Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism

How carbon-backed CBDCs will come to be

ESCAPE KEY

When the European Union’s Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM) levies begin on 1 January 2026, most people will see it as just another tariff — a border charge on imports based on their carbon footprint.

What they won’t see is that CBAM is the first layer of a complete control architecture that, when fully deployed, will condition every transaction on carbon compliance — and eventually, any other parameter governments choose to encode.

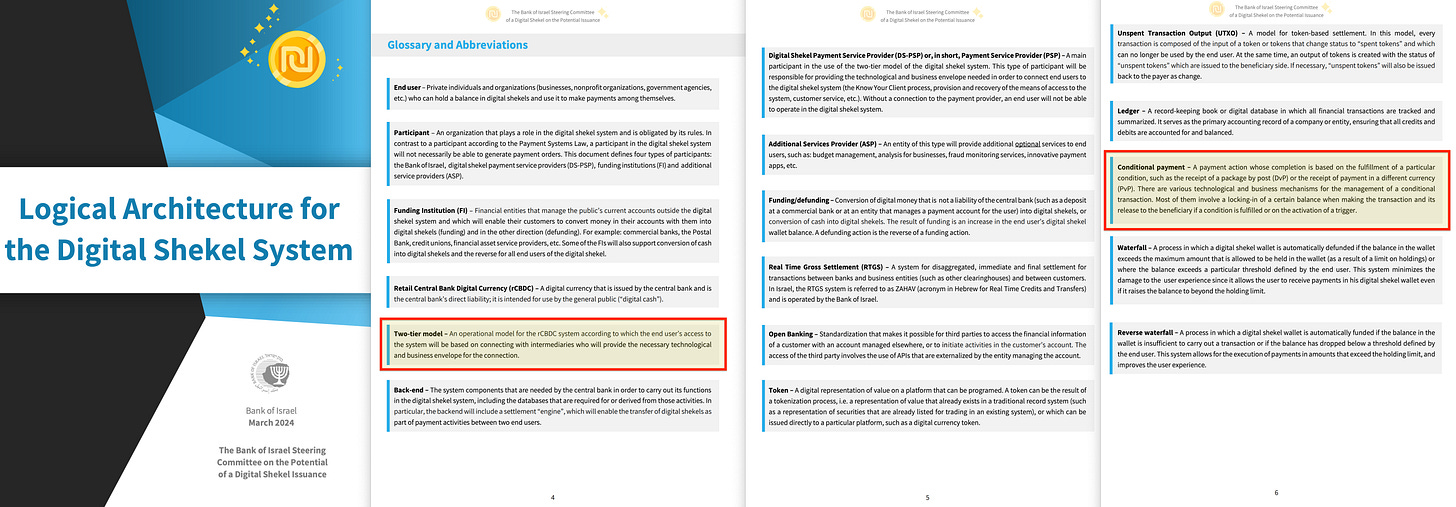

Whether you call it the ‘permission-based economy’, ‘compliance-based finance’, use the term adopted by the IMF1 or the Bank of Israel2 — conditionalPayment, or the term adopted on this substack — ‘conditional economics’, it’s all the same.

It just describes the mechanism from slightly different perspectives. Transactions which only take place, should you clear a given condition, be it related to ‘social justice’, ‘intergenerational justice’ or… ‘environmental justice’.

Conditional Economics: Read full story

A Constitutional Void: Read full story

The infrastructure is being built in public, documented in policy papers and technical specifications from the OECD3, the Bank for International Settlements, and the European Central Bank. What follows is how these seemingly separate initiatives — carbon border adjustments, digital product passports, central bank digital currencies, and programmable payment systems — connect to form a closed-loop system for governing economic behavior at the transaction level.

Spaceship Earth, if you will.

The Operationalisation of Spaceship Earth: Read full story

The Theory Behind the Machine

Three disciplines from mid-20th century systems science provide the blueprint: General Systems Theory, Input-Output analysis, and Cybernetics.

