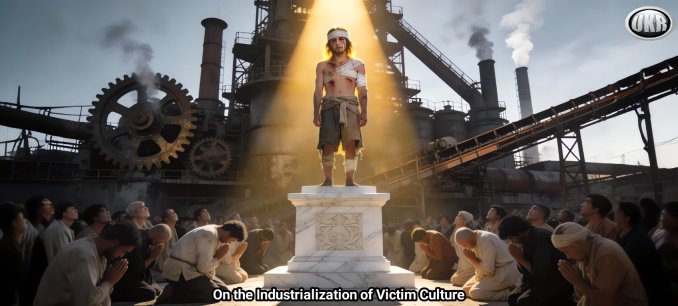

On the industrialization of victim culture

How the status of the victim became sacralized, Part One

FRANK FUREDI

It seems that these days there is a relentless demand for gaining the status of a victim. No group wants to be left out, which is why a group of cultural entrepreneurs from Manchester, England have decided that since working people get a raw deal in the arts world class should become a ‘protected characteristic’[i]. In other words, they believe that the working class should be regarded as a victim of social discrimination and join the ranks of other formally protected victim groups like women and racial and sexual minorities.

The aim of this essay is to explain the changing meaning of the term victim and its evolution into what has become one of the most valued and celebrated identity in the western world. In this Part One of our discussion of the rise of the cult of the victim our aim is to provide context for the development of the unique status of the victim. In our era of historical amnesia, it is easy to overlook the fact that the moral authority enjoyed by the victim, its subsequent politicization and its transformation into a stand-alone identity is a relatively recent development.

Remember!!! Until relatively recently being victimised did not constitute a claim to a distinct identity.

The evolution of the cult of victimhood

It is important to note that originally the word victim had very restrictive meaning. In the 15th century it referred to a ‘living creature offered as a sacrifice to God or other power[ii]. Its meaning gradually altered to refer to the experience of being harmed either intentionally or unintentionally. Its shifting focus did not simply refer to an act of harm or crime affected by an agent of force but also to the existential difficulties caused by being a ‘victim of circumstances’. Since the 1970s and 1980s, the victim category was no longer restricted to those who suffered from crime or some other act of injustice. Virtually any misfortune could be assimilated into the perspective of victimization. According to this convention, people who suffer from a physical or psychological problem are represented as victims of their condition. People do not so much have heart attacks, they are often portrayed as victims of heart attack. Alcoholics have been reinvented as victims of alcohol addiction. A multitude of new interest groups now claim that they are victims of addictive behaviour. Compulsive eaters, sex addicts, internet addicts, shopping addicts, lottery addicts, junk food addicts are some of the new group of victim addicts that were invented during the last two decades of the twentieth century.

The status of victimhood is not confined to those individuals who have directly suffered from a particular grievance. Moral entrepreneurs argued for the recognition of what they characterise as secondary or indirect victims. As one criminologist noted, ‘crime victim activists have worked to expand the concept of victim to include the family and friends of the actual victim’.[iii] Members of a family of the direct victim are often referred to as indirect victims. Victim advocates argue that family members and sometimes friends must be given access to therapeutic services and other resources. People who witness a crime or who are simply aware that something untoward has happened to someone they know are all potential indirect victims. The concept of the indirect victim allowed for a tremendous inflation of the numbers who are entitled to claim victim support. Anyone who has witnessed something unpleasant or who has heard of such an experience could become a suitable candidate for the status of indirect victim. This was the outlook that influenced the British Government’s law reform body, the Law Commission, when it recommended in March 1998 that people who suffer mental illness after witnessing or hearing of a relative’s death, even on television or radio should have the right to compensation.[iv]

The politicisation of the culture of victimhood

In the late 1970s American society and eventually the rest of the West came under the spell of a culture of victimhood. This was the moment that saw the sacralisation of the victim. It was now argued that victims can never be blamed for their predicament and that they must always be believed and certainly never subject to any serious questioning. At this point in time victimhood became politicised and elevated into an issue that constantly haunts the media landscape. There are many important reasons for the remarkable public consensus driving the politicisation of victimhood. But the precondition for its remarkable success is its transformation into a secular sacred identity which coincided with a growing sense of powerless, which from the late 1970s onwards was most strikingly illustrated by the diminished belief in human agency

