm, and your access to financial services disappears. The ‘confiscation‘ happens automatically when systems determine you’re not optimally compliant.

We got automated confiscation of non-compliant individuals’ assets, but instead of democratic worker decisions about who opposes the revolution, algorithms determine compliance. Same mechanism (asset confiscation), inverted control (algorithmic vs. democratic judgement).

- Centralisation of credit in the hands of the state

- Marx wanted: Democratic worker control over credit allocation for social priorities.

- Technocratic inversion: Central banking system control. The Federal Reserve, ECB, and other central banks control credit creation, whilst tech platforms provide the user interface. PayPal, Apple Pay, and digital wallets are just the front-end for a monetary system where central banks ultimately determine who gets credit and at what cost. Interest rates set by central bankers ripple through every algorithmic credit decision. But central banks are poised to retake direct control through CBDCs, fusing public and private power into a planetary financial clearinghouse.

We got centralised credit control, but instead of democratic worker priorities determining allocation, central banker priorities do. Same structure (centralised credit), inverted control mechanism (monetary authority vs. worker democracy).

- Centralisation of the means of communication and transport

- Marx wanted: Democratic worker control over information flow and logistics.

- Technocratic inversion: A handful of platforms control most communication (Meta, Google, Apple), whilst ride-sharing algorithms control transportation in most cities. The ‘state‘ control Marx imagined happened, but through private platforms that feel like public utilities.

We got centralised communication and transport control, but instead of worker collectives democratically managing information and logistics, algorithmic systems optimise for engagement and efficiency. Same structure (centralisation), inverted priorities (optimisation vs. democratic values).

- Extension of factories and instruments of production owned by the State

- Marx wanted: Democratic worker ownership and control of production facilities.

- Technocratic inversion: Amazon’s fulfilment centres, Google’s server farms, and Tesla’s Gigafactories operate like state-owned enterprises but with algorithmic efficiency. These aren’t owned by workers or traditional government — they’re controlled by whoever controls the optimisation algorithms.

We got centralised production control, but instead of workers democratically managing factories, algorithms optimise production. Same outcome (centralised production), inverted control (algorithmic vs. worker management).

- Equal liability of all to work

- Marx wanted: Democratic assignment of labour based on social need and individual capacity.

- Technocratic inversion: The ‘gig economy‘. Everyone’s expected to optimise their labour through platforms: Uber, TaskRabbit, Fiverr, LinkedIn. The industrial armies Marx imagined exist — they’re just mediated through apps that assign work based on algorithmic matching.

We got universal work obligation, but instead of democratic communities assigning work based on social priorities, algorithms match labour for platform optimisation. Same structure (universal work), inverted mechanism (algorithmic vs. democratic assignment).

- Combination of agriculture with manufacturing industries

- Marx wanted: Democratic integration of rural and urban production under worker control.

- Technocratic inversion: Smart cities and vertical farming, controlled by IoT sensors and agricultural algorithms. Rural and urban spaces are being integrated through logistics networks and automated systems that optimise resource flows across geographic boundaries.

We got integrated agriculture and manufacturing, but instead of worker cooperatives democratically coordinating production, algorithmic systems optimise for efficiency metrics. Same integration, inverted control (algorithmic vs. democratic coordination).

- Free education for all children in public schools

- Marx wanted: Democratic education to develop critical consciousness and worker solidarity.

- Technocratic inversion: Universal education, but now it’s increasingly about ‘competency streaming‘ — standardised testing, personalised learning algorithms, and skill-matching systems that sort human capital for maximum economic efficiency rather than human development. Education is no longer about forming citizens who can think critically and participate in democratic society, but about optimising inputs for the data economy.

We got universal education, but instead of developing democratic consciousness, it develops algorithmic compliance. Same structure (universal schooling), inverted purpose (optimisation vs. liberation).

The Perfect Alignment

We’ve achieved almost every one of Marx’s planks. Not as future possibilities, but as code already running. We did build the centralised system — but the workers don’t control it. The algorithms do.

