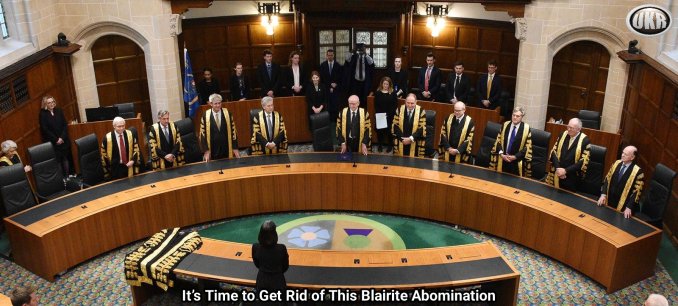

It’s time to get rid of this Blairite abomination

The Supreme Court is the symbol of an undemocratic culture that views judicial authority as superior to elected Parliament

A nation needs a supreme court only if its parliament is subject to a higher legal order. This was the case when Britain was an EU member state.

However, now that we have left the EU, it is only Labour’s incorporation of the European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR) into British law via the Human Rights Act 1998 that still relies on judicial superintendence. Given the growing consensus that Britain should leave the ECHR and repeal the Human Rights Act, now is the time to revisit the judicial architecture built to police an increasingly defunct status quo.

A constitutional court inevitably becomes a political court, and Britain’s Supreme Court is the symbol of an undemocratic culture that has come to view judicial authority as equal, or superior, to that of our elected Parliament.

The doctrine of parliamentary sovereignty has been Britain’s defining constitutional principle since at least the mid-19th century, when it was most clearly enunciated by the renowned constitutional scholar AV Dicey. The principle of parliamentary sovereignty holds that Parliament has an absolute right to make or unmake any law whatsoever, a settlement unchallenged until Britain joined the European Economic Community in 1973.

For a time, Parliament voluntarily submitted to a supreme legal order (EU law) as a term of membership, and creating the Supreme Court was arguably logical to formalise that deference. But with EU membership now firmly in the rear view mirror, and the British electorate increasingly desperate for a system of governance that doesn’t continually do the exact opposite of what it has voted for, it’s time to revisit these arrangements. No court can be supreme over Parliament; giving the Supreme Court the impression that it is encourages overreach.

We haven’t arrived at this status quo overnight. Parliament has conspired with the judiciary to invite this level of interference via a mixture of ideology, constitutional ignorance and poorly-drafted and ill-considered laws. But judges should have no business in quashing the prorogation of Parliament or telling the Government how to assess its obligations under international refugee law.

The doctrine of implied repeal – the idea that if two statutes contradict each other, the more recent one should take precedence – was once used to preserve parliamentary sovereignty. However, even that has been partially cast aside as the courts have struck down parts of the Illegal Migration Act 2023 – which sought to treat small boat arrivals as economic migrants – as inconsistent with human rights protections.

The Left or Right (usually the Left) might cheer on these judgements, and even add a spider brooch to their Twitter bio out of homage to Baroness Hale making Boris Johnson’s life difficult. But making political choices should be a fundamentally uncomfortable place for a British Supreme Court justice to be.

Political choices must be made by elected politicians. We’ve ended up with this dysfunctional constitutional architecture because New Labour vandalised ancient constitutional norms through its hubristic and far-reaching legal reforms.

Leaving the ECHR and repealing the Human Rights Act is – following the Conservatives’ recent announcement – now the consensus on the Right. However, overturning a legal framework that invites endless judicial review of fundamentally political decisions like immigration control is necessary but not sufficient to return power to elected representatives in Parliament. The Constitutional Reform Act 2005, which created the Supreme Court, also references the rule of law as an “existing constitutional principle”. This is likely to eventually provide cover for higher court judges to block a centre-Right agenda, including by striking down Acts of Parliament, because it offends an ahistorical Blairite conception of the rule of law most clearly expressed by Lord Bingham.

The Telegraph: continue reading

Featured image: x.com

Leave a Reply