Non-compliance

What we can learn from the past and what we must do for ourselves

ALEX KLAUSHOFER

We are entering new territory in Britain.

Events around the Budget illustrate the depth of the governance crisis the country is in. It turned out that the “black holes” which justified the exceptional tax rises of the last two years did not exist. The news, which came via the Office for Budget Responsibility, meant that the government lied to the people in order to take more money from them.

In the wider world, this is understood as fraud; in public office it is malfeasance and Misconduct in Public Office. Not very long ago, the affair would have resulted in ministerial resignation(s) and possibly the voiding of the Budget.

Instead, the cries for resignation abated. The whistleblower, in the former of OBR chair Richard Hughes, lost his head. MPs voted the farmers’ tax and other Budget measures into law. (You can find out how your MP voted here.) Subsequently, the “U-turn” on inheritance tax notwithstanding, it’s been dawning on many in the Establishment that the government is simply not listening.

When the government won’t listen, what do you do?

The Budget involved another deception which affects us all. The threat is both under-recognised and quite urgent, so I’m going to do a short update about it in a separate Substack early in the New Year.

Meanwhile, a suite of recent announcements make it clear that the government is proceeding with its own society-reshaping plans regardless of the will of the people. I’ll briefly highlight just three:

Digital ID. The government has said it plans to introduce mandatory digital ID by 2029. The proposal is difficult to report on because it hasn’t announced any details of exactly how it would work, but all those following the issue closely agree that what is envisaged is the creation of a centralised database linking large amounts of personal information. It would give those running it the power to withhold access to services : you’ll find the best explainer of the implications here. Compulsory digital ID is already being introduced by stealth via the government’s One Login platform about which, thanks to revelations from a civil service whistleblower, there are major security concerns.

The scrapping of jury trials. The government’s plan to abolish juries except for the most serious crimes would result in many citizens being tried by a single officer of the state. The 800-year-old system of trial by jury is a cornerstone of British democracy which, the barrister Steven Barrett argues, is as important as the right to vote.

The introduction of nationwide facial recognition. The police have been using facial recognition in cities such as London and Cardiff for some time and recently the Home Office has provided police forces elsewhere with camera-fitted vans so that surveillance can be expanded. In December, the government launched a consultation on a national legal framework for the use of facial recognition so that police can be “confident” in using it in every town, city and village. It is seeking public consent for Parliament to pass laws authorising emerging technologies, including that which predicts behaviour by reading emotions. Having been through the consultation to prepare guideline responses for Together, I can assure you that this is scary stuff indeed.

Each of the above should set off alarm bells for two reasons. Firstly, they are all things which are prima facie inconsistent with a free society, giving the state unprecedented levels of control over daily life, introducing the mass surveillance of an innocent population and creating judicial arrangements ripe for the abuse of power. A liberal democracy is supposed to afford continuous protection for foundational rights regardless of which political party is elected into power; any changes the government makes must respect, not override, those basic rights.

When an oppressive system is being imposed from the top, what do you do?

Of course, it could be argued that time can bring the need for change. When big changes are envisaged, a society which takes rule by the people seriously embarks on a process of reflection and discussion, both to fully understand their implications and determine whether there is genuine public consent. If widespread consensus for change emerges, lawmakers then embark on a lengthy process involving plenty of scrutiny. As part of this process, the governing party should have secured consent for major changes by making clear its intentions during the election campaign.

None of the above – compulsory digital ID, mass surveillance or the collapse of the judiciary into the executive – featured in the government’s manifesto. This is the second reason why alarm bells should be ringing for anyone who doesn’t fancy living under autocratic rule. For if a government can introduce way-of-life-ending measures simply by dint of holding office, elections are meaningless. If no democratic mandate for change is required, if there are no effective checks and balances within the system, elections become mere performance and display. Many of the world’s dictators hold periodic elections.

That reminds me: the government is also encouraging councils to delay local elections.

When democracy is failing and an authoritarian takeover is underway, what do you do?

These are genuine questions, examples of real asking, born of not-knowing what the solution is. Non-compliance begins when the usual means of addressing a problem have been exhausted, when the remedies within a system have failed. It begins from the absence of answers, a throwing up of the hands – what do we do?

In our personal lives, we all recognise this moment. Something unexpected happens and you simply don’t know what to do. Perhaps you sit down and stare into space for a while. Perhaps you go about your business in a daze for days, weeks, months. And then a solution, or at least a way forward, emerges and you’re out of the void.

