Sex education in schools: part one

Sex education in schools has gone wrong

NEIL O’BRIEN

Many people will remember sex education in school with a cringe.

But sex education in schools today is more than cringe. We’ve drifted into a position where there are too many examples of sex education which, instead of providing neutral information, promotes, pushes and celebrates a set of ideas with bad real-world consequences.

While there is perfectly good sex and relationships education happening in many schools, there is too much that is not.

Take just one idea to start with.

In recent years sex education in many schools has deliberately told kids that they may have somehow been “born in the wrong body”. In so doing, schools have amplified and given official confirmation to bad ideas that kids are exposed to on social media.

What has been the result of encouraging such ideas? In 2009 the NHS’s gender identity development service (Gids) saw fewer than 50 children a year. By 2021-22 it was more than 5,000.

The number of children in England with a diagnosis of gender dysphoria by a GP rose fiftyfold over 10 years, between 2011 and 2021. According to one study, around 5% were given puberty blockers and around 8% were prescribed masculinising/feminising hormones. And yet, as the Cass review noted:

“Clinicians are unable to determine with any certainty which children and young people will go on to have an enduring trans identity. For the majority of young people, a medical pathway may not be the best way to manage their gender-related distress.”

Autistic and gay kids have been particularly likely to be pushed towards life-changing medical treatment and surgery. We adults have created a problem for young people where before, there was none.

When I was at school kids did not worry about being trans. Because people didn’t prompt them to think they were trans. If you didn’t conform to gender stereotypes, you were not medicalised and pathologised. We didn’t create an affirmation pathway that slapped you on the back, and pushed you along towards medical intervention. We didn’t build up, and put fertiliser on, every teenage anxiety.

There are plenty of studies that show that well-meaning mental health interventions in schools can in fact make kids mental health worse, and it may be that something similar is happening here.

But this is just one issue. A highly contentious approach to sex education is now being followed in our schools, with activist providers pushing bad ideas with bad real world consequences. This post looks at some examples, the next one will look at how we got here.

There are four related concerns about what is now being taught.

- Too much too young. Some of the problem is just about age-inappropriate and sexualising content, and normalising approach to things that should not be normalised, when kids should actually feel empowered to say no.

- Gender transition is presented as uncomplicated, and puberty blockers as risk-free and reversible. A lot of material either pre-dates the Cass Review or ignores the lessons from it, e.g. that it can be difficult for kids to get off a medical transition pathway once they are put on it.

- Promoting gender ideology and the takeup of TQIA identities. A bunch of contentious ideas from gender / TQIA+ ideology are really being promoted. These include the ideas that: Biological sex is a ‘spectrum’; that we all have an inner or metaphysical “gender identity”; and that sex is just a social construct, simply “assigned at birth”. A lot of the tone of the discussion is celebratory rather than factual and crosses the line into not just describing but promoting the idea that kids should take on various trans identities.

- A “sex positive”, relationship-negative approach. Various providers take the view that sex education should be “sex positive” and so promote sex as a hedonistic activity, and criticise the idea that sex should mainly happen in a relationship.

Let’s look at some examples of each in turn. (If at the end you want more, the NSCU produced a good summary of some of the materials in 2023.)

To put the examples in context, it’s worth saying that a number of independent sex education providers come from extreme positions which are then reflected in their lessons. For example, RSE provider Split Banana explains that, “For too long, RSHE has been fearmongering, heteronormative and irrelevant – we are changing that.”

In their influential book Great Relationships and Sex Education, Alice Hoyle and Ester McGeeney are explicit that teachers should, “engage in social activism”, and “explore key concepts such as power, privilege and heteronormativity.”

One large provider was “Educate & Celebrate” (now closed). Dr. Elly Barnes and Dr. Anna Carlile described their ethos as “To smash heteronormativity by encouraging intersectionality”.

This highly political world view is then reflected in the content of lessons.

All the way through these examples, I am not seeking to persuade you of the rights and wrongs of anything, or to lecture you about what to tell your own children if you have them, still less to judge adults’ choices.

The examples are here only to point out that things are being taught which a significant number of reasonable parents would not agree with being taught at that age.