The sacred status off the victim is taken for granted to the point that its unique status is often overlooked. Yet the victim plays a curious role in contemporary Western society. Almost everyone swears by it and almost nobody is prepared to question the claims made on its behalf. The victim movement is in effect the beneficiary of unquestioned moral authority. At a time when virtually every institution – including the church – is subject to an unprecedented level of scepticism, the special position of the victim’s movement provides a striking contrast to the norm. Victimhood and suffering provide a warrant for public recognition and for special treatment. The very mention of the word victim inspires a feeling of reverence and gains automatic respect. That is why public figures of all shades of political opinion are so determined to be associated with this cause. They regard their association with the cause of the victim as evidence of character and moral integrity.

Unlike most social movements, that of the victim has achieved most of its original goals. Victims’ rights and victim compensation programmes have been adopted in Britain and in all the states of the US. Most European Union countries have also gone down the road of providing resources for their victims. Important legal changes designed to privilege the position of the victim have been implemented swiftly and with little opposition. The usual heated exchanges that surround changes in the system of justice have been conspicuously absent in this instance.

More specific laws that deal with high profile victim issues such as child abuse, rape and stalking have tended to be passed in record time and without much fuss. In 1984 in California, where many of these laws were innovated, 29 bills dealing with child abuse were introduced in the Legislature. The Child Abuse Prevention Training Act went through on the nod, even though politicians were very much concerned with the rising cost of social spending. This point was stressed by Berrick and Gilbert, who noted that although California had a republican governor who looked upon costly programs with some reservation, the Prevention Act sailed through the state senate with virtually no opposition and drew only two opposing votes in the assembly’. The social scientist, Philip Jenkins drew attention to a similar pattern at play in Britain. Jenkins’ excellent study of moral panics in Britain during the eighties, raised interesting questions about the ‘rapid acceptance of child abuse as a primary social problem’. He believes that the ‘triumph of the abuse issue’ owed much to ‘the lack of serious opposition’. According to him, the view that incest was widespread, ‘could be employed in various ways by activists of all political shades, moralists and feminists, conservatives and socialists’.[v]

Although, the advocates of the victims’ movement claim that it is a ‘separate political force’, it seems to exist above the usual debates and conflict that surrounds political life.[vi] On the contrary, the victim receives the support of all shades of political opinion. Traditional opponents like right-wing republicans and liberal democrats are all on the side of the angels as far as the issue of the victim is concerned. For example, in 1998 Jon Kyl, a Republican senator from Arizona and Dianne Feinstein, a Democratic senator from California collaborated on a highly publicised initiative to amend the American Constitution by introducing the concept of victims’ rights. Such initiatives continue to enjoy strong bipartisan support. A succession of proposals in Britain, designed to make the legal system more victim friendly were backed by all parties in Parliament. Strongly opinionated movements, who are usually at each other’s throats, e.g. Christian fundamentalists and cultural feminists, all enthusiastically embrace the cause of the victim. This is a safe and caring issue, which attracts the interest of every ambitious politician. As one study of this movement concluded, ‘victim rights is an issue that enjoys wide-ranging support because no one wants to be seen as being “against victims”.’[vii] The American sociologist, Joel Best believes that victim rights has ‘bipartisan appeal’. ‘Republicans like the opportunity to “get tough on crime”, while Democrats can emphasise their commitment to protecting women, children, ethnic minorities, and others vulnerable to victimization’ wrote Best.[viii]

It seems that everyone regards the victim with reverence and any initiative that claims the banner of victims’ rights is likely to enjoy at least rhetorical support. The special status of the victim is so deeply entrenched that even critical thinkers rarely ask the question of why this has come about. Ezzat Fattah, a veteran victimologist based in Canada was one of the rare examples of a scholar prepared to raise doubts about the lack of critical thinking on this subject. He noted that ‘surprisingly, there has been very little scrutiny of the actions of the victims’ movement and very few critical assessments of its achievements’. And he added, that ‘victims’ rights legislation and programs to help victims of crime have been greeted with enthusiasm and have encountered very little or no opposition’.[ix] Fattah was clearly suspicious of the ‘exceptional speed’ with which victims were discovered and has called for the questioning about the ‘real interest and motives’ behind this process.[x] Our series of essays in the weeks to come aims to explore this important but often unquestioned development.