These days, when the problem extends way beyond the personal, getting out of the void involves a painful renegotiation with reality. We must come to see things as they are rather than what we believed or hoped them to be. If, after a successful process of seeing, we don’t collapse into hopelessness, a spirit arises which says something like: “this is wrong. I will not comply”. And out of that comes a determination to take a position, to act, even though you might not yet know what to do.

The animating spirit of non-compliance and its active, public variant of civil disobedience is expressed most eloquently by Martin Luther King in his Letter from Birmingham Jail: “One has not only a legal but a moral responsibility to obey just laws. Conversely, one has a moral responsibility to disobey unjust laws.” This kind of clarity about what’s wrong, linked to a sense of possibility that things could be made right, is a pre-condition for non-compliance. Once you have that clarity, you’re halfway there. The question “what do we do?” may be asked again, but it’s at a new level. It’s now a practical question, one that seeks to discern the most effective course of action.

It’s striking how far twenty-first century Britain, along with other Western nations, has lost this spirit. Mainstream society seems to have forgotten both the idea of the power of the people in its old, primordial form, and that the defining feature of modern society is supposed to be self-governance. Instead, there’s been a reversion into passivity, in which many seem to see themselves as subject to powerful forces and leaders over which they have no influence at all. Many modern people have become “victims”.

Contrast this with the recent resignation of the government in Bulgaria after tens of thousands of people took to the streets – I bet they didn’t ask the police for permission to gather. The protests were triggered by a tax-raising Budget: “Many saw the move as taking money from ordinary people in a power grab,” reported The New York Times.

Current attitudes to non-compliance

Let’s take a closer look at where we are.

With the caveat that there’s a minority with some sophisticated ideas about non-compliance, mainstream Britain is in the grip of what I call “the compliance fallacy”.

This is the idea that the safest approach is to go along with new and overbearing demands from the authorities. You might not want to have a smart meter/undergo age verification/give your biometrics but, the thinking goes, doing so will not make any difference. “It’s just” is the byword of this attitude. By complying with “just” another thing, you will stay out of trouble and life will go on, more or less, as usual.

Therein lies the fallacy. Because when a takeover is in progress, it’s only a matter of time before your life and that of those around you changes beyond all recognition. All the “justs” add up to a very unpleasant whole, leaving some bemused and asking “how did we get here?”.

The answer is: step by step. The authoritarian rulers of history took power through a series of strategic steps, each advancing them towards their goal of control. Some such as Franco first took power with a military coup and went to consolidate it with censorship, surveillance and political repression. Other dictators worked within democratic systems: Hitler spent years creating the conditions in which people would elect him as leader of the country. Pre-Nazi Germany bears some uncomfortable similarities to contemporary Britain: an educated population, large welfare state, high taxes and an increasingly regulated private sector. The common factor in the growth of autocratic power is the willingness of people to take each step, either failing to see it for what it is – “digital ID is just convenient” – or dismissing the significance of their choices – “it makes no difference what I do, it will happen anyway”.

Maintaining the compliance fallacy in the face of mounting evidence that a power grab is underway requires a curtailed kind of seeing in which the attention is focused on the immediate and partial. The bigger picture, both the implications for wider society and likely future consequences, is ignored. As such, it’s part of the denial to which humans, as Stanley Cohen illustrates in his definitive book on the subject, are so prone. It’s also an expression of the inner powerlessness and sense of isolation that comes from the story of separation many Westerners have internalised.

Once we see ourselves as separate from others, we readily believe our actions don’t matter. Faced with another demand from the top, we may say things like “I can’t” (refuse) or “I have to” (comply). When this mindset prevails, there is a relationship that looms large: the one with the authorities. In its fullest expression, the separated individual’s relationship with the state can become so consuming that it overrides all others, enabling the betrayals of spouses, siblings and neighbour that characterise modern dictatorships.

Over my adult life, I’ve watched the development of an increasingly complex, regulated state giving corporations more and more power. Functions have become intertwined, with private companies providing essential services and enforcing new government regulations. As a result, financial institutions, utility companies and Big Tech now see us less as customers than as a population to be managed. They expect large amounts of personal information, access to our bank accounts and the right to raise prices dramatically. We’re now at the point where energy companies can break into people’s homes without due process.

Faced with such organisations, people often feel powerless. They feel they “have to” spend hours negotiating automated phone systems and sign up for direct debits (both only introduced only in the past couple of decades) or agree to the installation of a smart meter, a new imposition whose consequences most people have yet to fathom.