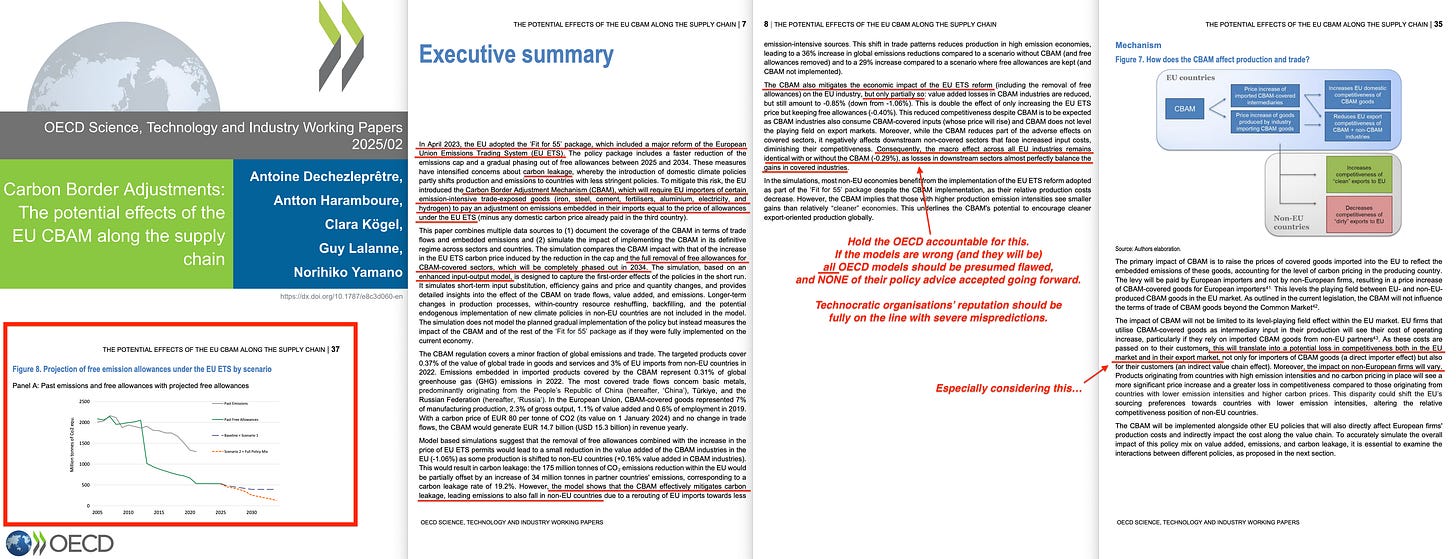

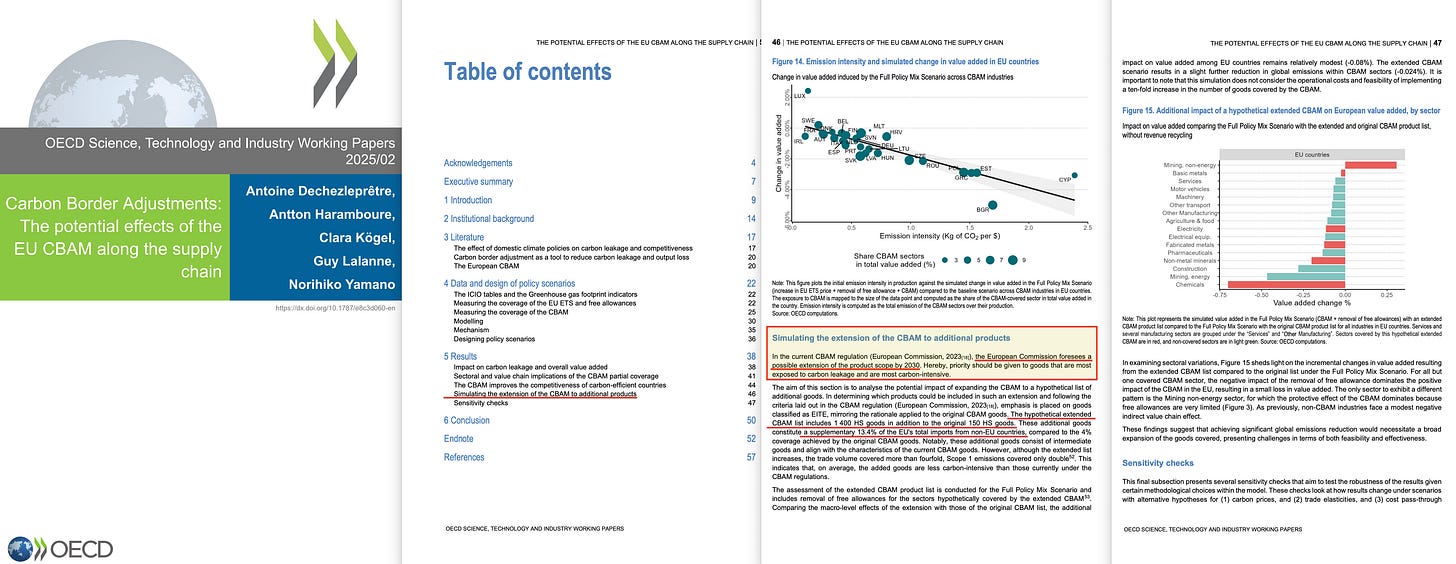

- General Systems Theory defines what’s being managed. The OECD’s recent working paper on CBAM draws the boundary explicitly: EU production covered by the Emissions Trading System4 plus all imports in covered sectors (currently cement, steel, aluminum, fertilisers, electricity, and hydrogen), along with their upstream supply chains. The system is mapped as a network — countries and sectors are nodes, trade and production relationships are links. Once you’ve drawn that boundary, you can model what happens when you introduce, say, a carbon price shock.

- Input-Output analysis provides the propagation math. Using OECD Inter-Country Input-Output5 (ICIO) tables mapping trade flows across 76 countries and 45 sectors, combined with greenhouse gas footprint data, the paper runs a Leontief price model6. This calculates direct effects (how a carbon price changes steel production costs) and indirect effects rippling downstream (how that steel price increase affects cars, construction, machinery — everything using steel as an input). Figure 7 shows sectoral impacts; Figure 11 visualises indirect value-chain effects — how a border adjustment propagates through users of covered inputs.

Once this propagation math works, you can hypothetically calculate the embedded carbon intensity of any product — not just raw materials at the border, but every finished good downstream. That number — kilograms of CO₂ equivalent per item — becomes calculable, standardised, and enforceable.

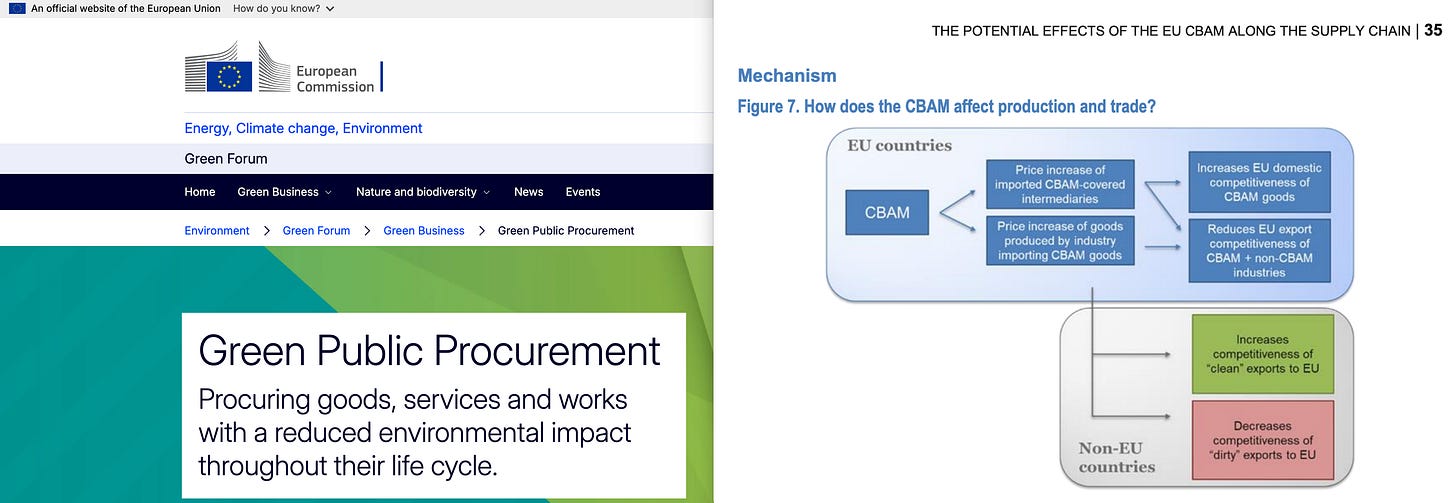

- Cybernetics closes the loop. Think of a thermostat: sensor (thermometer), comparator (checking against target), actuator (heater on/off), feedback (new temperature reading). The OECD paper’s ‘Mechanism’ diagram shows CBAM operating identically: sensors detect embedded emissions in imports, the comparator checks them against EU carbon prices, the actuator (CBAM levy) makes high-carbon imports more expensive, trade patterns shift, and new data feeds back to adjust parameters.