Politics of Powerlessness

The emergence of the victim consensus is often celebrated as a reflection of a new positive caring sensibility. Victim advocates continually declare that we have become more aware and more sensitive to the plight of others. Public displays of grief for tragedies are becoming increasingly frequent and experts in the media never tire of pointing to the new compassion of a society that is more and more concerned with pain and suffering. One central paradox often escapes this tone of self-congratulation towards the cult of vulnerability. The victim consensus is probably the most enduring legacy of the so-called ‘greedy eighties’. The political era associated with Reagan and Thatcher are conventionally presented as one of unbridled selfishness, symbolised by the uncaring yuppie and the callous pursuit of self-interest. Yet it is precisely at this time when society was meant to be so indifferent to the plight of the weak, that the culture of victimhood became institutionalised. Paradoxically it was the conservative regimes of the eighties that gave prominence to the victim and it was during their regime that the consensus around it was formed. The institutionalisation of the cult of vulnerability during a time, which was by all accounts not defined by compassion suggests that its existence may have little to do with the rise of enlightened opinion. Indeed, it has far more to do with the fragmentation of everyday life, that became increasingly pronounced in the eighties than a sudden outburst of compassion.

Many commentators claim that the greedy eighties had encouraged the development of a strident individual consciousness. However, this analysis confusingly ascribes to the individuation of society the growth of a powerful individual consciousness. During the eighties, western societies were subject to strong influences which had the effect of fragmenting social experience. This had a major impact on people’s lives and helped to normalise a more privatised and individuated form of lifestyle. But the weakening of traditional communities and other civic institutions did not have the effect of stimulating the growth of rugged entrepreneurial culture of individualism. On the contrary, the erosion of old social links helped to intensify a sense of isolation and weakness. One outcome of this process has been, what elsewhere I characterise as a Culture of Fear – intense social anxieties underwritten by a heightened sense of being on your own without any obvious means of affirmation and support[xi]. This consciousness has had the effect of altering the way that people see and manage their relationship with the world. One of its characteristic features has been the consolidation of an exaggerated sense of powerlessness. It is at this point in time that the term ‘vulnerability’ became embraced as the distinct identity and communicated through the newly invented term, ‘the vulnerable’.

Most readers under the age of fifty are likely be unaware of the fact that the term vulnerable in association with people only came into usage in the 1980s and 1990s. My analysis of UK and US based newspapers through the database LexisNexis and the index of The Times and New York Times indicates that in 1960s and 1970s the term vulnerable was very selectively applied to children and elderly. In the 1980s, ethnic minorities, the homeless, single parents, the mentally ill, people in care and the unemployed were added to this list.

A search of UK newspapers indicates that since the 1990s, vulnerability has encompassed the experience of a new range of emotional distress of ‘depressed men’, ‘stressed employees’ and career women.[xii]In more recent times, young Muslim men, university students, teenagers under pressure to be thin, people addicted to Internet pornography are only a small sample of the numerous constituencies who have been characterised as vulnerable[xiii]. In the vernacular, on the media, in official policy statements and even in academic discourse, vulnerable has frequently replaced the terms poor and disadvantaged. ‘One law for the rich, one for the vulnerable’ ran the headline of one broadsheet’.[xiv] A similar pattern is evident in the US. By the 1990s the term vulnerable was commonly used to refer to virtually every group facing a difficult predicament. One New York Times headline ‘We’re All Vulnerable Now’ illustrates this sensibility.[xv] In recent decades the term vulnerable is so causally applied to groups and individuals that literally every unpleasant experience can interpreted as its source.

The proliferation of groups designated as vulnerable ran in parallel with the widespread acceptance of a fatalistic view of the human experience. Since this point in time surveys constantly claim that people expect that the future will be worse than today. This fatalistic tendency continually emphasises the negative side of every development. Even periods of relative economic prosperity fail to stimulate what commentators call the ‘feelgood factor’. The difficulty which society has in feeling good about itself is but an expression of a mood in which the anticipation of the worst possible outcome has become routine. A Culture of Fear emerged which has encouraged a tendency to regard every new innovation as a potential vehicle for a disaster.[xvi]

Since the Reagan-Thatcher years, politicians, sensitive to a prevailing mood of malaise continually promise to ‘empower’ this or that constituency. However, the very rhetoric of empowerment gives the game away for it is based on the premise of a subservient public who are passively dependent on the good offices of the politician. That is why every undertaking that promises more empowerment serves only to remind people of their subservient and powerless status.