This powerlessness derives from a partial or distorted picture. Pan out from the individual “just” taking a single step, and a wider lens reveals an entire demographic, a whole society all walking in the same direction. This cuts both ways: we can use this insight to walk in a different direction, or we can carry on complying. The belief in our own powerlessness can be self-fulfilling.

As 2025 becomes 2026, it’s clear that many of those who understand that Britain is at a fork in the road – free society or technocracy? – remain in the grip of the compliance fallacy.

Since the announcement about mandatory digital ID, I’ve been surprised by the number of people crying “what do we do?” in a way that lacks the genuine asking I referred to earlier. These cries are more of a wail, an asking to be rescued. Ironically, they often come from those who saw the origins of our current predicament back in 2020, people you’d think might have developed some ideas of their own. Instead, the criers enjoin social media influencers for workarounds and painless remedies in tones that sound desperate or entitled.

This, too, is part of the compliance fallacy, a cluster of beliefs and expectations that i) there exists some kind of template which can be applied to our current situation, ii) that leaders (broadly understood) have privileged access to solutions and iii) that implementing recommended solutions will cost nothing.

The good news is that we can get beyond this learned helplessness and rediscover the psycho-social sources of non-compliance. In Britain we don’t need to look far.

Britain’s noble history of non-compliance

Britain has a long, rich tradition of non-compliance that helped to create the freedom for which, until recently, the country was famous.

It’s no coincidence that historical movements for freedom and social justice were rooted in religion and spirituality. Much of our current helplessness is bound up with a failure to think beyond the here and now. Despite all our exposure to other ways of life through education and travel, we seem to be mired in the “isness” of things, and lack the capacity to envision. Religious and spiritual traditions have this in spades, providing an alternative point of perspective – and a source of authority higher than power-hungry humans.