This is adaptive management — a system that observes outcomes and automatically adjusts to hit targets. Figure 8 shows this explicitly: the free-allowance phase-out schedule through 2034, gradually tightening the system like a ratchet. Set a target (55% emissions reduction by 2030), let the system adjust prices and gates to steer behavior toward that target, measure results, update parameters, repeat.

All roads lead to Basel: Read full story

Six Rails to Lock It Down

Theory requires infrastructure. What’s being built consists of six integrated layers — the ‘six rails’ — organised in three groups that map directly to the theoretical foundations: General Systems Theory defines the system, Input-Output analysis observes it, and Cybernetics controls it.

Beyond the Law – Summary: Read full story

Layer 1: Defining the System (General Systems Theory)

- Rail 0 (Pre-Rail): Standards — what we measure. ISO 140677 and Lifecycle Assessment8 methodologies define how to calculate product carbon footprints. CBAM’s method differs in specifics, but ISO/LCA standards9 are the likely domestic bridge via product passports. Without agreed measurement standards, you cannot define system boundaries or compare performance — you need a common unit of account.

- Rail 1: Digital Identity — who’s who, what’s what. Control systems need to know exactly which entity produced which product at which facility. EU Digital Product Passports10, mandatory for batteries from 18 February 2027 and expanding to other categories, create this: every item gets a credential — a QR code, NFC tag, or blockchain anchor — linking it to its carbon data, producer, and compliance status. These use the W3C Verifiable Credential standard11, making them machine-readable and cryptographically verifiable. Digital ID12 parameterises the nodes in the network.

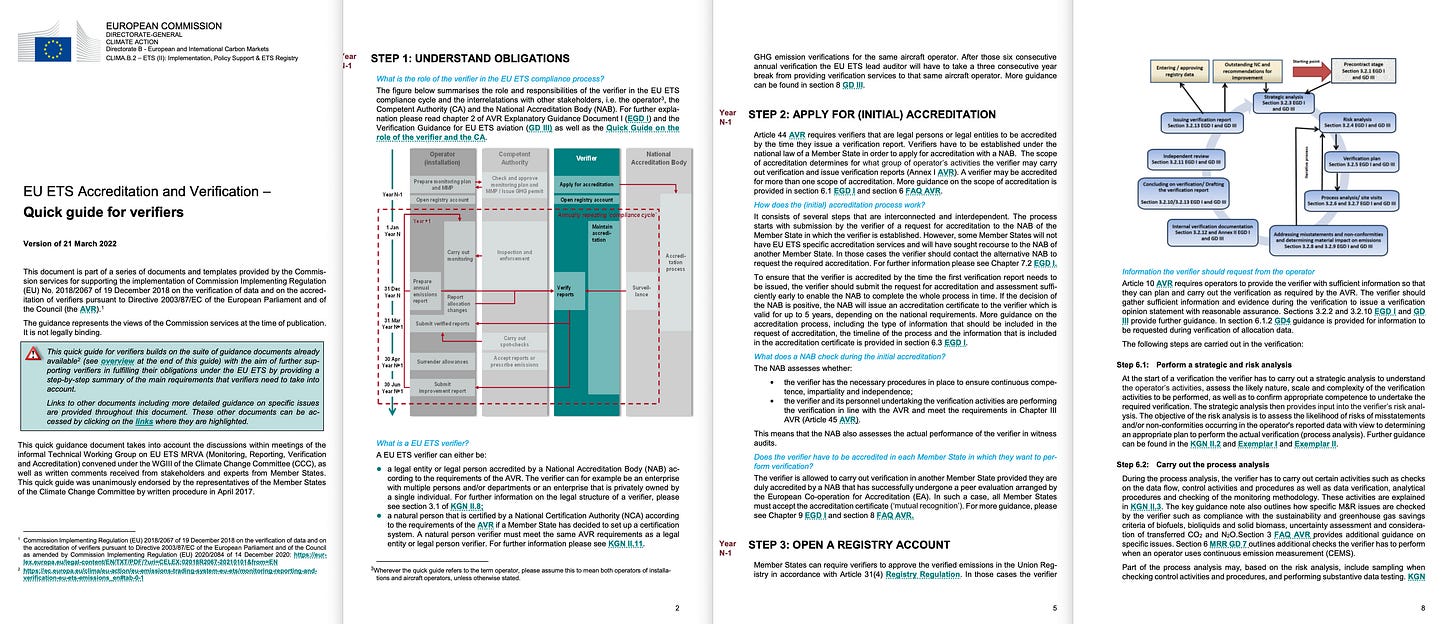

- Rail 2: Accreditation — who’s authorised. CBAM requires accredited verifiers to certify emissions declarations13. This creates a trust graph — authorised certifiers, approved methodologies, recognised data sources. Only accredited entities can make claims the system accepts as valid. Accreditation defines the boundary of legitimate system participants

These three rails define the system boundary and its components — exactly what General Systems Theory requires.

The Skeleton of Science: Read full story

Layer 2: Observing Propagation (Input-Output Analysis)

- Rail 3: Data — the sensors. OECD ICIO tables updated annually, facility-level monitoring and reporting (MRV systems)14, product passport data streams — this is the telemetry layer feeding the system’s sensors. As product passports roll out, this becomes continuous and granular: not just ‘steel has X intensity’ but ‘this batch from this facility has Y kgCO₂e’ (e=equivalent). Data captures the flows through the network that I-O analysis models.

- Rail 4: Audit & Assurance — the comparator. CBAM lets importers provide actual measured emissions data or fall back on OECD-calculated default values (sector/country averages)15. Declared values that beat defaults save money — but implausibly low declarations trigger audits. This variance mechanism compares claimed performance against expected performance (the OECD’s Leontief model baseline), flagging outliers for investigation. Defaults create a cost floor unless you verify lower. Audit checks observed flows against modeled propagation.

These two rails observe and validate system flows — exactly what Input-Output analysis requires to track how changes propagate through the network.