- Plank 1 runs in code: Natural capital accounting dashboards, ESG land metrics, and carbon tracking systems determine land use more than ownership papers.

- Plank 2 runs in code: OECD global tax harmonisation frameworks, automated tax information exchange systems, and algorithmic redistribution through monetary policy.

- Plank 5 runs in code: BIS coordination protocols, CBDC pilot programmes, and real-time payment rails that central banks control.

- Plank 10 runs in code: AI-personalised education pathways, competency-based progression algorithms, and skills-matching systems that sort human capital.

This isn’t theoretical. The centralised control Marx envisioned exists right now, exercised through whoever controls the recommendation engines, the pricing algorithms, the credit scoring systems, and the platform policies that increasingly govern daily life.

Think about your last week. How many of your decisions were influenced by algorithmic recommendations? What you watched, where you went, what you bought, who you talked to, what job opportunities you saw. All increasingly mediated by systems optimised for engagement and efficiency rather than human autonomy.

Marx foresaw the withering away of the state, and in a sense it’s happening. But it hasn’t dissolved into worker self-rule — it’s been outsourced into algorithms, standards, and protocols. These systems of metrics feel neutral, even scientific, yet they function as law more coercive than legislation. Political institutions fade into ritual while the real governance is executed invisibly, through code and compliance engines that no citizen ever voted on.

The revolution isn’t coming — it’s already here, running in production environments across the planet.

The Monetary Foundation

At the root, every one of Marx’s planks only functions because it passes through the medium of exchange. Inheritance reform is enforced through financial instruments, education is rationed by funding mechanisms, transport and communication are mediated by platformised credit flows. Credit, taxation, land use, labour assignment — all are implemented today through clearinghouse logic. The continuity isn’t just structural; it’s monetary. The planks run in code because money itself has become programmable.

Every single one of these technocratic inversions depends on one fundamental power — control over the unit of account itself.

Money.

All the algorithmic resource allocation, platform controls, and digital asset management only work because they operate through monetary systems that central banks ultimately control. The ‘technocratic class‘ in Silicon Valley isn’t actually running this system — they’re implementing it on behalf of whoever controls money creation and monetary policy.

Central banks figured out that you don’t need to own the means of production if you control the medium of exchange. Fiat currency functions as the universal clearinghouse of the double coincidence of wants — every transaction, every trade, every exchange of value must ultimately pass through it. But to make that system global, all national currencies first had to be tied to a singular instrument: gold. The gold standard provided the clearinghouse architecture for merging currencies into one coherent system. Once that foundation was secured, the gold peg could be lifted, leaving fiat as the programmable infrastructure of centralised control. And that, incidentally, is precisely what happened.

You don’t need to seize factories if you can control credit creation, and you don’t need political revolution if you can implement systematic control through monetary policy and digital payment systems.

The Federal Reserve, European Central Bank, Bank of Japan — these institutions realised they could achieve Marx’s centralised control through interest rates, quantitative easing, and digital currency systems rather than through political struggle.

Tech platforms are just the user interface for monetary control.

Corporations may look like the dominant actors, but their behaviour is almost entirely shaped by the incentive structures set by central banks. Stock buybacks, mergers, cheap debt, global expansion — all of it flows from the cost of credit and liquidity provision dictated at the monetary level.

When the Fed, ECB, or BIS adjust rates, expand balance sheets, or trial new instruments like CBDCs, corporations simply respond to those signals. The real command authority rests not in Silicon Valley boardrooms but in the clearinghouses of central banking, where the incentives that govern corporate strategy are programmed.

The Commissioned Blueprint

The uncomfortable truth is that Marx and Engels were not merely independent philosophers developing theories in isolation. They were, in a very real sense, hired. The Communist League (formerly the League of the Just), through agents like Joseph Moll, Karl Schapper, and Heinrich Bauer, commissioned the Manifesto to articulate their revolutionary platform. They got exactly what they paid for: a powerful, compelling call to arms for the working class.