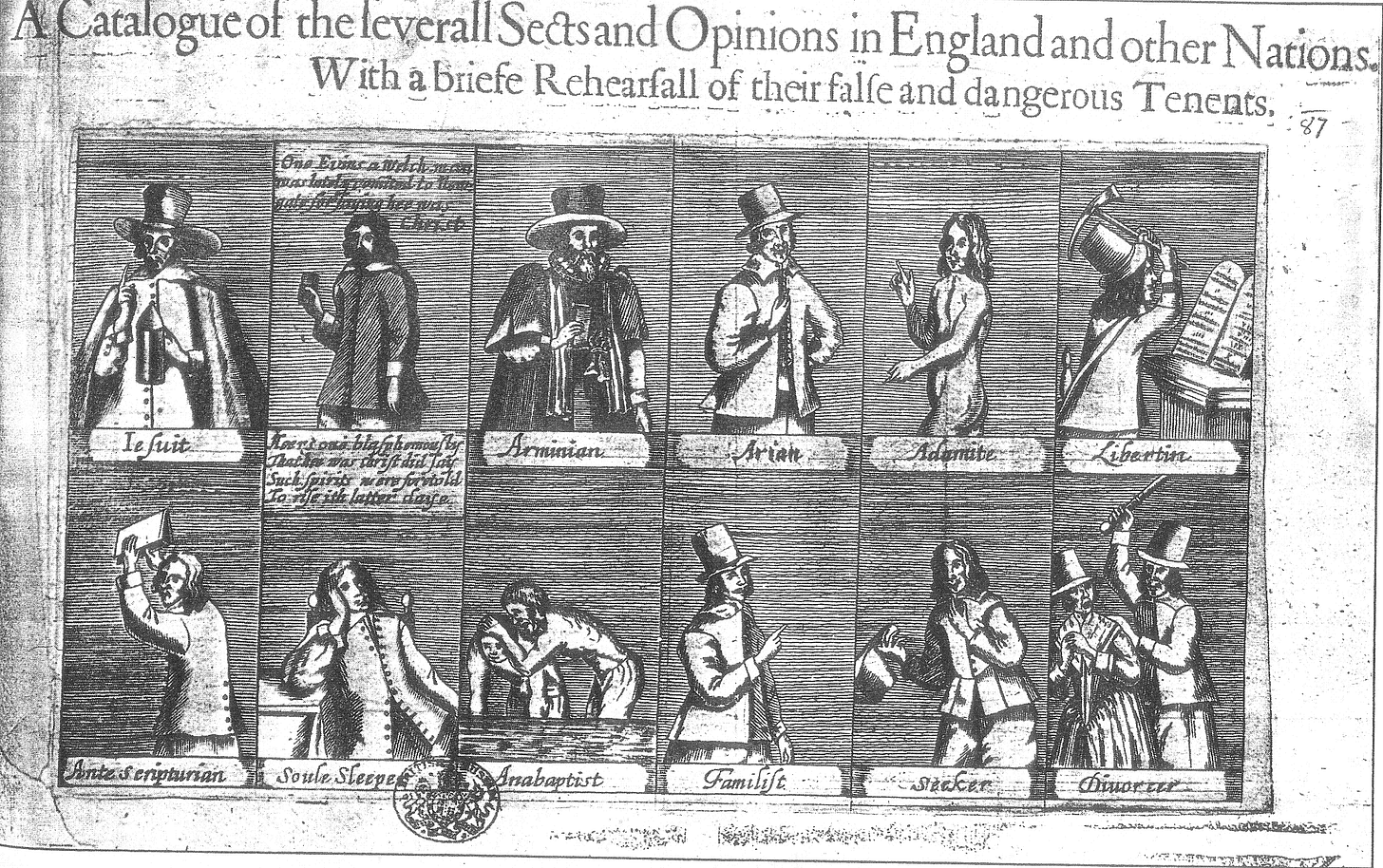

Britain’s age of religious dissent began in the reign of Elizabeth I with Protestant discontent with the Church of England. Puritans wanted to reform it, Separatists to break away entirely, while the monarch saw conformity as vital to maintaining political authority. A series of Acts of Uniformity aimed to standardise worship and suppress religious dissent, but the final one in 1662 only served to consolidate the divide between orthodox and dissenting Christians. The Great Ejection, expelling two thousand priests from the established church, led to the creation of independent religious communities, fostering “congregationalism”, the movement of self-governing congregations. Over the following two centuries nonconformity flourished in England and Wales: Congregationalists and Unitarians, Methodists and Quakers had their own chapels and meeting houses and, banned from the universities which were the gateway to successful careers, developed their own, parallel education systems.

By the early nineteenth century, nonconformists and Anglicans inhabited almost completely separate worlds, with nonconformists maintaining their own communities in the larger cities. Their existence demonstrated that it was possible to live outside the mainstream, and that the power of the authorities was limited. According to David M Thompson in Nonconformity in the Nineteenth Century, “nonconformity was largely responsible for the freedom of religion and the freedom of thought enjoyed in nineteenth-century Britain. This established a tradition in which political liberty itself flourished.” Nonconformity fostered resilience and an active approach to life, and many nonconformists were philanthropists and social reformers. “It is practically impossible to be an uncommitted or casual Nonconformist,” he continues. “This commitment was also carried over to a commitment to live one’s religion in everyday life. For some, this meant social action; for others it meant political action.”

This vibrant aspect of Britain’s history is alive to me because the English side of my family descends from a long line of nonconformists, documented in my great-grandmother’s biography of her father, a Victorian philanthropist who helped to found the public library movement. A self-made businessman, Thomas Greenwood lived in London’s nonconformist community of Stoke Newington but his origins were humble. As a yeoman farmer in the north, his father had been part of the Chartist movement while documents found in the farmhouse testified to a history of dissenting ancestors. They went back to one John Greenwood, hung at Tyburn in 1593 for “devising and circulating seditious books” – one of the founders of English Separatism.

I find this truly inspirational. Sometimes I can almost feel a line of souls/awkward humans standing behind me, defying Authority in different ways. But the times we are now in demand more than pleasant feelings. If I pay proper attention to the lessons of my forebears, I can derive some practical wisdom: don’t expect everything to come right quickly which translates into: Keep Going No Matter What. Britain’s multi-century tradition of nonconformity had many twists and turns, and there were plenty of disagreements and divisions among the various denominations. Our wayshowing nonconformists were united in one respect only: they didn’t accept that the state should tell them how to live.

Modern non-compliance movements

Can we learn anything from more recent movements that championed more specific causes?

I think we can.