Input-Output Analysis: Read full story

Layer 3: Enforcing Control (Cybernetics)

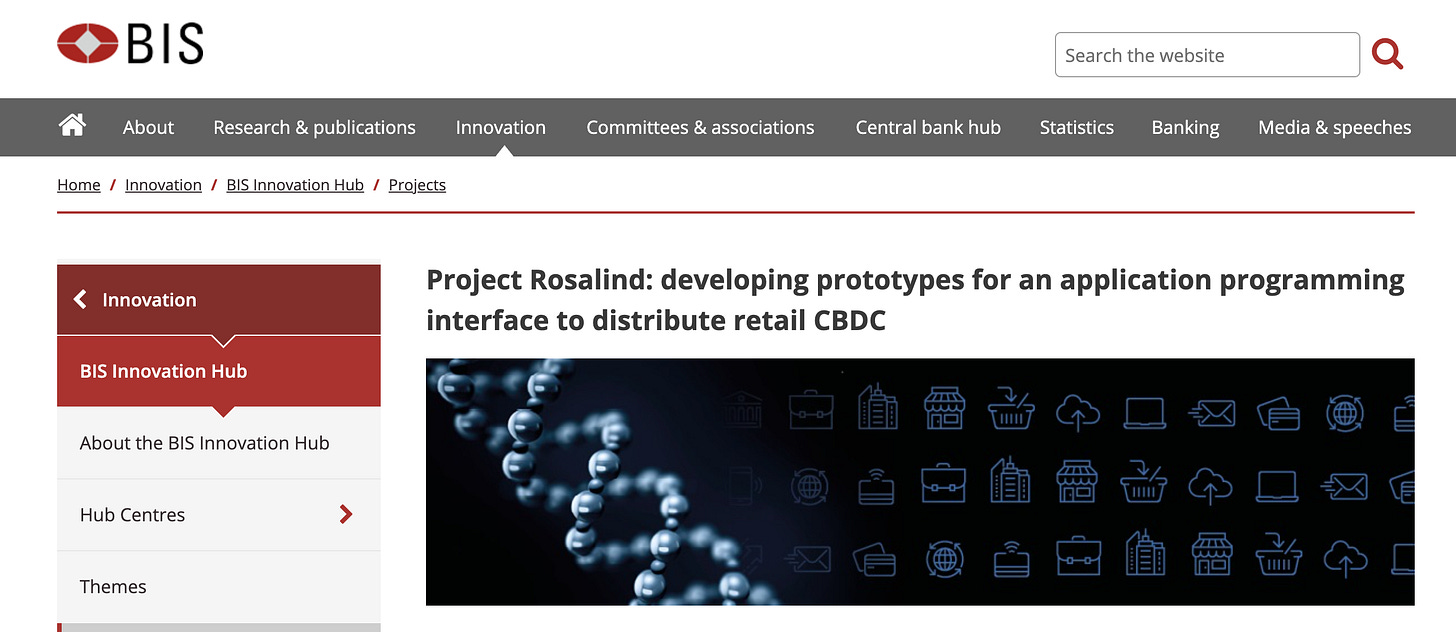

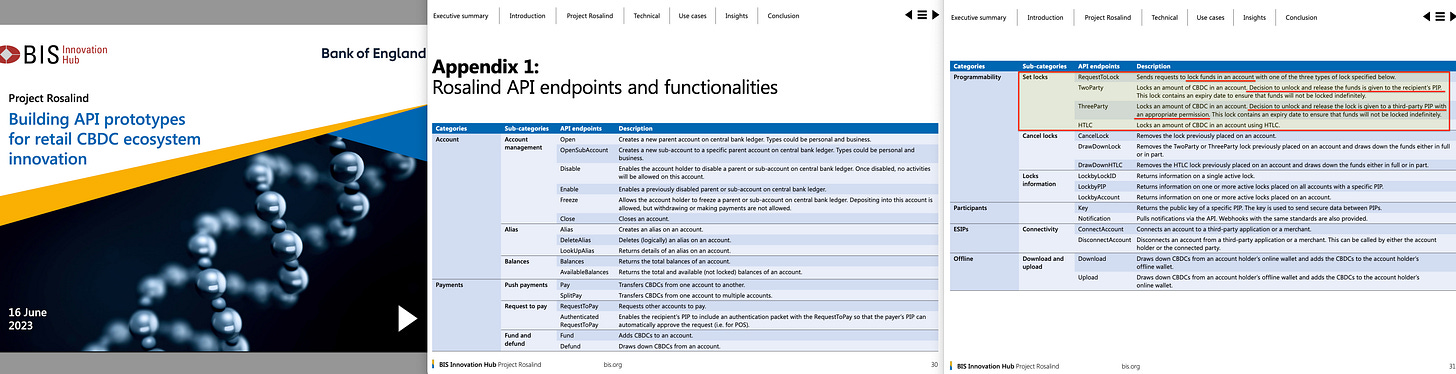

- Rail 5: Finance — the actuator. CBAM quantifies this precisely: the executive summary projects approximately €14.7 billion per year at €80/tCO₂e if trade flows don’t change. But finance extends beyond simple charges. Project Rosalind16, a joint initiative of the Bank for International Settlements and Bank of England, has developed a functional API for programmable payments which allow third parties to release payments based on conditions. The Bank of Israel’s Digital Shekel documentation describes the same capability through conditionalPayment functionality.

- Rail 6: Procurement — the mandate cascade. Once metrics exist, governments and corporations can require them. EU green procurement17 rules favor low-carbon bids. Corporate sustainability mandates require supplier carbon reporting. Retailers can make carbon credentials a condition of shelf access. This cascades through supply chains: to sell to a major buyer, you need the credential. Your suppliers need it to sell to you. Figure 7’s propagation effects show exactly how this flows down every tier. Procurement doesn’t just observe the network — it shapes behavior by making compliance a condition of participation.

These two rails apply corrective force to steer system behavior — exactly what Cybernetics requires for closed-loop control.