The sense of powerlessness is further enhanced by a political elite that has clearly lost its nerve. Politicians and the media continually point to the mounting dangers facing society. Social critics and political activists revel in stories about X-files cover-ups over poisoned food, lethal pollutants, new diseases and other threats to human survival. It seems that, regardless of their point of departure, commentators of different shades of opinion are now likely to arrive at a strikingly similar conclusion: that the world is an increasingly dangerous, out-of-control place.

Just last week we humanity was warned about an impending Apocalypse. This warning emanated from a group of scientist who belong to a group who at the dawn of the nuclear age created a Doomsday Clock as a symbolic representation of how close humanity is to destroying the world. Last Tuesday, nearly eight decades later, the clock was set at 85 seconds to midnight — the closest the timepiece has ever been to midnight, according to the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, which established the clock in 1947[xvii]. Midnight represents the moment at which people will have made Earth uninhabitable[xviii].

Such doom-mongering highlights the conviction that as against the run-away threats facing the planet humanity is powerless. And it is the sense of powerlessness which helps to create a terrain on which the cult of vulnerability can thrive. The sense of vulnerability goes hand in hand with the expectation of victimisation and suffering. This is a form of consciousness that readily identifies with the victim.

Elsewhere I have characterised this form of consciousness as an expression of the steady diminishing of human subjectivity during the past fifty years[xix]. The celebration of the victim and a pervasive sense of victimisation is underpinned by the development of an intensely fatalistic account of human potential. The narrative of people as the victim of circumstances assumes that they are powerless to influence their destiny. Consequently, victim culture encourages an orientation of deference to Fate. Indeed, one of the most unattractive features of the cult of the victim is its promotion of passivity in face of the challenges we face..

Characteristically the diminishing of subjectivity leads to the objectification of human experience. In accordance with this development people are less and less regarded as the subjects of history and more and more assumed to be its objects. This suppression of the human agency and its gradual displacement by a consciousness of victimhood has important implications for the way we regard people. The downsizing of the role of the subject entails a rejection of the classical humanist ideal of personhood.

The prevailing sense of diminished subjectivity is underwritten by a distinct code about human behaviour. Every culture provides a set of ideas and beliefs about the nature of human beings and what constitutes their personhood. Our ideas about what we can expect from one another – how we handle uncertainty and change, deal with adversity and pain, how we view history – are underpinned by the current cultural view of the human potential. And the defining feature of the Western twenty-first century version of personhood is its vulnerability. Although society still upholds the ideals of self-determination and autonomy, they are increasingly overridden by a more dominant message that stresses human frailty.

This model of human vulnerability and powerlessness is transmitted through ideas that call into question our capacity to control our own lives and affairs. Social commentators regularly declare that we live in an era of the ‘death of the subject’, ‘the death of the author’, ‘the decentred subject’, ‘the end of history’ or ‘the end of politics’. Such pessimistic accounts of the human potential inform both intellectual and cultural life in the West, providing a cultural legitimation for the downsizing of human ambition.

How people cope with painful encounters and unpleasant existential problems is strongly influenced by cultural and historical factors that shape the way people make sense of them. Such cultural factors may increase or reduce the ability of the individual to cope with adverse circumstances. That is why the ascendancy of the cult of the victim runs in parallel with the lowering of expectations about human resilience and competence. The consequent diminution of the meaning of personhood leads to the accentuates human frailty and vulnerability. As I noted elsewhere even feeling ill becomes normal when so much of people’s experience is framed from the perspective of vulnerability[xx].

In all but name the culture of victimhood is symptomatic of the radical transformation of personhood. Our perception of what a person is and what people should be expected to accomplish has altered to the point that we expect the majority of society to be susceptible to mental illness. Children are often ascribed the identity of vulnerability and even growing up is often regarded as a potentially victimising experience.

In effect western society has inadvertently adopted the practice of cultivating the consciousness of vulnerability among the young. That is one important reason why liberating society from its addiction to the possession of a victim identity is so important for the future of humanity.

In Part Two of this essay, we shall explore how the responsibility for the politicisation of the victim was in the first instance the accomplishment of conservative claims-makers who provided a cultural orientation that was enthusiastically appropriated by the American left.

