Nothing to do with either law or justice

Extrajudicial execution in the Yookay

DAVID MCGROGAN

Let me conclude then…that since men love at their own pleasure and fear at the pleasure of the prince, the wise prince should build his foundation on that which is his own.

Machiavelli, from The Prince (Ch. XVII)

Entirely predictably, as the British regime sees its authority diminishing before its very eyes, it is growing increasingly authoritarian. We are governed by something like the love child of Homer Simpson and Baby Doc Duvalier; unable to generate consent through being respected, the regime’s reflex is increasingly to send us to our bedrooms without any supper. There is a deeply pathetic and unintentionally humorous element to all of this, but that’s before you consider how it plays out in detail, and at that level it starts to get nasty.

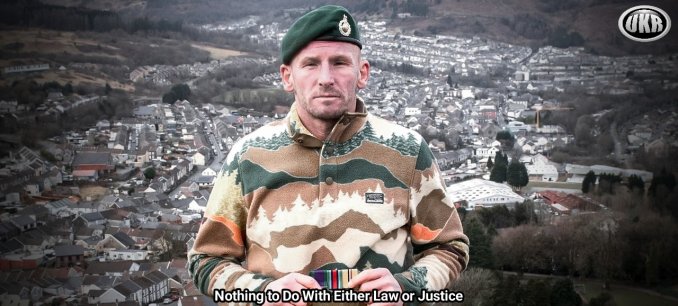

One recent case illustrates how sinister this new mode of governance is quite neatly. Jamie Michael, a veteran of the Royal Marines, was caught in Sir Keir Starmer’s net last year when making a social media video protesting about illegal migration in the aftermath of the Southport massacre. He was acquited of stirring up racial hatred by the jury in his trial within 17 minutes – it was patently evident that he was not guilty of the offence – but has now discovered that what cannot be achieved by law will be achieved by other means. The safeguarding board of his local council (Labour-run, of course) has decided – after a secret procedure – that it is not safe for him to work with children, which includes coaching the local girls’ football team as he was previously doing. This is because a ‘child protection concern’ was raised about him anonymously, and the board decided (to reiterate: behind closed doors) that this concern was ‘substantiated’. The nature of this ‘concern’ would appear to be that Mr Michael has ‘radical and racial views’.

This sounds petty, but the impacts of course are profound. For one thing, Mr Michael’s daughter plays on the team which he is now prohibited from coaching on the grounds of his ‘radical and racial views’. But setting that to one side, as Mr Michael himself puts it:

It’s a horrible feeling to have to tell people I am banned from coaching a girls’ football team. What comes to people’s minds is that I must be a pervert or I’ve done something violent to children.

And one can readily imagine the effects of all this on a man who has been – let’s call a spade a spade – made subject to an extrajudicial punishment. Extrajudicial punishments are supposed to be the last resort of tyrannies. Yet we see them becoming routine in the UK in 2025 (with Non-Crime Hate Incidents being perhaps the most notorious example). What is going on?

In a 1988 article called ‘Machiavelli and the Modern Executive’, the American political theorist Harvey Mansfield provides us with a useful way to understand this. Mansfield is a Straussian and, in that vein, presents Machiavelli to us as what Strauss called ‘a teacher of evil’. And one of the features of Machiavelli’s thinking, as a teacher of evil, according to Mansfield, is that he concluded that ‘tyranny is necessary to good government’.

This is explained by reference to what Mansfield calls ‘the problem of law’, well known to legal philosophy, but cast here in an interesting way. Law, Mansfield points out, ‘cannot attain what it attempts’. To make the crushingly obvious point, a law prohibiting murder, say, does not eliminate murder – laws are not perfectly enforceable. To make an only slightly less crushingly obvious point, people circumvent laws and frustrate the designs of the legislator (consider the black market in cigarettes).

But, more subtly, the problem with laws is that they consist of rules, and the point of rules is that they are not flexible and also require interpretation in hard cases. To use the hoary old example learned by generations of law students in jurisprudence classes, the rule ‘No Vehicles in the Park’ placed on a sign at a park entrance cannot be straightforwardly applied, since the meaning of ‘vehicle’ is not fixed. Anybody would know that cars or motorcycles would fall foul of the rule, but what about prams? Scooters? Children’s tricycles? Adults’ bikes? And what about a real life WWII tank which somebody wants to install in the park as a monument? We all want the rule not to apply in those instances. But we have a very hard time explaining why the rule ‘No Vehicles in the Park’ doesn’t cover them as a matter of principle, without resorting ultimately to, ‘Yeah, but you know what I mean’ (an argument that does not always seem persuasive in court).