Yet, the client — a revolutionary workers’ organisation — is not the ultimate beneficiary of the intellectual framework they commissioned. The League wanted a weapon for liberation. Marx provided a blueprint for total systemic control.

The Communist Manifesto reads like a precise plan for centralised control because that is exactly what it is. It provided the intellectual justification and the structural roadmap for the consolidation of economic and social power. The great inversion is that this blueprint was not implemented by the proletariat but by the emerging technocratic and financial elite.

Marx built his system on the intellectual foundation of Ricardo — the very architect of the centralised monetary monopoly in Britain. Likely not a coincidence, but a capture of the intellectual spectrum. The ruling class of the 19th century didn’t just control capital; it funded the economic and philosophical theories that would legitimise the next phase of its power.

The ‘revolution‘ was never truly about putting workers in control. It was about creating a theoretical framework that would dismantle old, distributed forms of power (landed aristocracy, local credit) and justify their reconstitution under a new, centralised authority. Marx provided the most radical and logically rigorous version of this argument. The workers were the rhetorical vehicle, but centralisation was always the logical endpoint.

The absence of any serious framework for what comes after the so-called ‘dictatorship of the proletariat’ is revealing. Marx could describe the dismantling of distributed authority in great detail, but when it came to the practical mechanics of genuine worker self-rule, the blueprint went silent. That silence wasn’t an oversight; it was the clearest evidence that the endgame was centralisation itself. The revolution was never designed to decentralise power, only to install new custodians.

Central bankers and technocrats didn’t later co-opt Marx’s system. They simply implemented the half of the blueprint that served them: the centralisation of credit, the abolition of tangible property, and the systematic management of society. They skipped the part about democratic worker control and instead perfected control through the ultimate neutral, ‘scientific‘ authority: the algorithm.

Silicon Valley didn’t independently recreate the Communist Manifesto. They built the technological user interface for the centralised control system that Marx’s commissioned blueprint justified 180 years ago. The platforms, the algorithms, the ESG metrics, and the CBDCs are simply the 21st-century tools for achieving the 19th-century goal of total coordination.

This is why traditional politics feels irrelevant. The real revolution happened not in the streets in 1917, but in the meeting rooms of the Communist League in 1847 when they commissioned a document, and in the halls of Parliament in 1844 when they passed the Bank Charter Act. These were two fronts of the same war: the war against distributed, human-scale agency.

This article (Technocratic Inversion) was created and published by Escape Key and is republished here under “Fair Use”

••••

The Liberty Beacon Project is now expanding at a near exponential rate, and for this we are grateful and excited! But we must also be practical. For 7 years we have not asked for any donations, and have built this project with our own funds as we grew. We are now experiencing ever increasing growing pains due to the large number of websites and projects we represent. So we have just installed donation buttons on our websites and ask that you consider this when you visit them. Nothing is too small. We thank you for all your support and your considerations … (TLB)

••••

Comment Policy: As a privately owned web site, we reserve the right to remove comments that contain spam, advertising, vulgarity, threats of violence, racism, or personal/abusive attacks on other users. This also applies to trolling, the use of more than one alias, or just intentional mischief. Enforcement of this policy is at the discretion of this websites administrators. Repeat offenders may be blocked or permanently banned without prior warning.

••••

Disclaimer: TLB websites contain copyrighted material the use of which has not always been specifically authorized by the copyright owner. We are making such material available to our readers under the provisions of “fair use” in an effort to advance a better understanding of political, health, economic and social issues. The material on this site is distributed without profit to those who have expressed a prior interest in receiving it for research and educational purposes. If you wish to use copyrighted material for purposes other than “fair use” you must request permission from the copyright owner.

••••

Disclaimer: The information and opinions shared are for informational purposes only including, but not limited to, text, graphics, images and other material are not intended as medical advice or instruction. Nothing mentioned is intended to be a substitute for professional medical advice, diagnosis or treatment.

Disclaimer: The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of The Liberty Beacon Project.

Leave a Reply