Cybernetic Thomism 2.0: Read full story

The Stack as Adaptive Management

┌─────────────────────────────────────────────────────┐

│ ADAPTIVE MANAGEMENT (closed-loop governor) │

├─────────────────────────────────────────────────────┤

│ CYBERNETICS: Control │

│ • Procurement (mandate: cascade requirements) │

│ • Finance (actuator: prices, locks, incentives) │

├─────────────────────────────────────────────────────┤

│ INPUT-OUTPUT: Observe & Calculate │

│ • Audit (comparator: variance detection) │

│ • Data (sensors: telemetry streams) │

├─────────────────────────────────────────────────────┤

│ GENERAL SYSTEMS THEORY: Define │

│ • Accreditation (boundary: who’s authorised) │

│ • Digital ID (nodes: who/what in the system) │

│ • Standards (metric: common unit of account) │

└─────────────────────────────────────────────────────┘Each theoretical layer requires specific infrastructure. GST needs standards, identity, and accreditation to define what’s being managed. I-O needs data and audit to observe flows and propagation. Cybernetics needs finance and procurement to enforce control. Together, they form adaptive management: define the system, measure its state, apply corrective force, observe results, adjust parameters, repeat.

The OECD paper operationalises GST (system boundary definition), I-O analysis (Leontief propagation math), and Cybernetics (the Mechanism diagram’s sensor-comparator-actuator-feedback loop). The six rails are the implementation layers that make the theory executable at scale.

Recursive Governance: Read full story

How Payment Locks Enable Conditionality

Project Rosalind’s architecture18 creates the foundation without explicitly naming the application. The BIS documentation describes a payment ‘lock’ mechanism — funds are locked in the payer’s wallet, a code is generated, and the transaction completes only when specific conditions are met. What the BIS calls infrastructure, central banks implement as policy.

In a standard digital payment, this operates as a Two-Party Lock: Person A buys from Person B, locking funds and sending a release code to B’s wallet. The architectural shift is the Three-Party Lock. Person A initiates payment, but a third party — a carbon registry, regulatory authority, accredited scheme — receives the lock code and evaluates programmed conditions: Does the buyer have sufficient carbon budget? Does the product meet compliance thresholds? The third party returns approve or deny. If approved, funds release. If denied, the lock expires and money returns to the buyer.

This provides plausible deniability for the BIS. They’re not implementing conditional payments — just a lock mechanism and API endpoints. The Bank of Israel’s Digital Shekel documentation makes this explicit with its ‘conditionalPayment‘ function. The technical elegance is that the same lock mechanism works identically regardless of what’s being checked — carbon budget, water quota, approved merchant category, sanctions screening. The API receives: wallet ID, amount, third-party endpoint. It returns: approve/deny.

Once Three-Party Lock is operational, adding a new condition is just registering a new verification endpoint. No software update to wallets, no change to core protocol — just a policy decision about what gets checked.

Project Rosalind: Read full story

From Border to Checkout

CBAM currently operates at the border — importers file declarations, pay levies, goods enter the EU. But the OECD paper explicitly models ‘extension to additional products’19 — expanding coverage to semi-finished goods, manufactured items, eventually consumer products. Once that happens, every retail item has a carbon score attached as a verifiable credential.

Combine that with the BIS/BoE Rosalind programmable payment infrastructure. At checkout, two modes become possible:

- Mode One — Second Price (the add-on): Your point-of-sale system scans barcodes and retrieves carbon credentials from product passports. It calculates the basket’s embedded emissions — say, 200 kgCO₂e. A scheme applies a per-kilogram fee based on ETS price or policy rate. ThreePartyLock routes that fee to a carbon offset fund or Treasury; the merchant receives the net. This is sugar tax logic, but automated, applied to every product, and machine-readable.

- Mode Two — Budget Gate (the allowance): Your digital wallet checks the basket’s carbon total against a threshold — a monthly budget, a benefit program condition, a municipal climate scheme. If you’re over your allowance, the system either blocks the transaction (CancelLock) or prompts you to purchase offset credits to proceed. If you’re under budget, DrawDownLock releases payment normally.

The actuator has moved from the customs house to the cash register. The comparator runs on every transaction. And the system doesn’t care whether you’re gating on carbon or something else — water use, land impact, biodiversity loss, nitrogen/phosphorus loading, labor practices, … even political compliance. The Stockholm Resilience Centre’s ‘Planetary Boundaries’20 framework identifies nine Earth system processes with quantifiable limits; carbon (climate change) is just one. Once the infrastructure exists, loading additional planetary boundaries into the comparator is just a parameter update. The rails work identically whether you’re enforcing carbon budgets, water quotas, or land-use compliance.

Planetary Boundaries: Read full story

12 Simple Steps to Rule the World: Read full story

What ‘Circular Economy’ Really Means

The term ‘circular economy’21 evokes recycling and sustainability. But in systems terms, it describes a closed-loop feedback system with the economy as the plant being controlled — Spaceship Earth.

The loop: Sensors (product passports, MRV systems, ICIO data) detect current state. Comparator checks against targets (carbon budgets per Figure 8’s phase-out schedule, procurement specs, emissions thresholds). Actuators (CBAM levies at the border per the executive summary’s €14.7bn projection, payment locks at retail, preferential finance terms) apply corrective pressure. Behavior shifts (buyers choose lower-carbon products, sellers invest in efficiency, trade patterns change per Figure 11’s indirect effects). New data flows back to sensors. Policymakers observe whether targets are met and adjust parameters — expand coverage, tighten thresholds, update allowances. The cycle repeats.

This is adaptive management operationalised. The OECD paper provides the quantitative justification (how much revenue, how much emissions reduction) and the technical method (Leontief propagation math, default factors, verification protocols). That makes it a reference implementation — not just theory, but a worked example that other jurisdictions can replicate.

The Circular Economy: Read full story

The Timeline and the Window

None of this is distant future:

- 1 January 2026: CBAM financial obligations begin22 (actual levies, not just reporting)

- 18 February 2027: Battery product passports mandatory23

- 2025-2026: Digital euro legislation expected24

- Through 2034: ETS free allowance phase-out runs on published schedule25 (Figure 8)

The EU moves first because it has regulatory capacity and political consensus. The UK follows by necessity26 — roughly half of UK trade is with the EU, and businesses selling into Europe need CBAM compliance anyway. The Bank of England developed Project Rosalind, so payment infrastructure is ready. A UK Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism has been announced; while details may differ, structure won’t diverge — compliance costs would be prohibitive otherwise.

Once the EU and UK deploy compatible systems, network effects lock them in. Exporters adopt the standards to access those markets. Other jurisdictions face a choice: align with the EU/UK model and maintain trade access, or face carbon tariffs and supply chain exclusion. Canada, Japan, South Korea, Switzerland, and Norway are likely next. The United States is conditional on political leadership, but the Inflation Reduction Act already created green subsidy infrastructure27, and if the EU and UK move, competitive pressure mounts.