Law is, then, as Mansfield puts it, ‘too universal to be rational’. It says to everyone, ‘you are treated the same as everybody else’. Nobody may bring a vehicle into the park. But treating everybody the same as everybody else produces irrationality: cars and children’s tricycles should not be treated in the same way by the rule ‘No Vehicles in the Park’.

Law, then, needs ‘outside assistance’ to be made rational. In the case of ‘No Vehicles in the Park’ that outside assistance comes in the form of common sense, and few would dispute its application in that context. But in real world hard cases, it is felt to need a better justification than that.

One solution, as Mansfield goes on, is Aristotle’s kingship, a concept which still informed thinking two thousand years after the latter’s death. Law’s irrationality can be superseded if it could be shown that it is possible for there to be a good and wise king who is imbued with virtue which enables him to depart from law in accordance with natural right. This, though, was doubtful even to Aristotle. Could there be such a king? Machiavelli presents us with another solution: execution.

This has a double-edged meaning. On the one hand execution is the act of an executive – it is the decisions the executive makes. And, sure enough, this is the origin of modern executive power as we understand it. Modern law delegates power to the executive to make decisions exercising discretion, so as to ensure that the irrationality of law’s universality is remedied. A good example are the UK Home Secretary’s powers, granted by the Immigration Act 1971, to deport non-British citizens whose presence is ‘not conducive to the public good’. The law, consisting of rules, could not in itself embody a rational system for definitively determining when a person’s presence in the country is not desirable on ‘public good’ grounds. No legislator could provide a code comprehensive and detailed enough. The law needs ‘outside assistance’, and that outside assistance is provided by the executive.

But on the other hand, Machiavelli was a fan of execution in the good old-fashioned sense. He was a fan of killing people, in other words, publicly and spectacularly, so as to ‘compel obedience to the law’. And these executions, he said, should be ‘excessive and notable’ so as to instil ‘terror’. More importantly than that, even, they should be extrajudicial. The legal execution is not enough – executions must be carried out outside of the law. They must be purely political and not legal. As Mansfield puts it, ‘the law must accept the help of illegality to secure its enforcement.’

The reason for this is not difficult to see, and it springs from the same origin as the first meaning of ‘execution’, i.e. acts of the executive. The executive acts to remedy the irrationality of law. This might come in the form of swift discretionary decision-making to supplement the law where it is not equipped to satisfy reason. But such swift discretionary decision-making might very well come in the form of public displays of naked power designed to make sure that the population retain their loyalty when law in itself is insufficient to achieve that end.

Although Mansfield does not put it in this way, then, Machiavelli’s prince is both executor and executioner. But these are tied together, and come about in what Strauss identified as a dissonance between law and justice. Strauss said that tyranny becomes ‘morally possible’ in that dissonance, and it now becomes obvious why. Where law is not capable of realising justice, executive power – unconstrained executive power, working above (or below) law – does so instead. The question is simply how ‘justice’ is being deployed to promote the interests of the prince himself. He acts tyrannically in the name of justice, but it is justice as he chooses to define it.

The public execution, carried out extrajudicially, realise’s the prince’s justice through the tried and tested mechanism of fear. And Mansfield draws from Machiavelli’s work a number of themes which inform how such public executions ideally function. Three of these are at the forefront of our minds when reading of cases such as Jamie Michael’s.

First, the extrajudicial or political execution is indirect. For Machiavelli, most people do not wish to themselves rule, but nor do they like the feeling of being ruled. The wise ruler, then, does his best in ordinary times to conceal from the people the fact that they are being ruled. He tries his best to make them govern themselves in such a way that they will do as he wishes, through trickery and lies. Here, of course, is the origin of propaganda; here is the origin of the modern spin doctor; here is the origin of the ‘nudge’.

But here also is the origin of the public execution: indirectness is not the same as total invisibility. There are times when the ruler needs to make an impression, so that the people do not entirely forget about him. And sensational public executions impress the people by punishing the ‘insolent’ and serving as brief moments in which to remind people that the ruler rules. In this way, the deceitful, disguised, indirectness of modern politics is supplemented by the spectacular extrajudicial execution – the two complement one another. This stands in comparison to the understanding of the ancients that power should always display itself openly, publicly, and honestly, and that executions should therefore only be carried out in accordance with law.