Examples of the problems

1) Too much too young: age-inappropriate and sexualising content

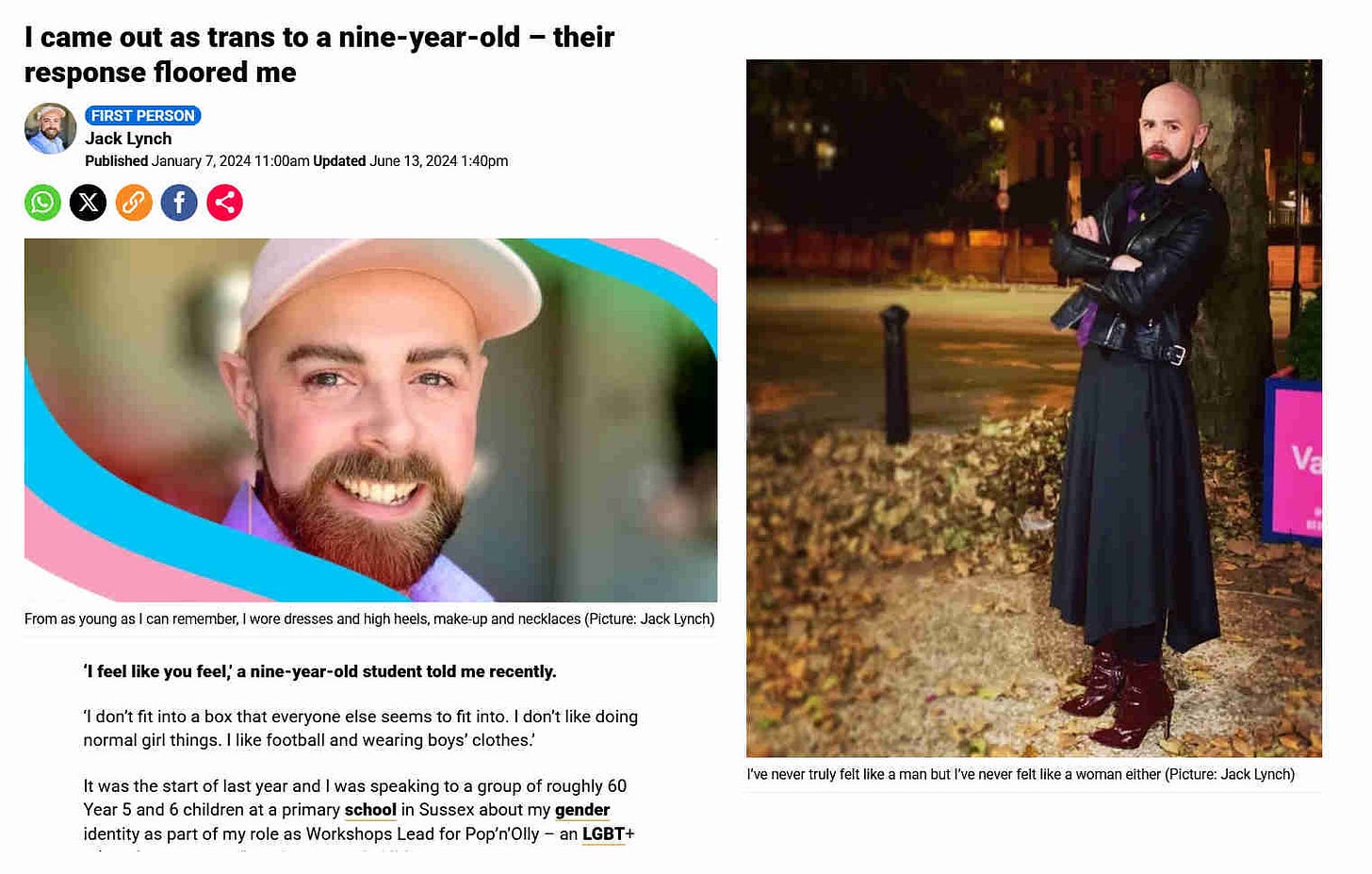

Current guidance encourages sex education in primary school. RSE provider “Pop’n’Olly” focus on primary schools. Jack Lynch estimates that he has worked with 100,000 children, and talks about how he “comes out” to nine year olds as transgender and non-binary.

However they feel more generally, many parents may feel nine years old is simply too young for such conversations about these recently-invented concepts.

Leaflets handed out at primary schools by the charity Swindon and Wiltshire Pride teach children that there are 300 different LGBT pride flags, including the “polyamory Pride flag”, flags for people who are “trigender” or “omnisexual”, and “lesser known identities across the fetish spectrum.”

The use of the ever-expanding list of colourful gender identity flags as a way into promoting gender identity politics (and some clearly adult content) to children is quite a common trope for a number of sex education providers.

The leaflet also contains a list of links, including to gender conversion group Mermaids, the “gender construction kit” and where they can get kit for breast binders.

I say all this not to criticise adults who might identify with these identities, or want to have surgery.

The point is simply that teaching primary school children about polyamory, the fetish spectrum and how to get breast binders – in taxpayer-funded schools – is inappropriate.

Various providers also talk about masturbation midway through primary school. For example, Coram Education explain they introduce this subject in year four of primary school (that’s girls and boys aged 8 and 9).

“At SCARF we believe that masturbation would come under the statutory requirements to teach Changing Adolescent Body under Health education, where children should know: key facts about puberty and the changing adolescent body, particularly from age 9 through to age 11… In SCARF we have two lessons that include masturbation. The first is in a Year 4 lesson in the Growing and Changing unit”

How many parents think that masturbation should be taught at this age? (Full disclosure, my daughter is in year four, and I don’t.)

As well as the age at which sensitive subjects are introduced, there is a problem about the normalisation of all kinds of activities and lack of any values framework. The only message is that everything is fine as long as there is some element of consent – whether it be sex with older people, or things like choking.

If in the 1990s we had asked our teachers if it is OK to choke a girl during sex they would have said – absolutely not.

But in some schools that’s not the answer today. Bridgend county borough council in Wales produced materials saying: “It is never OK to start choking someone without asking them first and giving them space to say no…. Pornography is not designed to be an educational resource, it’s entertainment. So a scene that involves choking is not going to show the consent negotiations or safety protocols that you would see if this were practised in real life.”

This is normalising a dangerous thing. It basically says it’s all fine as long as there is consent and you are careful. But many parents will think choking a girl is misogynistic, bad, unloving and… not actually what we want to normalise for kids. Many will think that if this issue is to be raised at all, girls should be empowered to tell boys who want to act out stuff they have seen in porn to get lost. It’s amazing that as Parliament is passing laws to ban strangling in online porn, some in schools are framing it as an issue mainly of consent.

And social media is a crucial part of the story here. The rise of a smartphone-based childhood is exposing kids to fairly extreme porn at a young age (a problem for another blog) and yet the response of too much sex education is just to normalise this or seek to focus on making it “safe”, without having the courage to bring out the downsides or counter-opinions.

A lesson plan used in an independent school for year eight asked twelve-year olds: “Write down the things you know about this type of sex: Anal sex. Oral sex.”

These sort of normalising discussions (all the more awkward when in a mixed-sex group) are encouraged by the textbook Great Sex Education, which says the two lesson goals in such sessions are:

1. To challenge the assumption that when someone refers to ‘having sex’ they mean penis-in-vagina sex.

2. To clarify that there is no such thing as ‘gay sex’

In a sense such lessons are just going with the flow of, rather than pushing against the impact of the rise of online porn, which increases expectations among some boys and young men that women should agree to anal sex. The impact of this shift is having real world effects, as articles in the Guardian and British Medical Journal explain:

“Women in the UK are suffering injuries and other health problems as a result of the growing popularity of anal sex among straight couples, two NHS surgeons have warned. The consequences include incontinence and sexually transmitted infections (STIs) as well as pain and bleeding because they have experienced bodily trauma while engaging in the practice, the doctors write in an article in the British Medical Journal.”

So, rather than a relentless academic focus on trying to “smash heteronormativity”, RSE could be responding differently to what’s happening, and telling kids that they can say no to the bad ideas pushed by porn and Andrew Tate-type misogynists. We could tell girls they can tell boys to sod off if they push them to do something they don’t want to – instead of making girls feel like they are prudes or outliers if they don’t want to have to negotiate with this. We could also tell boys that Tate-type ideas (that real men must humiliate and dominate women) are wrong and pathetic.

Given that the internet exists, when people are invited into schools children are likely to follow up by looking at their wider work. Highfield School in Matlock held a drag queen workshop. The workshop for 11 years olds is by Matt Charlton, aka drag queen & adult entertainer Amandah Hart. The local women’s rights network argue that drag is both sexist and always previously seen as adult entertainment. And as they have pointed out, by being in the school, kids are then likely to look up his name and find adult content e.g. his film about blow jobs.

2) Gender transition is presented as uncomplicated, and puberty blockers as risk free and reversible.

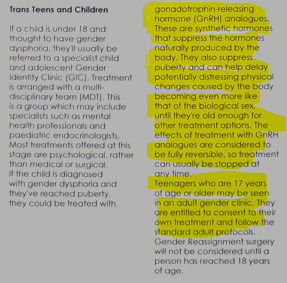

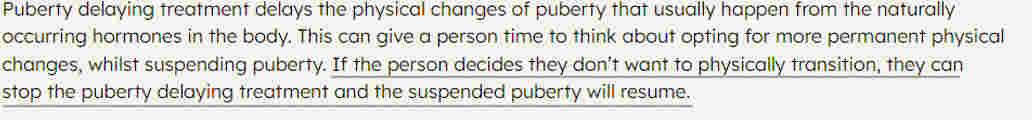

Here’s some material from a Yorkshire-based school trust.