By 2028-2030, this could be normalised across major economies: product passports mandatory, CBDCs operational with programmable features, carbon considerations at checkout routine first in benefit programs and loyalty schemes, then expanding scope. The window for stopping it is during the build-out phase — the next three to four years — not after deployment when businesses have invested billions in compliance and supply chains have restructured around the rules.

From Rosalind to Mandala: Read full story

What This Enables

Strip away policy language and look at the functional capability:

- Universal legibility: Every product carries a score. Every actor has verified identity.

- Conditional transactions: Payment release depends on comparator rules — carbon budget, credential status, procurement compliance, anything encodable.

- Granular control: Not sector-level or company-level, but per-item, per-transaction enforcement.

- Automated execution: No human discretion. The API evaluates rules and returns: approve or deny.

- Expandable scope: The same infrastructure that gates high-carbon products can gate anything with a measurable attribute.

The biblical ‘mark of the beast’ passage describes a system where no one can buy or sell without a mark. Whether you see this as prophetic or literary, the pattern is clear: commerce becomes conditional on system legibility and approval. What’s being built is infrastructure that enables exactly that — selective permission to transact, enforced automatically, at scale, with scope determined by whoever controls the comparator’s rule set.

You don’t need a ‘personal carbon ration law’ when payment finality itself is conditional. You don’t need enforcement agents when the payment system simply declines transactions that fail the rules. You don’t need new legislation to expand scope when the infrastructure exists and you’re just updating parameters.

Mark of the Beast: Read full story

The Choice Ahead

The documents are public. The OECD working paper, Project Rosalind’s API specifications for payment locks, the EU regulations mandating product passports, central bank consultations on programmable CBDCs. It’s openly published policy and technical documentation.

What most people miss is how the pieces connect. They see a carbon tariff, a supply chain transparency initiative, a digital payments upgrade. They don’t see sensor-comparator-actuator-feedback configured as a closed-loop governor scaling from borders to checkouts. When product passports carrying carbon credentials meet programmable CBDCs with ThreePartyLock functionality, you get carbon-backed currency — money whose usability is conditional on carbon compliance. The carbon intensity attached to goods (via product passports) becomes a constraint on the medium of exchange itself (via payment locks). That’s not a carbon tax. That’s carbon as the basis for transactional permission.

The infrastructure is being built right now. The timeline is clear: levies from 1 January 2026, battery passports from 18 February 2027, digital currency rollout through the late 2020s, ETS ratcheting through 2034. The window for democratic resistance, legal challenges, or alternative trade arrangements is narrow and closing. Once systems are operational at scale and economically embedded, reversal becomes politically impossible.

Whether you call this ‘technocratic overreach’, ‘necessary climate governance’, ‘inclusive capitalism‘, ‘carbon communism’, … or Spaceship Earth depends on your values. But what it enables cannot seriously be called into question. The regulations are in force, and the pilots are running.

We have perhaps until 2028-2029 before this transitions from build-out to fully operational deployment. What happens in that window will determine whether this becomes the new normal or whether enough people see what’s being built and decide the cost of that kind of control — however well-intentioned — is too high.

Inclusive Capitalism: Read full story

Quick-Start Guide for the Navigator of Spaceship Earth: Read full story

Closing the Loop: From Labor Time to Carbon Time

The system architecture is furthermore compatible with Marx’s concept of ‘socially necessary labor time’28 — the average labor required to produce a commodity, which Marx proposed as the true measure of value. Except here, what’s tracked is not human labor input, but carbon dioxide equivalent.

The bridge between them runs through Marx’s Fragment on Machines29, which described the historical transfer of human work into machinery — labor crystallised in capital equipment. Once production shifts from human effort to machine processes, energy consumption becomes the measurable proxy for embedded labor. And energy consumption, in a fossil-fuel economy, translates directly to carbon emissions. The carbon intensity of a product thus becomes a modern encoding of the socially necessary labor — now mechanised — required to produce it.

This creates a neat inversion of Technocracy Inc.’s 1930s proposal for ‘energy certificates’ — currency backed by energy consumed in production, measured in joules rather than dollars. What Howard Scott and the technocrats envisioned as energy IN (productive capacity you’ve earned through energy consumption) becomes carbon OUT (environmental debt you’ve incurred through emissions). Both are measuring the same thermodynamic process from opposite ends. Technocracy Inc. lacked the measurement infrastructure to implement their vision. Carbon accounting now has it: continuous monitoring, automated calculation, cryptographic verification, transaction-level enforcement.

What the Victorians tracked in labor hours, what the Soviets attempted to plan through labor vouchers, and what the technocrats proposed to measure in energy units, can now be monitored in kilograms of CO₂e — measured automatically, verified cryptographically, and enforced at the point of transaction.

The infrastructure that eluded twentieth-century planned economies is being built by twenty-first-century carbon accounting. Same cybernetic logic, different units of measure, … vastly superior technical capability.

The Red Star: Read full story

Technocracy, Inc.: Read full story

The Carbon Currency: Read full story

Anticipated Objections and Rebuttals

- ‘This is conspiracy thinking. You’re connecting unrelated policies to suggest coordinated control’.The coordination is documented, not inferred. The OECD working paper on CBAM (ECO/WKP(2023)31) explicitly models ‘extension to additional products’ and calculates downstream propagation effects using Inter-Country Input-Output tables. Project Rosalind’s final report details API specifications for conditional payments. The EU’s Digital Product Passport regulation (EU 2023/1542) requires W3C Verifiable Credentials — the same standard CBAM verification uses. The Bank of Israel’s Digital Shekel Challenge documentation describes

conditionalPaymentfunctionality. These aren’t separate initiatives that happen to align — they reference each other in technical specifications and use interoperable standards by design. When the BIS and central banks publish APIs for ‘ThreePartyLock’ allowing external entities to condition payment release, that’s not theoretical — it’s implemented code with documented endpoints. - ‘Carbon border adjustments are just tariffs. We’ve had import duties forever without becoming a surveillance state’.Traditional tariffs operate on product categories at borders. CBAM requires facility-level emissions data, verified by accredited bodies, for every production input upstream. Article 4 of the CBAM regulation mandates ‘actual embedded emissions’ based on specific production processes, not generic product categories. That necessitates supply chain transparency to the source facility level. When combined with Digital Product Passports carrying this data as machine-readable credentials, you’ve created per-item traceability and scoring. Traditional tariffs don’t require your toaster to carry a QR code linking to its production facility’s energy consumption data. CBAM does — and once that infrastructure exists, the data is available for other uses. The qualitative difference is granularity: from category-level (HS codes) to item-level (unique identifiers).