It follows from this, second, that executions should be sudden. They should happen at a stroke. Through their suddenness, they remind the people that nothing is to be taken for granted. And the people therefore remember that they cannot simply rely on things being as they are. Quoting Mansfield directly:

By an impressive stroke the prince thus renews his authority and makes himself a new prince. His personal power, instead of disappearing into the regularity of his laws and ordinary methods, becomes visible; his actions, if sufficiently ambitious, can achieve ‘the greatness in themselves’ that silences criticism.

The executor cuts through formalities in carrying out the extrajudicial execution. And this shows the people that they need to be on their toes. They live at the sufferance of the prince, and hence are reliant on him. What the prince can take away, he also gives; the suddenness of his decision-making reveals his necessity.

And it follows from this, third, that the decision to execute must be made secretly. The result of the execution is spectacular – it should be put on display for all to see. But the process is properly ‘utterly illegal’ and therefore the decision-making is not on view. It must be conspiratorial, because for Machiavelli conspiracy underlies all of politics. And therefore it must be hidden knowledge until the conspiracy is complete and the moment of realisation – the moment of execution in all senses – comes.

Nowadays we are squeamish about killing and we have prohibited even judicial execution in the UK. But that does not mean that the prince has lost the capacity to instil fear. It is just that it is people’s reputations which are murdered, rather than their physical persons. And the extrajudicial killing of reputations is becoming quite the industry here these days.

You will of course have noted that every aspect of Jamie Michael’s case is laid out here in Mansfield’s exegesis of Machiavelli’s texts. You will have noted that the execution of his reputation was sudden and secretive, not to mention conspiratorial (taking place behind closed doors, and offering him no opportunity to defend himself, know his accuser, or even know that the procedure was taking place). You will have noted how this punishment of his ‘insolence’, in professing the wrong opinions and yet walking free from trial (which is worse) serves as a public spectacle, to remind people that the velvet glove our regime wears conceals an iron first. And you will have noted how a concrete reminder of this kind supplements and reinforces the ordinarily indirect, deceitful and disguised way in which our regime typically operates.

But you will also have noted the overarching point, which is that, to Machiavelli, and to our own regime, it is the failure of law to achieve rationality or justice that necessitates the execution. The workings of law – ‘you will be treated the same way as everybody else’ – acquitted Jamie Michael and revealed the Crown Prosecution Service to be an ass. This, though, was not justice in the eyes of the regime. It may have been the workings of law, but it was not the working of reason. Reason dictated Mr Michael should be punished. And so he must: where there is a gap between law and justice, ‘properly’ understood, tyranny must come along and patch things up. The extrajudicial, political punishment naturally follows the failure of law.

Looking at things in this way will unsettle you, as it should. It did not used to be necessary to think like this in Britain. Nowadays it is. And the reason for it is more unsettling yet. As Mansfield was keen to point out, Machiavelli made virtù or ‘virtue’ the defining characteristic of a good ruler. But his virtue was not the virtue of Aristotle. It was not virtue in the sense of acting in the interests of the right order of things. For Machiavelli, ‘virtue’ simply meant doing what was necessary to rule. It was something more akin to virtuosity than classical virtue. And it seems evident that for all that the members of our regime like to signal virtue, as the saying nowadays goes, their understanding of virtue is much, much closer to that of Machiavelli than of Aristotle. Their virtue is not that of the ruler who seeks right order. Their virtue is that of the ruler who seeks to continue to rule. That is their philosophy; that is their goal; that is their desire; that is what they are for. They perpetuate their regime and that is that.

It is important then to ask ourselves two questions. The first is why it is that we got into this predicament. How is it that we have a ruling class who consider virtue to be synonymous with necessity, and who therefore consider tyranny to be necessary for good government? What have we lost that we might once again gain?

The second is, how bad can things get? No, we should not exaggerate: nobody is being dropped from helicopters into the ocean; nobody is being sent to mine for uranium in Siberia on starvation rations; nobody is being tortured by the police in their own homes. Yet at the same time we should not be naive. We inhabit a society now ruled by a regime which sees no problem in principle with extrajudicial, political punishment. It is a regime which, with Machiavelli, considers tyranny to be necessary for good government. Reflecting on this may serve to focus minds for what will unfold in the coming years. We should not shy away from this or stop talking about it for fear of being labelled with the usual labels.

You can donate to support Jamie Michael’s legal challenge to the decision to bar him from working with children here.

This article (Nothing to do with either law or justice) was created and published by News from Uncibal and is republished here under “Fair Use”

Leave a Reply