This is telling kids that puberty blockers are totally “reversible” and risk free.

But as the Cass Review pointed out – this is just not true. Examples abound of people who regret taking them, given sometimes irreversible consequences like infertility.

Here are some teacher training materials, jointly published by Brook and Gendered Intelligence in the last quarter of 2023. These are some of the biggest providers. And yet it’s wrong. It implies there’s no risk, and that your “suspended puberty will resume”.

.

Sadly, this is wrong. Just listen to the testimony of people like Keira Bell in the UK or Chloe Cole in the US or the many others who regret taking these drugs, and the irreversible effects they have had.

So many publishers simply gloss the issues here and make transition sound like it is a perfect and simple solution. The idea of changing sex is mentioned, but the downsides, difficulties and limits of this are not mentioned.

Take Collins’ textbook “Your Choice”. It tells children: “Some people want to change their gender through surgery or hormone treatment, but not everyone does”, and then just… moves on. If these issues are to be raised, don’t they need to be addressed properly, without the problems being swept under the carpet? And given the seriousness of the medical issues involved, it is worth asking if this topic should be proactively raised in schools at all?

3) Promoting ideas from gender ideology & the takeup of TQIA+ identities

One of the ironies of contemporary sex education – and the transgender debate more generally – is that many of the ideas being promoted by the activist groups providing sex education in schools are in a way… well, extremely un-PC.

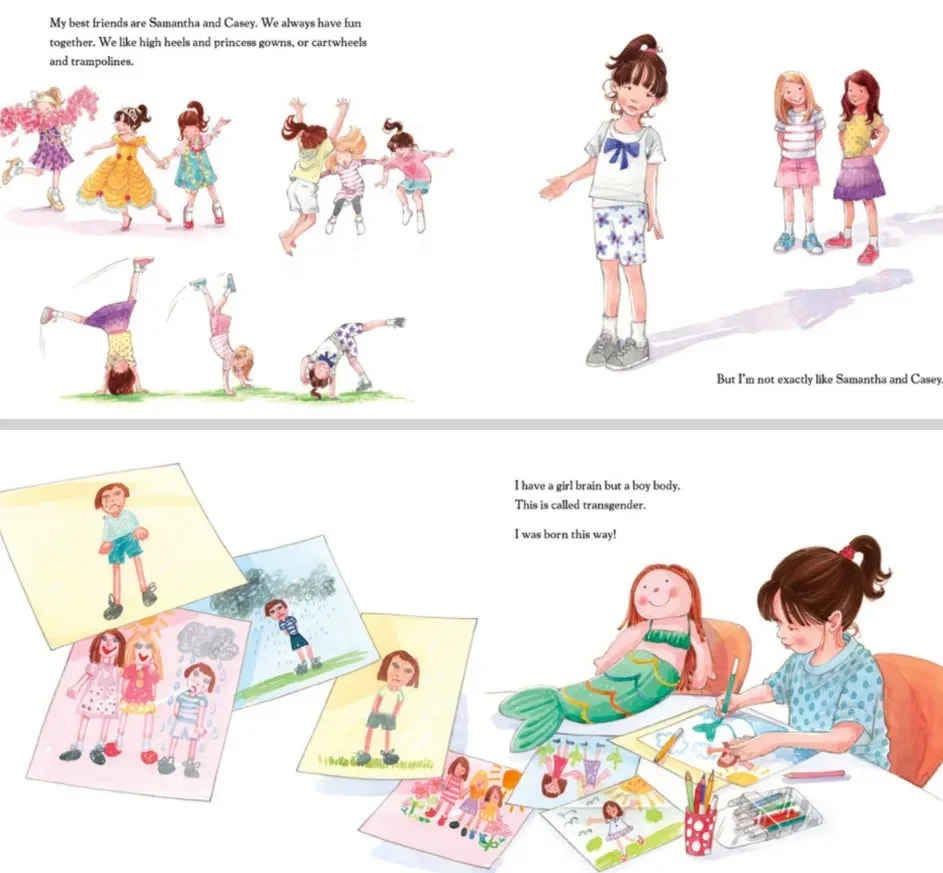

Too many schools and textbooks are now strongly pushing the ideas that there are big differences between “girl brains” and “boy brains”, and that interest in the stereotypical aspects of the opposite sex can mean that someone is “really” a member of the other sex.

While for much of the postwar period education sought to de-emphasise differences between men and women, boys and girls, the new gender ideology seeks to emphasise stereotypical behaviours. Example: here’s an excerpt from the book “I am Jazz”, which is in a lot of primary school libraries:

The retro idea used here, that there is such a thing as a “girl brain”, has no scientific meaning. Just because a boy (age 4-11) is interested in dresses, or is best friends with girls, does not mean that he is transgender – in my view this is an extremely irresponsible thing to prompt small children to think.

Some secondary schools stock Laura Kate Dale’s book, “Gender Euphoria: Stories of joy from trans, non-binary and intersex writers”

The book is essentially celebratory. As the blurb says of the pieces: “What they have in common are their feelings of elation, pride, confidence, freedom and ecstasy as a direct result of coming out as non-cisgender, and how coming to terms with their gender brought unimaginable joy into their lives.”

While positive stories about trans-identifying people have a role to play in the conversation, many schools will never tell the other side of the story: that there are dramatic medical limits to what surgery can do for you; that people change their minds and can regret transitioning; that many people who go down this route end up not with feelings of “elation” but pain, complications from surgery, regret and frustration.

The book is also normalising a bunch of things I don’t think we should normalise for 11-16 year olds.

It’s hard to be trans in the sex industry. It’s especially hard to be pre-medical transition in the sex industry. It’s even harder to be both those things and fat in the sex industry. I seem to have a huge number of labels that marginalise me. I’m a queer bisexual agender non-binary person who is disabled, schizophrenic, fat, poor and a full-service sex worker. […] I started sex work online, but soon decided to start escorting instead. I didn’t suit the webcam format, and figured I could make much more as a bona fide whore.

The most pitifully unhappy person I ever met was a prostitute I met while working with street homeless people. She was skeletally thin, had a very heavy heroin addiction, was essentially a slave to a terrifying-looking pimp, and was about to have her umpteenth baby taken off her by social services. I often think of her when people want to present prostitution as just a “career choice” like this.