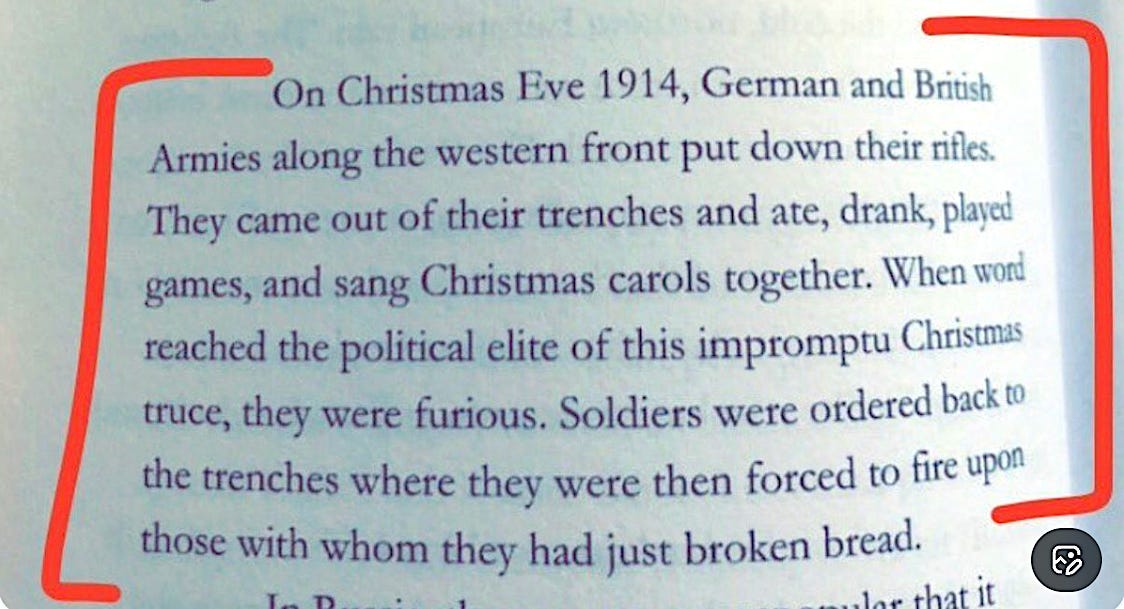

The conscientious objectors of the First World War left a legacy disproportionate to the 16,000 men on record for refusing to fight, a tiny number compared to the six million who served in the British Army over the course of the conflict. History tends to present them as going against the grain of everything that mainstream society held dear: love of country, doing the right thing and being brave. It’s a view which disregards the fact that this was the first time a British government had imposed compulsory military service, a demand which tacitly expressed the idea that the citizen belongs to the state. Conscription was only introduced in 1916 because so many of the willing recruits had already been killed. In this light, the expectation that a young man should go to his likely death because the state told him to looks quite unreasonable.

The failure of wider society to recognise this truth is testament to the power of propaganda. Local tribunals willingly condemned conscientious objectors to prison, hard labour and execution at the frontline, illustrating how quickly a new idea can become social orthodoxy, especially in the face of A Threat.

The conscientious objectors knew something the majority didn’t. The word “conscience” derives from “con”, which means “with or together”, and “science” whose etymological root is “scire” meaning “to know”. Con-science means “with knowing”. Objectors’ stated reasons for refusing to fight took a variety of forms: some were religious, and a significant proportion were Quakers, acting out of a deeply-held commitment to pacifism. Others objected to killing on non-religious grounds and a large proportion saw the war as a political operation in which rulers were sacrificing ordinary people to their power games.

The lesson here is that an effective non-compliance movement doesn’t have to be composed of people who share the same perspective. Conscientious objectors had different reasons for their stance; what united them was their refusal to fight. For some, that “no” was based on an abstract principle, conceived in political or religious terms; for others it would have been experienced more as the “knowing” of intuition. Since the situation they found themselves in was unprecedented, they had to trust this knowing, placing it above the dictates of both Authority and Society.