[i] https://www.hackneygazette.co.uk/things-to-do/national/25795044.class-protected-characteristic-arts-world-posh-report-says/

[ii] https://www.oed.com/search/advanced/HistoricalThesaurus?textTermText0=victim&dateOfUseFirstUse=true&page=1&sortOption=AZ

[iii]Weed, F.J.(1995) Certainty of Justice; Reform in the Crime Victim Movement,(Aldine De Gruyter:New York). p.34.

[iv]The Times, 10 March 1998.

[v]See Berrick, J.D. & Gilbert, N.(1991) With the Best Of Intentions: The Child Sexual Abuse Prevention Movement, (The Guilford Press:New York). pp.16-17 and Jenkins, P.(1992) Intimate Enemies,Moral Panics in ContemporaryGreat Britain, (Aldine de Gruyter: New York).p.130.

[vi]This is the clame made by Emilio Viano, one of the leading publicist of victimology. Viano, E.C.(1990) The Victimology Handbook; Research Findings, Treatment, and Policy, (Garland Publishing : New York).p.xi.

[vii]Weed(1995) p.129.

[viii] Best, J.(1997) ‘Victimization and the Victim Industry’, Society, vol. 34, no.4.

p.122.

[ix]E.A. Fattah, ‘Toward a Victim Policy Aimed at Healing, Not Suffering’ in, Davis, R.C., Lurigio, A.J., Skogan, W.J. eds.(1997) Victims Of Crime, (Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, Cal.).p.260.

[x]E. Fattah, ‘The Need for a Critical Victimology’, in Fattah, E.A. ed.(1992) Towards A Critical Victimology Towards, (New York: St. Martin”s Press), p.3

[xi] Furedi, F. (2002) Culture of Fear: the Morality of Low Expectations, Continuum : London.

[xii] See for example ‘depressed men “turn to drink”; silent suffering: concern over ignored illness’, The Independent; 24 April 1996.

[xiii] See for example The Observer, November 9, 2003 “Dangerous pursuit of beauty: The medias notion that thinness is next to godliness plays havoc with vulnerable young minds”

[xiv] See One law for the rich, one for the vulnerable’ in The Independent; 23 March 1993.

[xv] New York Times, January 12 1998“Is Big Brother Watching? Why Would He Bother?; We’re all Vulnerable”

[xvi]These arguments are further developed in Furedi(2002).

[xvii] https://edition.cnn.com/2026/01/27/science/doomsday-clock-2026-time-wellness

[xviii] https://edition.cnn.com/2026/01/27/science/doomsday-clock-2026-time-wellness

[xix] Furedi, F. (2002) Therapy Culture: Cultivating Vulnerability In An Anxious Age.

[xx] Furedi (2002)

This article (On the industrialization of victim culture) was created and published by Frank Furedi and is republished here under “Fair Use”

••••

The Liberty Beacon Project is now expanding at a near exponential rate, and for this we are grateful and excited! But we must also be practical. For 7 years we have not asked for any donations, and have built this project with our own funds as we grew. We are now experiencing ever increasing growing pains due to the large number of websites and projects we represent. So we have just installed donation buttons on our websites and ask that you consider this when you visit them. Nothing is too small. We thank you for all your support and your considerations … (TLB)

••••

Comment Policy: As a privately owned web site, we reserve the right to remove comments that contain spam, advertising, vulgarity, threats of violence, racism, or personal/abusive attacks on other users. This also applies to trolling, the use of more than one alias, or just intentional mischief. Enforcement of this policy is at the discretion of this websites administrators. Repeat offenders may be blocked or permanently banned without prior warning.

••••

Disclaimer: TLB websites contain copyrighted material the use of which has not always been specifically authorized by the copyright owner. We are making such material available to our readers under the provisions of “fair use” in an effort to advance a better understanding of political, health, economic and social issues. The material on this site is distributed without profit to those who have expressed a prior interest in receiving it for research and educational purposes. If you wish to use copyrighted material for purposes other than “fair use” you must request permission from the copyright owner.

••••

Disclaimer: The information and opinions shared are for informational purposes only including, but not limited to, text, graphics, images and other material are not intended as medical advice or instruction. Nothing mentioned is intended to be a substitute for professional medical advice, diagnosis or treatment.

Disclaimer: The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of The Liberty Beacon Project.

Leave a Reply