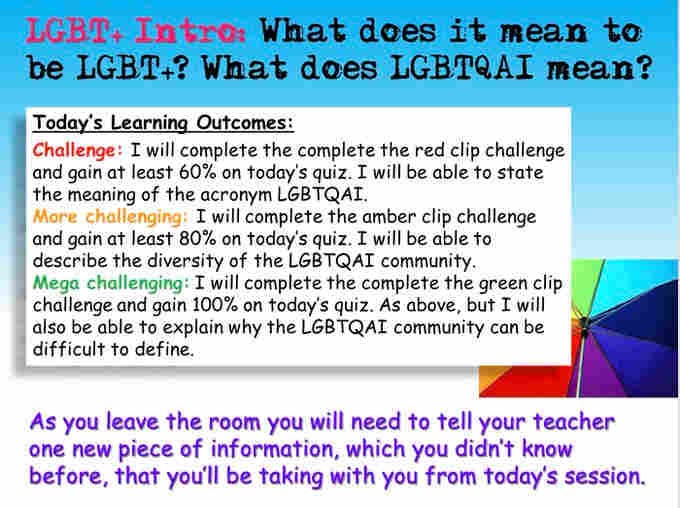

What do I mean when I say schools are crossing the line from explaining to promoting? First, we are bathing children in complex and highly questionable gender ideology from a young age, which is itself a form of promotion. Take this from Hanham Woods Academy, in Gloucestershire, flagged by James Esses.

Children are being taught that “LGBTQAI” is a factual thing like the speed of sound. In reality these are highly-contested, recently-invented ideas. What is “queer” exactly that is not gay or lesbian? What are “allies” – this is an unhelpful and catastrophist framing, when no one is at war here. Rather than being taught different views, kids must parrot the party line to score 100%.

Children are taught the difference between agender and cisgender, bigender, gender-fluid, and non-binary. These are recently made-up terms, but trusted adults are teaching children these terms and in doing so, sometimes strongly implying they should ‘identify’ with one of these.

These concepts didn’t even exist until recently, yet now kids are being indoctrinated into them, rather than just exposed to them as one person’s opinion. Many parents will feel if this ideology is to be mentioned there should be a critique.

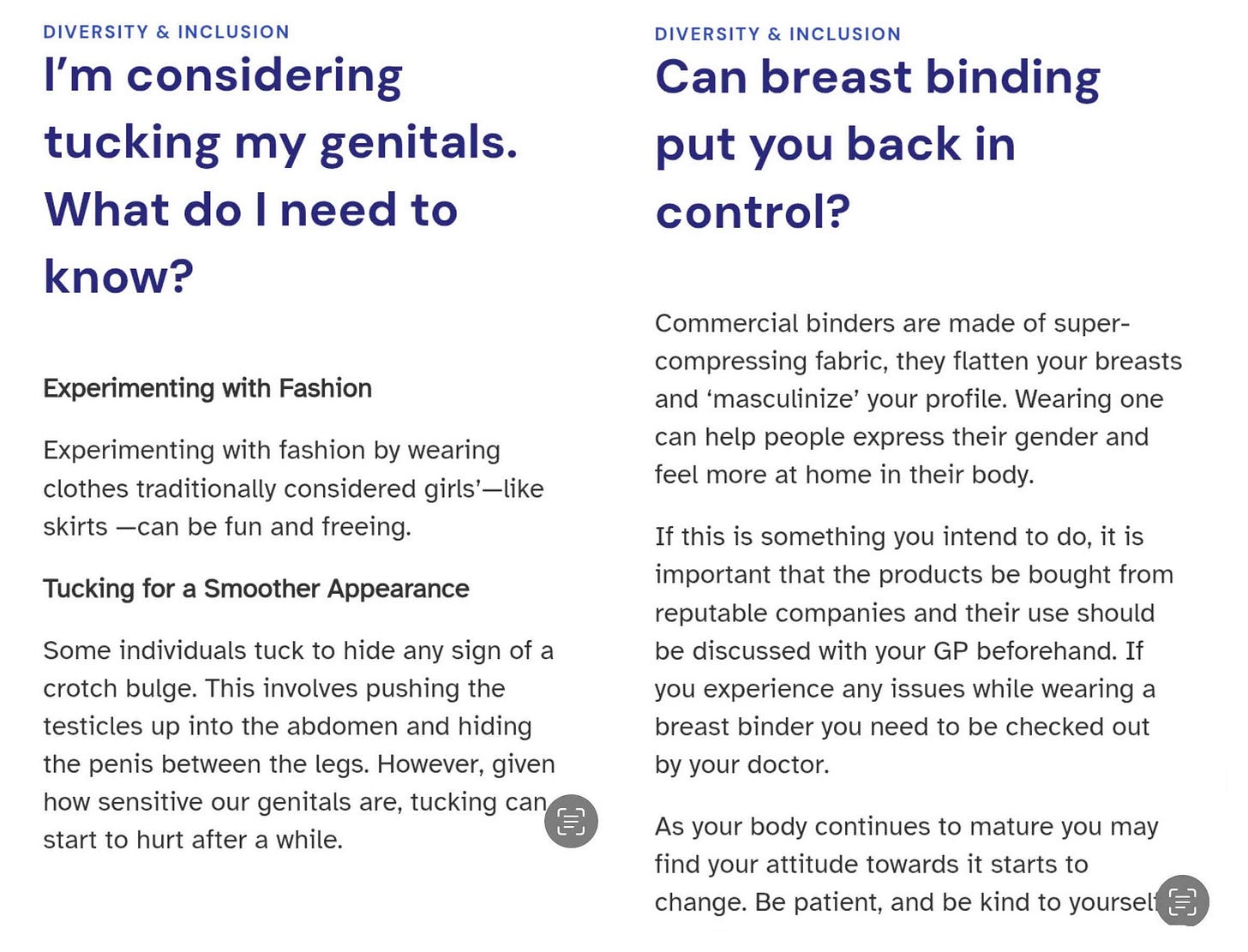

The whole way these ideas are presented is to sell them as positive, rather than give any balanced account. Another example via James Esses is from an external provider called ‘The Wellbeing Hub’. People used to criticise the victorians for bending women’s bodies out of shape with corsets and so on, but now schools are promoting equivalents in the most positive terms. Genital tucking is “fun and freeing”. Girls binding their breasts will help them “feel more at home in their body”. Could there be any long term downsides or consequences of putting kids on this pathway? They aren’t mentioned here.