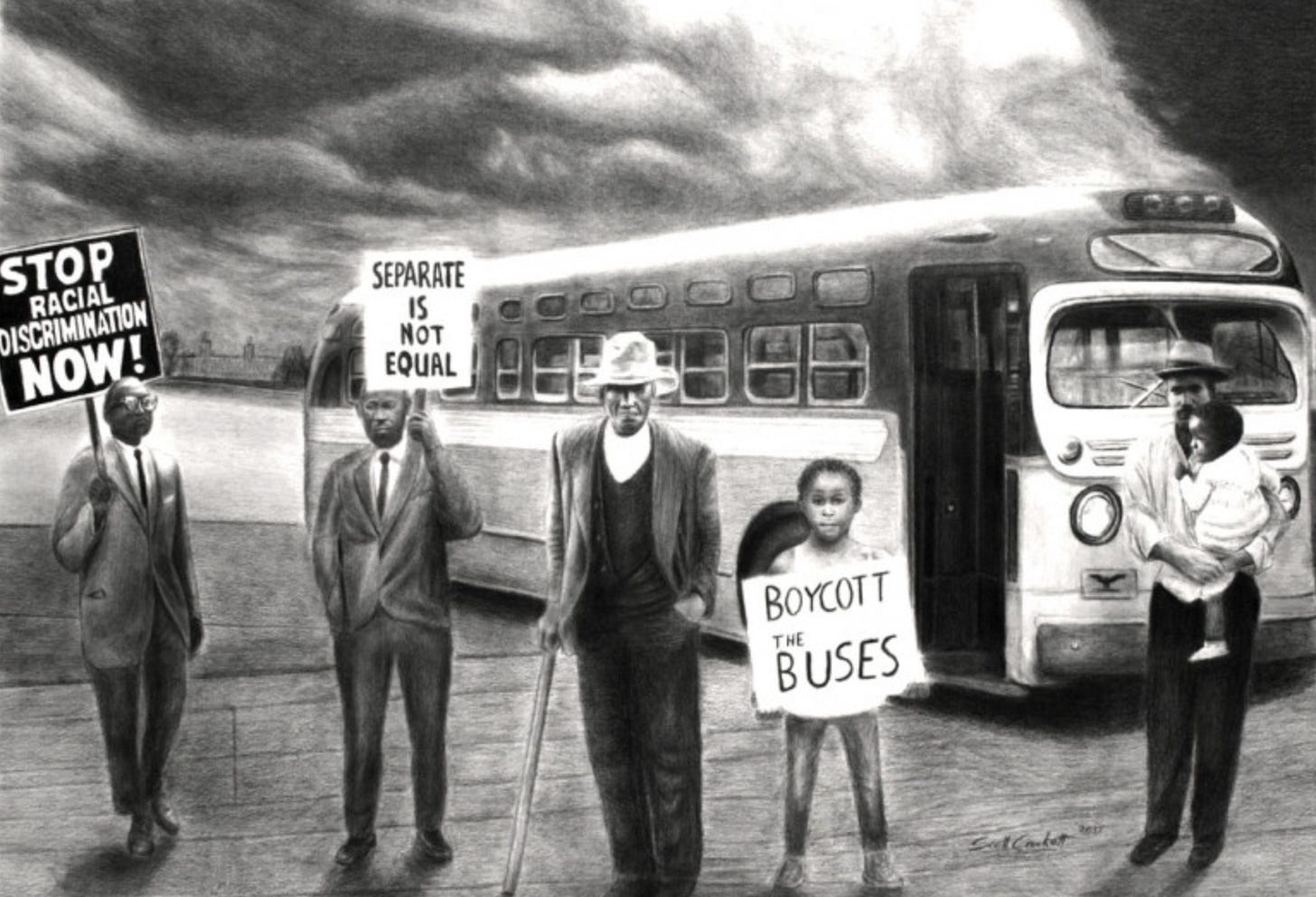

The bus boycott led by Martin Luther King in 1955 in Montgomery, Alabama that brought an end to segregation on the city’s buses is a landmark example of successful non-compliance. The ethos of the year-long protest evolved out of King’s Christianity and wide reading which included Thoreau’s essay “Civil Disobedience”. King was also inspired by Gandhi and characterised the boycott as “an act of massive noncooperation” based on the principles of nonviolence and passive resistance. “While the nonviolent register is passive in the sense that he is not physically aggressive towards his opponent, his mind and emotions are always active,” he wrote in his memoir Stride Toward Freedom: “It is active nonviolent resistance to evil”.

Reading King’s account of the boycott, I was struck by a number of things. The first is that it was started by the quiet, spontaneous act of non-compliance of a single person, Rosa Parks, arrested for refusing to give up her seat to a white man. From there, events had their own momentum and within a few days a boycott of almost complete non-compliance was organised. The buses were empty and people found other means to get to work, sharing lifts, taking cabs, walking and riding donkeys. As King put it: “The once dormant and quiescent Negro community was now fully awake”.

But behind the spontaneity, the pre-conditions for successful organisation were established. The realities of segregation and the religious nature of the community made for good communication channels: word spread fast and public meetings were easy to organise. But the following months brought many challenges, largely from the city authorities who used some nasty tactics to quash the boycott, from arresting blacks for minor driving offences to planting a false story in the press that the strike had ended. The movement also had its own internal challenges, when some people became discouraged or contemplated violence. There were many points at which the protest could have collapsed: every key decision arose out of a constellation of individual choices, collective feelings and actions. The successful outcome came only with a ruling from America’s Supreme Court that segregation on the buses was illegal, arriving just as the city authorities were attempting to make car-sharing illegal.