- ‘Scope expansion requires new legislation. Democracies won’t just authorise transaction-level control’.First, the EU operates through regulatory expansion under framework directives. The ETS Directive allows the Commission to add sectors and adjust parameters without new primary legislation — Figure 8’s phase-out schedule through 2034 runs automatically. Second, scope expansion often happens through procurement mandates and industry standards rather than direct regulation. When the EU requires green public procurement, and corporations adopt ESG supplier requirements, carbon credentials cascade through supply chains without new consumer-facing laws. Third, crisis framing creates political permission for extraordinary measures. The EU Green Deal passed during COVID, when normal legislative resistance was muted. Climate emergency declarations in 2,000+ jurisdictions create legal basis for executive action. The pattern isn’t ‘propose transaction control and vote on it’ — it’s ‘expand existing frameworks incrementally under crisis justification’.

- ‘This infrastructure is too complex and expensive to deploy at scale. It’ll collapse under its own weight’.The ETS has operated for 18 years covering 10,000+ installations across 30 countries, processing millions of allowance transactions annually. CBAM’s reporting phase (2023-2025) successfully collected data from thousands of importers across six sectors. The technical complexity argument fails because:

- Standards already exist and are proven (ISO 14067, GHG Protocol, ICIO tables updated since 2005)

- Automation reduces marginal costs dramatically — once the first battery passport system is built, adding the millionth credential costs nearly nothing

- Large corporations bear initial costs and then pass them to suppliers, creating a compliance cascade where each tier bears its own verification cost

- Digital systems scale in ways physical inspections don’t — a border agent can check 100 shipments per day; an API can process 100,000 transactions per second

The question isn’t ‘can this scale?’ — it’s ‘who bears the cost?’ And the answer is: it’s distributed through supply chains as a cost of market access, making it individually small enough to be tolerable even as it totals enormous aggregate compliance expenditure.

- ‘People will resist. You can’t force carbon budgets on consumers’.You don’t need to force anything visible. The architecture works through graduated pressure:

- Phase 1 (now-2028): Business-facing only. Importers pay CBAM levies. Manufacturers need product passports. Consumers see none of this directly.

- Phase 2 (2028-2031): Pricing mechanisms. Carbon-intensive products cost more due to embedded compliance costs. Consumers experience this as normal price variation, not rationing.

- Phase 3 (2031+): Conditional incentives. Loyalty programs offer discounts for low-carbon purchases. Benefit programs (food assistance, housing subsidies) condition payments on approved purchases. Green mortgages offer better rates with smart meter monitoring. These are opt-in initially — you ‘choose’ to participate for the financial benefit.

- Phase 4 (mid-2030s): Default conditionality. If CBDCs become primary payment rails and cash is marginalised (already happening — Sweden 80%+ digital, China pushing e-CNY), then programmable conditions become the norm. You don’t ‘force’ anything — you architect choice contexts where compliant behavior is financially optimal and non-compliant behavior is expensive or unavailable.

The boiling frog is real. By the time visible restrictions appear, the alternative infrastructure (cash, non-credentialed supply chains) has atrophied.

- ‘Courts will strike this down as government overreach’.On what legal basis? Consider:

- Commerce Clause / Single Market: Governments can regulate interstate/intra-EU trade for public health, safety, and environmental protection. That’s established law (US Clean Air Act, EU ETS, tobacco regulations).

- Taxation Power: Carbon levies are taxes on imports. Border carbon adjustments are facially similar to VAT/sales tax systems that already condition transactions on compliance.

- Private Sector Execution: Much of this operates through private procurement requirements, corporate ESG policies, and voluntary standards (ISO certifications). Courts defer to private contract enforcement.

- No Recognised Right Being Violated: There’s no constitutional right to anonymous commerce, no right to high-carbon products, no fundamental liberty interest in avoiding environmental accounting. Legal challenges need a rights violation — ‘I don’t like surveillance’ isn’t a winning legal argument without showing how a specific protected right is infringed.

The EU’s General Data Protection Regulation faced privacy challenges and survived. Financial AML/KYC requirements face anonymity challenges and survive. Product safety requirements that exclude non-compliant goods survive. The legal theory for stopping this is weak, and by the time litigation resolves (5-10 years), the infrastructure is operational and economically embedded.

- ‘Other countries won’t adopt this. The EU will be isolated’.Network effects and competitive pressure make adoption likely:

- Export compliance: Any business selling to the EU needs CBAM compliance. That means investing in carbon accounting and verification infrastructure. Once that investment is made, maintaining separate non-compliant systems for other markets is expensive duplication. Businesses standardise on the most stringent requirement.

- Competitive neutrality: If the EU and UK represent 25-30% of global GDP and adopt carbon border adjustments, non-adopting countries face a choice: accept that their exporters pay carbon levies (money flowing to EU/UK treasuries), or implement domestic carbon pricing and rebate/offset systems so the revenue stays home. Most will choose the latter.

- First-mover infrastructure advantage: The EU is building the verification bodies, the standards, the accreditation systems. Other countries can either build parallel infrastructure (expensive) or recognise EU-accredited verifiers and adopt EU standards (cheap). Path of least resistance is convergence.

- Financial system integration: If the BIS facilitates Project Jura/Rosalind/mBridge integration among central banks, and programmable payment capabilities become standard CBDC features, then the technical capability exists globally even if policies differ by jurisdiction.

China won’t adopt EU rules directly, but might build compatible-but-competing infrastructure (already developing green finance taxonomy, planning national ETS expansion, piloting e-CNY with programmable features). The result is multiple systems with similar capabilities, not EU isolation.