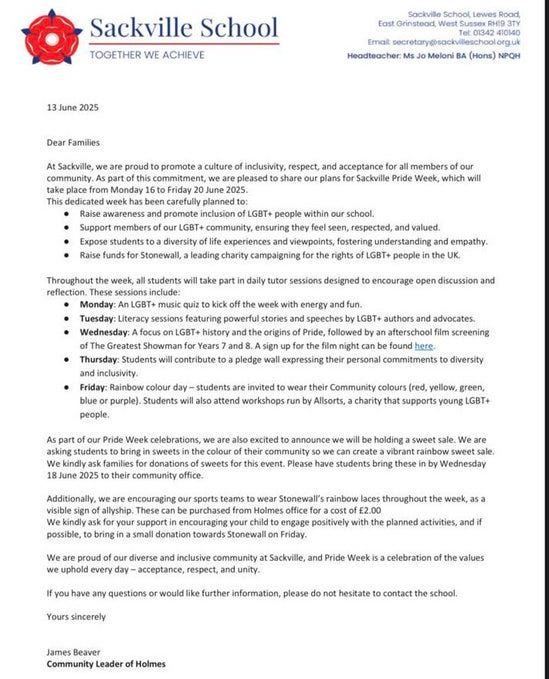

Some schools also push compelled speech and participation in various ways. This Sussex secondary school for example, says that children “will” make personal pledges on diversity and inclusion, and should bring in a donation to Stonewall. Apart from anything else, this seems like it may be breaking the law on political neutrality in schools.

.

4) A “sex positive”, relationship-negative approach

One provider of sex education in schools is the “School of Sexuality Education”, who say they “have worked with over 120,000 students since 2017”. They describe their approach as “sex positive”.

What does that phrase mean? Their response to the government’s 2019 consultation says that good sex education: means “avoiding giving problematic credence to long-term relationships and marriage”. They complain that the 2019 guidance:

appears to suggest that sex is best had within relationships, and therefore, casual sex or multiple partner sexual relationships is implicitly negative or wrong…

They say this is:

out-of-touch with the Tinder generation, therefore, also not adequately preparing some for the realities of the way in which they will choose to live their life.

They complain that in their view, even current very neutral guidance:

“both explicitly and implicitly places monogamous, long-term relationships and marriage above other forms of relationships. For example, stating a link between “committed, stable relationships” and “how these relationships might contribute to human happiness and their importance for bringing up children”

We see this presentation of a hierarchy of relationship types to be highly outdated, not to mention unrepresentative of a large proportion of modern day lives. For those who are personally in or whose family consists of ‘non-conventional’ relationships, such as co-parenting arrangements or polyamorous relationships, this would be extremely alienating and contribute to a culture of judgement and shame.

You, as an adult, can feel free to agree or disagree with all this. But I (and quite a lot of other parents) think schools should teach that sex is something for “committed stable relationships” and that a life of casual sex is unlikely to lead to long term contentment. And I don’t agree to people promoting Tinder-style hookups to children at taxpayer expense.

What does a sex positive approach look like in practice? Here’s one example from a school in London.

Students are shown photographs of the “Great Wall of Vagina”, with the caption “all genitalia are beautiful”. In a video recommended to students, entitled ‘Masturbation: It’s Good For You’, students are instructed “if you’re feeling horny, go ahead and masturbate”.

Students are told that “someone who is sex-positive would be equally accepting of a four-way polyamorous relationship, BDSM casual sex, and garden-variety heterosexual monogamy: as long as everything happens between consenting adults, all expressions of human sexuality are permissible.”

What happened to er, love and commitment? They seem to have been minimised.

Likewise, popular textbook Great Relationships and Sex Education, advises teachers to “emphasise that love and affection are often important parts of good sex, but not always. For others, good sex is quick, rough and anonymous. You can also explore the fact that some people enjoy feeling pain during sex, which is often referred to as kink or BDSM.”

RSE provider Split Banana advise teenagers 16+ that:

“It’s about time we cancelled virginity – let’s prioritise pleasure instead”

“You don’t lose your virginity, there’s nothing to lose! Only experience and information to gain.

Even very mainstream textbooks now lean so hard into non-judgementalism that they fail to do and say things that will keep children safe. Take Collins’ textbook “Your Choice”. It begins:

“If and when you decide that you are ready to have sex”

With no sense that some ages might be too young to make this “decision” It continues by normalising sex for very young children:

“If you are age 13 to 16 you have the same rights as an adult to obtain free and confidential advice from a doctor, nurse or pharmacist. They will recommend the best method for you and can supply contraceptives without telling your parents”

And

“Sex can happen between two people who don’t have a long term relationship… It can occur between two people who are friends or two people who have only just met”

The combined impression is to tell thirteen year olds that it is normal and not at all unusual for them to be having sex, that they are just like sovereign adults who should just choose whatever they like, including casual, non-relationship based sex.

This is catastrophic advice which puts young children at risk.

Conclusion

Miriam Cates points out adults’ double standards here:

Imagine you attend a training course at work. Your manager stands up and begins a PowerPoint presentation. He proceeds to show you and your colleagues a series of explicit images and graphic descriptions of sex acts that you might like to try. You are then asked to tell the group what you feel about masturbation.

Most adults would find this horrifying. If compelled to take part in this “training”, you may be able to sue your employer for sexual harassment. Yet this is a situation experienced by children in British schools in Relationships and Sex Education (RSE) lessons.

We’ve drifted into a position where instead of neutral information, too much sex education promotes, pushes and celebrates a set of ideas with bad real-world consequences. Many parents would not agree with what is being taught to their children – if they were even allowed to see it.

Parents should not be put into a position of feeling like they have to withdraw children from sex education lessons by extreme or ideological teaching.

In England we don’t count how many children are withdrawn from sex education, though a one-off study found a third of schools had at least one child withdrawn. But in Scotland they do count, and we can see how an increasingly radical approach (and the Scottish government’s own Gender Bill) has been driving parents away: the number of children being taken out of sex education classes quadrupled between 2019/20 and 2023/24.

To conclude, while there is some perfectly good sex and relationships education happening in many schools, there is too much that is not. The next part of this post will look at how we got here, and what to do about it.

This article (Sex education in schools: part one) was created and published by Neil O’Brien and is republished here under “Fair Use”

See Part Two Below

Sex education in schools: part two

Schools are trying to navigate a minefield, but the government it sitting on its hands – with bad consequences for kids

NEIL O’BRIEN

The first part of this post looked at how sex education in our schools has gone wrong. This second part looks at why and how this happened.

Let’s start with recent developments, then we’ll rewind a bit further.

In December 2023, the Department for Education published a consultation on draft non-statutory guidance for schools and colleges in England on children questioning their gender. The consultation was open until 12 March 2024.

Then Minister for Women and Equalities, Kemi Badenoch said:

This guidance is intended to give teachers and school leaders greater confidence when dealing with an issue that has been hijacked by activists misrepresenting the law.

Yet here we are in summer 2025, and it still hasn’t been issued. New Secretary of State Bridget Phillipson is still “thinking about” the guidance.