Herein lies the main piece of wisdom the Montgomery Bus Boycott holds for us later observers: arising out of a particular situation, non-compliance has to be enacted afresh each time. There are no blueprints or easy solutions, only a new reality demanding a response, or rather a sustained series of responses, from the humans of the time. There is always jeopardy, always creativity, always discomfort.

Looking at the photos of the Montgomery movement, it struck me how its generative qualities have been absorbed into history, the lessons occluded by the current social consensus that racial discrimination and segregation is wrong.

But we DO have a shared, recent experience in Saying No, one very relevant to our current situation. It’s derived from the extraordinary new demands that were made on us in 2020 and beyond: already forgotten by many, burnt into the psyche of others. For some in this latter group the non-compliance lesson came from mask mandates. For me, in Portugal, the teacher was vaccine passports.

Vaccine passports were imposed one December day, with three days’ notice and without any public or political debate. (I can’t prove it, but I suspect some string had been pulled by the EU.) I’d just moved into a small flat with the intention of spending most of my time elsewhere, but the ban on anyone who didn’t show a Covid certificate extended to most of Lisbon’s indoor spaces. Suddenly cafes and libraries were off-bounds and I was excluded from the social networks of the new expat, including my improv drama group.

So I lay on my bed or sat in the park where, it being southern Europe, it was often warm enough to work. Meanwhile, online meetings revealed that the situation of nonconformists elsewhere was considerably worse than my own: I heard the anguish of a Canadian banned from leaving her country, admired the brave face put on by the French woman who had lost her job and witnessed the teary distress of the German friend admitted nowhere except the grocery store. None of us knew how long this strange limbo would last or if we would have to adjust to lives of permanent exclusion.

Then, as winter wore on, things shifted. In Portugal, I found cafes and bars that would admit me, either because the Kafkaesque government regulations made them exempt or their owners were defying the mandate. I discovered a merry band of revellers who created their own restaurant by hiring a private room and, with another refusenik, set up a new drama group called, rather pointedly, “Improv for ALL”. The beginnings of a parallel society was emerging; this was creative non-compliance. Meanwhile, thanks to a burgeoning black economy in fake vaccine passports, many of the internationals who had come to Lisbon for a good time carried on partying. Eventually, the Portuguese government lifted the mandate, saying it wasn’t being sufficiently enforced.

Around this time, the Austrian government made Covid vaccines mandatory, threatening those who refused to comply with fines. It failed utterly: five weeks later, with almost a third of the population not “fully vaccinated”, the mandate was dropped.

A couple of lessons can be derived from this insalubrious period of our recent history. The first is that NON-COMPLIANCE WORKS. It’s impossible to overstate this obvious, fundamental point: unless most people in a society go along with it, a new system simply can’t be introduced. The accompanying sub-point is worth noting: the clearer a population makes its refusal, the sooner the government will give up because visible, ongoing non-compliance undermines its authority more broadly. An illustration comes from the Portuguese government’s attempt to introduce an 11pm curfew. For a few nights, I went out at 10.50 pm and walked around to add another body to the streets. There were lots of people out and about and the curfew was soon dropped.

A second lesson is that you don’t know what you’re capable of until you find yourself tested. Before Covid, I had no experience in deliberately defying government because I had never felt the need to. In Portugal, my non-compliance started small, with the illicit purchase of underwear. The government had outlawed the sale of goods it deemed “non-essential” with the result that some items in shops were placed behind red and white plastic tape. I had brought few clothes to Lisbon in my one suitcase: how did the Prime Minister know what I needed? A housemate was also short of underwear. I am pleased to report that seven of the eight shops I tried were happy to sell me pants and my shopping expedition felt deliciously transgressive.

Faced with non-sensical, arbitrary restrictions, my attitude towards the law relaxed fast. When, defying an edict to only sell goods in the doorway, a shopkeeper invited me inside, I leapt over the threshold like a dress-seeking kangaroo. Irritated by an 8pm prohibition on alcohol sales in shops, I went straight to a nearby restaurant and bought what I wanted.

Although I didn’t realise it at the time, I was building my non-compliance muscle, getting more comfortable with saying “no”. And so it was that, when the vaccine passport mandate was announced, I knew what I would do, starting with the preparation of some sentences in Portuguese. When I first used one – “Nao mostro documentos para comer” (I don’t show papers to get food) – I heard a gasp from another customer. Then the proprietor nodded and waved me to a table. Every time I used the phrase subsequently – it didn’t always work – my nervous system would jangle for the rest of the day. But when, months later, a new landlord asked for an unnecessary Covid test, I didn’t think twice about my response. Although I badly needed accommodation, refusing what felt wrong had become natural.