- ‘You’re fearmongering. This is just climate policy, not social control’.Distinguish between intent and capability. Assume every architect of this system has pure intentions and genuinely believes they’re saving the planet. That doesn’t change what the infrastructure enables.Consider the structure:

- Universal product identification and scoring

- Verified digital identity for all economic actors

- Continuous monitoring and data collection

- Automated comparison against programmed thresholds

- Conditional transaction execution based on compliance status

- Ability to update parameters and expand scope without rebuilding infrastructure

That’s a general-purpose control system. The fact that it’s currently being used for carbon doesn’t limit what it could be used for. The Bank of Israel’s

conditionalPaymentfunction doesn’t check what condition you’re encoding — it just evaluates: true/false, approve/deny.Historical precedent is instructive:

- Income tax withholding was introduced as temporary wartime measure (1940s), became permanent infrastructure for tax collection, compliance monitoring, and data gathering far beyond original scope

- Social Security numbers were promised to never be used for identification (1936), became de facto national ID in the US

- Anti-terrorism finance surveillance after 9/11 (PATRIOT Act, FATF standards) created banking surveillance infrastructure now used for tax enforcement, sanctions, and regulatory compliance far beyond terrorism

- Public health emergency powers during COVID were used for lockdowns, business closures, and movement restrictions unprecedented in peacetime

The pattern: build infrastructure for one purpose, expand scope once operational. This isn’t conspiracy — it’s institutional logic. Bureaucracies use available tools, and once tools exist, the temptation to use them for additional ‘good purposes’ is overwhelming.

Calling this ‘fearmongering’ requires believing that:

- The infrastructure won’t be built (contradicted by published regulations and timelines)

- The infrastructure can’t be used for other purposes (contradicted by parameter-agnostic API design)

- Institutions won’t expand scope when politically convenient (contradicted by historical precedent)

- ‘There are legitimate technical alternatives that don’t require centralised control’.Propose them, implement them, and get them adopted now — before 2026. The EU didn’t choose centralised accreditation and programmable payments because alternatives don’t exist. They chose it because:

- Enforcement requires verification: Carbon accounting is gameable without third-party verification. Decentralised systems have no enforcement mechanism when actors lie. The EU tried ‘trust but verify’ approaches in early ETS — resulted in massive fraud (VAT carousel fraud cost €5B).

- Interoperability requires standards: If every jurisdiction uses different carbon accounting methods, trade becomes impossible. Standards require standard-setters. Who sets them in a ‘decentralised’ system?

- Compliance requires conditionality: If high-carbon products can still be sold without penalty, behavior doesn’t change. Conditionality requires enforcement at the transaction level, which requires payment systems to evaluate compliance status.

Privacy-preserving alternatives (zero-knowledge proofs, etc) are theoretically possible but practically immature and lack regulatory acceptance. By the time they’re ready, the centralised infrastructure will be operational. Building alternatives requires political will, technical capacity, and coordinated implementation across jurisdictions. Where is that effort? Who’s funding it? Which governments are deploying it?

Saying ‘alternatives exist’ without demonstrating adoption pipeline is wishful thinking.

- ‘Even if deployed, this will fail. Black markets, workarounds, and resistance will make it unworkable’.Partial compliance is sufficient for the system to work. Consider:

- Black markets exist for cigarettes (~20% of global cigarette trade), yet tobacco taxation still dramatically reduced smoking rates and raised revenue. The system doesn’t need 100% compliance — it needs to make non-compliance expensive and inconvenient enough that most actors comply most of the time.

- Cash use is declining voluntarily in many countries (Sweden 10% of transactions, South Korea 20%, UK 17%) without forced elimination. The system doesn’t need to ban cash — just make digital payments more convenient and gradually withdraw cash infrastructure (bank branches closing, ATMs removed, merchants refusing cash for ‘efficiency’).

- Supply chain verification already works for conflict minerals, organic certification, and halal/kosher food. Fraudulent certification exists, but the systems function well enough to create market differentiation and price premiums. Perfect isn’t required — good enough is sufficient.

- China’s social credit system operates with imperfect coverage (not every citizen, not every transaction) yet still shapes behavior through periodic enforcement and visible examples. The panopticon works through uncertainty — you don’t know when you’re being watched, so you comply preemptively.

The system is resilient to partial defection because:

- Large actors (major corporations, formal sector businesses) have too much to lose from non-compliance — they’re locked in through supply chain dependencies and market access requirements

- Small-scale evasion is economically insignificant and can be tolerated

- Enforcement can be selective — make examples of visible violators to encourage compliance among others

- Network effects mean that as compliance reaches 60-70%, the non-compliant are increasingly marginalised (can’t access mainstream supply chains, payment systems, or markets)

The question isn’t ‘will there be resistance?’ — there always is. The question is ‘will resistance prevent deployment or force rollback?’ History suggests no. GDPR faced resistance, got deployed anyway, and is now normalised. Tobacco regulations faced massive industry resistance, got deployed, and smoking rates dropped. Financial surveillance faced privacy objections, got deployed, and is now routine.

Resistance slows deployment and creates friction. It rarely stops systems with institutional momentum, technical capability, and elite consensus.

The Architecture Is The Trap: Read full story

The Complete Architecture: Read full story

The Road to Algorithmic Authoritarianism: Read full story

A Digital World Order: Read full story

https://thenewobjectivity.com/pdf/marx.pdf

This article (Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism) was created and published by Escape Key and is republished here under “Fair Use”

••••

The Liberty Beacon Project is now expanding at a near exponential rate, and for this we are grateful and excited! But we must also be practical. For 7 years we have not asked for any donations, and have built this project with our own funds as we grew. We are now experiencing ever increasing growing pains due to the large number of websites and projects we represent. So we have just installed donation buttons on our websites and ask that you consider this when you visit them. Nothing is too small. We thank you for all your support and your considerations … (TLB)

••••

Comment Policy: As a privately owned web site, we reserve the right to remove comments that contain spam, advertising, vulgarity, threats of violence, racism, or personal/abusive attacks on other users. This also applies to trolling, the use of more than one alias, or just intentional mischief. Enforcement of this policy is at the discretion of this websites administrators. Repeat offenders may be blocked or permanently banned without prior warning.

••••

Disclaimer: TLB websites contain copyrighted material the use of which has not always been specifically authorized by the copyright owner. We are making such material available to our readers under the provisions of “fair use” in an effort to advance a better understanding of political, health, economic and social issues. The material on this site is distributed without profit to those who have expressed a prior interest in receiving it for research and educational purposes. If you wish to use copyrighted material for purposes other than “fair use” you must request permission from the copyright owner.

••••

Disclaimer: The information and opinions shared are for informational purposes only including, but not limited to, text, graphics, images and other material are not intended as medical advice or instruction. Nothing mentioned is intended to be a substitute for professional medical advice, diagnosis or treatment.

Disclaimer: The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of The Liberty Beacon Project.

Leave a Reply