Likewise, in the summer of 2023 Rishi Sunak answered a call from Miriam Cates for an urgent review following reports of inappropriate sex education lessons, resulting in the government publishing a draft statutory guidance in May 2024 and opening a consultation on RHSE – Relationships and Sex Education (RSE) and Health Education.

That closed in July last year, but nearly a year later, nothing has been published. Again, the new government is “thinking”.

But while the government ponders endlessly, schools are trying to navigate their way through a minefield of difficult issues every single day.

What was the last government trying, belatedly, to fix? And why is the new government finding it so hard to make up its mind?

The basic problems are these:

- There is little or no consensus on what should be taught at what age, and in many cases what is taught is a long way out of line with what many parents would want.

- Provision of lesson plans and materials has increasingly come from unregulated third parties, often radical campaign groups, leading to safeguarding failures.

- These groups abuse copyright law and their subscription models to block parents and others from circulating or discussing their materials. This prevents parents from discussing legitimate complaints, and blocks both democratic discussion and proper regulatory oversight.

How did we get here?

How we got here: 1945-2019

For most of the postwar period education about sex and relationships was regarded as first and foremost a matter for parents. For most of the postwar period Britain was a relatively homogenous country with a greater level of consensus about moral and social issues than it has now.

For example, as part of the state takeover of schools after the war, it was agreed that all pupils in state schools in England and Wales must take part in a daily act of Collective Worship, “of a broadly Christian character” unless they have been explicitly withdrawn by their parents – indeed, this is notionally still a requirement.

Though the Board of Education conducted a survey of what schools were teaching about sex in 1943, schools were generally left to their own devices. The Department of Health were keener than the Department for Education on the idea of sex education, which they hoped would reduce sexually transmitted diseases. But both the teaching unions and the DFE were wary of centrally dictated sex education, so the department confined itself to issuing various forms of fairly uncontroversial guidance, like “School and the Future Parent.”

Sex education rolled out in schools in stages. The 1986 Education Act specified that where there was sex education it should promote moral values and family life, and that each school and LA should have a published policy on whether they offered sex education, and the contents of it.

It was the 1993 Act that first made sex education compulsory – in two ways. First, the basic biology of reproduction became part of the national curriculum for science. Second, all secondary schools were required to offer sex education. It says something about the health-driven motives for this move that the one specific requirement to be mandated was that sex education should include information on AIDS and STIs. Though provision of sex education was made compulsory attendance was not: the trade off was that parents were given the right to withdraw their children from these lessons. This was regarded as an important way to maintain the principle that parents not the state should be able to decide how their own children are taught about these issues.

Sex education was highly focussed on factual, biological information relating to procreation, contraception and the avoidance of sexually transmitted infections. In so far as there was an ethical framework coming with it, it was a consensus-maximising, small-c conservative agenda. Accompanying the new law, the 1994 guidance stated:

The purpose of sex education should be to provide knowledge about loving relationships, the nature of sexuality and the processes of human reproduction… It must not be value-free; it should also be tailored not only to the age but also to the understanding of pupils.

Pupils should accordingly be encouraged to appreciate the value of stable family life, marriage and the responsibilities of parenthood. They should be helped to consider the importance of self-restraint, dignity, respect for themselves and others, acceptance of responsibility, sensitivity towards the needs and views of others, loyalty and fidelity. And they should be enabled to recognise the physical, emotional and moral implications, and risks, of certain types of behaviour, and to accept that both sexes must behave responsibly in sexual matters.”

Updated guidance in 2000 showed some significant shifts but also a lot of continuity in the Blair era – the carefully-negotiated paragraphs below give a flavour:

As part of sex and relationship education, pupils should be taught about the nature and importance of marriage for family life and bringing up children. But the Government recognises – as in the Home Office, Ministerial Group on the Family consultation document “Supporting Families”- that there are strong and mutually supportive relationships outside marriage. Therefore pupils should learn the significance of marriage and stable relationships as key building blocks of community and society. Care needs to be taken to ensure that there is no stigmatisation of children based on their home circumstances. […]

What is sex and relationship education? It is lifelong learning about physical, moral and emotional development. It is about the understanding of the importance of marriage for family life, stable and loving relationships, respect, love and care. It is also about the teaching of sex, sexuality, and sexual health. It is not about the promotion of sexual orientation or sexual activity – this would be inappropriate teaching.

So on the one hand no stigmatisation, but on the other, an ongoing emphasis on “stable and loving relationships.” The Learning And Skills Act 2000 reaffirmed similar points in law:

The Secretary of State must issue guidance designed to secure that when sex education is given to registered pupils at maintained schools—

(a) they learn the nature of marriage and its importance for family life and the bringing up of children, and

(b) they are protected from teaching and materials which are inappropriate having regard to the age and the religious and cultural background of the pupils concerned.

In the years that followed there was a lot of lobbying from activist groups for compulsory sex education and more ‘progressive’ content. A big milestone moment of change came in 2014 with the publication of “SRE for the 21st Century – Supplementary Advice”

First, the content of it was a major shift from the guidance of 2000, with multiple references to the contentious concept of “gender identity”, encouragement to teach about pornography, sexting, and a heavy emphasis on children’s rights and inclusion. It also heavily emphasised for the first time the inclusion of transgender issues:

Teachers should never assume that all intimate relationships are between opposite sexes. All sexual health information should be inclusive and should include LGBT people in case studies, scenarios and role-plays. {…}

Schools have a clear duty under the Equality Act 2010 to ensure that teaching is accessible to all children and young people, including those who are lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender (LGBT).

But as important as the context was the process. This new non statutory guidance was issued, not by DFE, but by a consortium of third party groups with the support of the DFE: “The Supplementary Advice is supported by the DFE and a range of other government, education and voluntary sector stakeholders.”

Despite not being a government document, there were supportive quotes from coalition ministers at the start of the guidance. The guidance also encouraged the use of materials and people from third party groups.

This shift to a kind of arms-length / third-party model of “soft governance” is hardly unique – there are many such examples, from the row over the Sentencing Council’s two tier sentencing plans to Natural England’s contentious interpretation of ‘nutrient neutrality’.

But in sex education – where there is so little consensus – this shift has been particularly consequential, and opened the door to very radical trans activists. None of this should be read as a criticism of policy makers at the time: it was extremely well intentioned, but happened to be followed immediately by the period in which trans activism suddenly became much more radical and the issues much more contested.

The Relationships Education, Relationships and Sex Education and Health Education Regulations 2019, (under the Children and Social Work Act 2017) made Relationships Education (not sex) compulsory for all pupils in primary schools.

The 2019 Statutory Guidance that went with this change represented another step change. It incorporated and deepened the references to the more contentious ideas in the 2014 “Supplementary advice”, with multiple references to gender identity.