I’ve drawn on this experience repeatedly since returning to Britain: No, I’m paying by cash. No, I don’t do WhatsApp. No, you can’t have my biometrics. Saying No has become second nature for the smaller issues. As for the big ones that may lie ahead, who knows?

Herein lies an under-recognised lesson of non-compliance: it’s a matter of individual learning which takes time and practice. This, its human side, cuts both ways: just as you can do more than you ever anticipated, you can’t expect everything of yourself immediately.

Non-doing

I want to acknowledge a form of non-compliance which I think could be really effective and won’t work at all.

The first part of this paradox is best expressed by Penny Kelly, one of the visionary thinkers in the US whose work I’ve been following. She advocates what you could call strategic non-compliance, a conscious and deliberate process developed over time. It is born of “the need to let go of the old world slowly, with care and precision. There are many ways to defeat an old world without getting tangled up in bloody battles using guns and bombs. The key is the strategic withdrawal of attention, money and compliance.”

In other words, you simply stop supporting or doing things that maintain the kind of world you don’t want. In practice, in contemporary Britain this encompasses a vast range of changes from the easy, such as giving up Google or the BBC, to the ultra-challenging, such as refusing to pay taxes or building a new way of life from scratch – see the extraordinary Off-Grid Family. In between lies a plethora of options, from leaving a corporate or public sector job to work for yourself, homeschooling children, growing food and cutting out supermarkets.

Regardless of what particular changes and choices are made, strategic non-compliance requires a pre-condition called Attitude. Attitude says: I don’t like this, I don’t want to support this, I don’t think this is good for people so … what can I do?

While compliance says “I can’t”, non-compliance says “I can”.

The other side of the paradox is organised non-compliance, in which people withdraw their participation from mainstream society for a limited period of time. The idea of what could be called The Great Non-Doing is that large numbers of people stay home, neither working nor buying anything. The point of the exercise is to remind those with power, both government and corporations, that the whole monetised, regulated shebang that is modern life depends on us, the customer-citizens. Withholding our participation would also have a powerful effect on us, acting as a kind of peaceful re-empowerment exercise.

In Britain, a period of organised non-compliance is planned for a week in February with the Great British National Protest.

While I love this idea in principle, I doubt whether enough people in Britain would participate to make an impact. Even the suggestion of a “strike” on social media seems to make some people very angry. The anger takes the form of immediate dismissal, wilful misunderstanding of what is being proposed or outright hostility to anyone advocating such a strategy. This is a symptom of the victim consciousness which underlies the non-compliance fallacy fighting for its survival: like an angry teenager, it doesn’t want to get up, get a job, take on adult responsibilities. In other words, in Britain we’re not ready for this kind of unified action.

But that doesn’t mean that strategic non-doing doesn’t work. It’s happening all the time, as more and more people realise they’re being ripped off, that their health is being compromised, that we’re fast losing the rights it took our ancestors centuries to acquire and being led into a digital system which could cost us our humanity. It’s happening in small ways as people quietly stop doing things it turned out weren’t necessary and it’s happening in big, effortful ways from the minority who are creating alternatives.

A note about Substack

Recently Substack sent me an email saying it is introducing age verification for readers in the UK to comply with the Online Safety Act. It’s not clear exactly how extensive the requirements will be, since many readers will already be verified and the measures only apply to certain features such as accessing DMs.

You probably know this, but I do not want anyone to comply with such measures in order to access Ways of Seeing. Age verification is the beginning of the end of online anonymity and there is plenty of evidence that governments will link it with censorship and digital ID if they can get away with it – Ofcom is already proposing to give itself some very sweeping powers which I’ve written about here. If, in the longer term, things become difficult on Substack, I’ll be looking for another platform to host my work.

Should you be asked to verify your age by Substack, a good VPN connected to an open country should get round that. And I’d be interested to hear about any significant experiences: you can email me directly at alexklaushofer AT protonmail.com.

Resources

Here is a list of things to do to resist digital ID by one of the UK’s principal activists and a clear piece by Iain Davis about non-compliance with digital identity.

Together has drafted a Bill of Digital Rights to ensure that there are always non-digital ways to access essential services.

The Global Nonviolent Action Database has lots of examples of cases and movements the world over.

Beautiful Trouble is a resource with information for planning and organising social action. There’s an accompany book with all sorts of ideas.

This article (Non-compliance) was created and published by Alex Klaushofer and is republished here under “Fair Use”

Leave a Reply