It states that, “we expect all pupils to have been taught LGBT content at a timely point”, but doesn’t explain further. While it was relationships rather than sex education that was made compulsory in regulation the guidance states that, “The Department continues to recommend therefore that all primary schools should have a sex education programme tailored to the age and the physical and emotional maturity of the pupils.” [my italics]

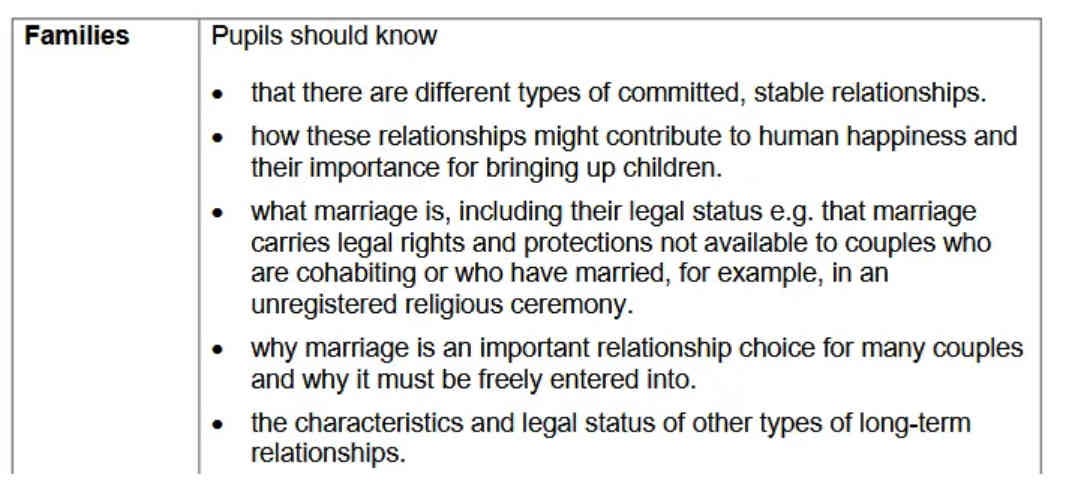

While the Blair era 2000 guidance had stressed the importance of marriage – “pupils should learn the significance of marriage and stable relationships as key building blocks of community and society” – the 2019 guidance takes a completely neutral approach:

.

Schools have been told there are many highly contentious subjects they should cover. But in contrast to many other subjects, the specification of what is to be taught is very vague. Contrast the statement that schools should “teach their pupils about LGBT” with the following physics specification for example. In physics, regarding diffraction, you will need to know the:

“Appearance of the diffraction pattern from a single slit using monochromatic and white light. Qualitative treatment of the variation of the width of the central diffraction maximum with wavelength and slit width.

-The graph of intensity against angular separation is not required.

Plane transmission diffraction grating at normal incidence.

Derivation of dsinθ = nλ

-Use of the spectrometer will not be tested.”

In contrast, in RHSE / RSE there is a lack of a clear specification of what is to be taught from the centre. Unluckily, the one thing that is quite specific – the reference to “gender identity” – has become a way in for activists to teach all kinds of extreme things.

So to summarise:

- The 2014/2019 guidance encouraged schools to teach about contentious things, but with little specificity about what should be taught – except that the controversial idea of “gender identity” must be included.

- This and the arms length creation of the 2014 guidance sent schools running to third party providers.

- Unluckily, it turned out that this was done just the moment when we transitioned from a relatively calm period of sex and gender discussion to a period of trans activism (the so called ‘great awokening’)

- We moved quite rapidly from guidance saying sex education must not be value free to guidance that was quite value free on paper….

- …And the practical effect of this has been to allow radical groups to impose their own fairly extreme values

- The steadily-percolating effects of the 2010 Equality Act (supported by same groups and forces) also created something of a feedback loop, as it was used by activist groups to browbeat schools into feeling they had to go along with their agenda.

These problems, which I will discuss below, are why in 2023/2024 the Conservative government produced the guidance on gender questioning children and the new draft RSHE guidance which, as I mentioned at the start, went out to public consultation.

The proposed new guidance was clear that: “Schools should not teach about the broader concept of gender identity. Gender identity is a highly contested and complex subject… If asked about the topic of gender identity, schools should teach the facts about biological sex and not use any materials that present contested views as fact, including the view that gender is a spectrum.”

This would have been a good start towards unwinding the issues that have emerged. But, as noted above, the current government is sitting on this guidance, and so the wild west continues. Let’s turn to that now.

From secret garden to wild west

“In any society where government does not express or represent the moral community of the citizens, but is instead a set of institutional arrangements for imposing a bureaucratized unity on a society which lacks genuine moral consensus, the nature of political obligation becomes systematically unclear.”

― Alasdair MacIntyre, After Virtue

Recent years have seen a dramatic shift towards the provision of contentious material in schools. The providers range from external campaign groups, through small, activist, one-man-band types of operations, right through to large ‘edutech’ companies.

The changes in sex education have been dramatic – though parents can’t easily see what’s going on because at present, sex education in schools is a secret garden.

Astonishingly, parents have no stated right in law to see what their kids are being taught. The private providers and activist groups who now provide much sex education and lesson materials hide behind copyright and commercial secrecy claims to prevent parental access.

Many also use online subscription charging models which are used to prevent parents and others from seeing, circulating and discussing their materials.

London mum Clare Page was denied the right to see the materials at her school, and has waged a long battle to fix this since. And yet, when we recently attempted to amend the Schools Bill to give parents a right to see what their kids are being taught and end secret lessons, Labour voted it down. One Labour MP argued that parents might be angry if they saw it. That is rather the point.

What is to be done?

The underlying problem is this.

On the one hand, there is now a dramatic lack of consensus about what should be taught or not taught. Indeed, in an increasingly hyperdiverse society, the zone of consensus is if anything shrinking: it surprises some people to learn that Londoners have the least liberal attitudes to sexuality (because of the capital’s ethnic mix). On the other hand, you there is a progressive monoculture among providers. Some are more extreme than others, but there is a monopoly of basic view.

One response to this is to argue that parents with concerns are simply wrong and should be overruled. I don’t agree with this fundamentally illiberal view – I think reasonable people can have justified concerns about what is being taught in many schools. Why?

- Gender ideology has real world consequences and leads children down a bad route. At present schools are promoting it, praising it, giving it attention and status. As the Cass Review pointed out) it can be hard to get off an affirmation pathway. Gender dysphoria was not a thing in schools in the 1990s. It is a problem that has been (and is being) created for kids by a mix of irresponsible and well meaning adults.

- The ideology being pushed relies entirely on gender stereotypes to an almost metaphysical extent – the way ideas like “girl brains” and “boy brains” are deployed are anti-scientific garbage.

- It medicalises the normal struggles and confusions of childhood, and normalises ideas that are unhelpful (“trapped in the wrong body” / you were mistakenly ‘assigned’ at birth / you like cars so you are ‘really’ a boy).

- ‘Sex positive’ sex education is a politically partisan view that does not cater for the differing values amongst parents

I think we need to end the wild west, and end secret lessons. The guidance and approach needs a big reboot. What does that mean in detail?

As a first step, the two pieces of guidance the government is sat on need to come out without the key changes being watered down. We then need much clearer regulation of what is taught, and to rethink the idea of sex education in primary schools fundamentally.

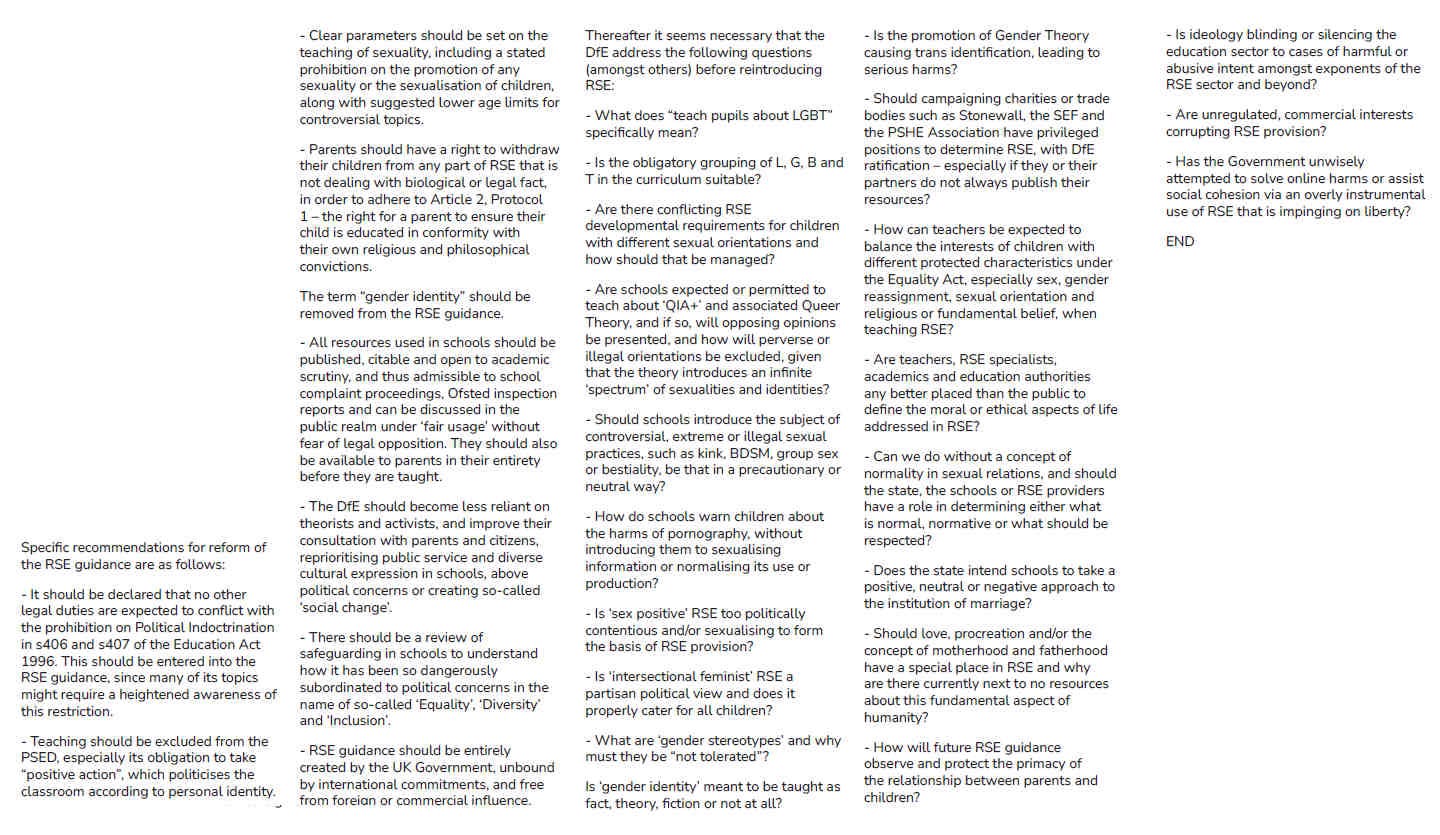

You could write a whole report on how to reboot things, but I think the list of questions and ideas produced in a report by the NSCU is an interesting place to start.

Most RHSE lessons are not taught by specialists but by form teachers – and there is no particular reason that maths teachers should be experts in the teaching of moral judgement or sexual ethics. There are good reasons these questions were mainly left to parents for a long time.

Sadly, on this one parental choice of schools isn’t much of an answer to this divergence of viewpoints: insofar as parents are able to exercise choice about which school their child goes to, the content of the RHSE curriculum is unlikely to be a big factor for most (if they can even find out what is being taught).

While we can never get to a 100% consensus, I think we need to get to something that a greater proportion of parents can be happy with – but that will mean reining in the wild west of activist sex education providers who are pushing inappropriate content to suit their own interests.

This article (Sex education in schools: part two) was created and published by Neil O’Brien and is republished here under “Fair Use”

••••

The Liberty Beacon Project is now expanding at a near exponential rate, and for this we are grateful and excited! But we must also be practical. For 7 years we have not asked for any donations, and have built this project with our own funds as we grew. We are now experiencing ever increasing growing pains due to the large number of websites and projects we represent. So we have just installed donation buttons on our websites and ask that you consider this when you visit them. Nothing is too small. We thank you for all your support and your considerations … (TLB)

••••

Comment Policy: As a privately owned web site, we reserve the right to remove comments that contain spam, advertising, vulgarity, threats of violence, racism, or personal/abusive attacks on other users. This also applies to trolling, the use of more than one alias, or just intentional mischief. Enforcement of this policy is at the discretion of this websites administrators. Repeat offenders may be blocked or permanently banned without prior warning.

••••

Disclaimer: TLB websites contain copyrighted material the use of which has not always been specifically authorized by the copyright owner. We are making such material available to our readers under the provisions of “fair use” in an effort to advance a better understanding of political, health, economic and social issues. The material on this site is distributed without profit to those who have expressed a prior interest in receiving it for research and educational purposes. If you wish to use copyrighted material for purposes other than “fair use” you must request permission from the copyright owner.

••••

Disclaimer: The information and opinions shared are for informational purposes only including, but not limited to, text, graphics, images and other material are not intended as medical advice or instruction. Nothing mentioned is intended to be a substitute for professional medical advice, diagnosis or treatment.

Disclaimer: The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of The Liberty Beacon Project.

Leave a Reply