Trial by Jury

IAIN HUNTER

In the wake of the protests and riots which were a response to the murders in Southport last year of three little girls, our glorious Prime Minister promised swift ‘justice’ for the ‘far-right criminals and thugs’ who were involved. He ordered twenty-four-hour courts to operate to convict and imprison as many people as possible as rapidly as possible. Grand-standing judges swiftly sentenced people brought before them who had been advised to plead guilty in exchange for some leniency. Or so they thought. Tell that to Lucy Conolly or to the spirit of the late Peter Lynch who committed suicide in jail.

I wrote in Part Three that they should have been advised to claim their rights under Magna Carta:

No free man is to be arrested, or imprisoned, or disseised, or outlawed, or exiled, or in any other way ruined, nor will we go against him or send against him, except by the lawful judgment of his peers or by the law of the land.

Lawful judgement of his peers means a Trial by Jury; Law of the Land is Legem Terrae, which includes Common Law, our ancient laws and customs as well as judge-made case law, stare decicis, which is what the legal profession regards as common law.

Of course, they would not have had a Trial by Jury as was understood by our ancestors, one in which a unanimous verdict is needed to convict, one in which the judge does not direct the jury, one in which the most important function of the jury is to examine the law or statute that has been used to bring the accused to court. Nor would they have been judged by the jury whose only function in a modern Jury Trial is to weigh the evidence presented and determine the guilt or innocence of the accused from that alone.

Neither would the jury have been peers of the accused as they would have been in 1215. That would mean that the jury should be composed of men, or women, of the same social and economic standing as the accused who would have a deep understanding of the life and troubles of the person brought before them. That would be almost impossible today with class, educational attainment, race, religion and diverse political outlooks among the jurors all muddying the waters.

It is no secret that the present government wants to do away with Jury Trials. More than 90% of cases that come to court are tried without a jury. That includes nearly all civil law cases since the Administration of Justice (Miscellaneous Provisions) Act of 1933. The recent ‘climate trial’, Mann v Steyn, held before a jury in Washington DC would almost certainly not have happened before a jury in Britain. Other examples of trials without juries are the Diplock Courts in Northern Ireland and the notorious family courts in which judges even have the power to jail anyone present if they talk about the case outside the court at any time. If you wish to know more about these, go to UK Column.

It is noteworthy that on several websites such as this one you will find statements that the history of Trial by Jury can be traced back to English Common Law and a significant milestone of the development of Trial by Jury was Magna Carta. This is not true. It was certainly a feature of justice in pre-conquest England, but it stretches right back through history to Athens in the late sixth century BC.

The Athenian Cleisthenes acknowledged the need to spread empowerment through society to promote justice, liberty, peace and prosperity. Devolved power had to go all the way down to the poorest male citizens, the thetes, by recognising rights, exousia.

Exousia included the right of an accused to a Trial by Jury and the empowerment of citizens by bestowing upon them judicial authority as Jurors. The jurors would examine laws and measures passed by legislatorial majorities in assembly and could judge, overrule or annul them whenever this was thought necessary to serve justice, liberty and the interests of the people. Trial by Jury, then, was at the very core of democracy itself.

This concept was understood by the Romans, and developed through the Anglo-Saxon Heptarchy, in particular Wessex which was ruled by the Domboc of Alfred. King Alfred upheld the established right of jurors to find verdicts according to their judgement which endured into pre-Norman England in which something akin to Trial by Jury existed in the folc-gemot and shire-gemot.

Lest we think Saxon England was special, on the continent of Europe, Holy Roman Emperor Conrad II installed Trial by Jury a full two centuries before Magna Carta. The duty of jurors to decide verdicts according to their convictions and annul unjust prosecutions had long been established and remained firmly so.

Before continuing, we need to understand exactly what Magna Carta was. It was nothing less than a peace treaty between the Barons and King John in which the church under Archbishop Stephen Langton assisted and burghers and freemen were present. It did not form the basis for, or otherwise create, the right to a Trial by Jury, rather it was a restatement of judicial customs of long standing. It was a Common Law contract between the Crown and the People, made in perpetuity, which set the principle that no-one, or nothing, is above the law. Not even a King. Certainly not a Prime Minister and a Parliament. Altering it is unconstitutional.

Hence Magna Carta did not grant anything as such, it was an agreement that old laws and customs would endure. The danger in thinking that anything is granted by an ancient parchment or any more modern document brings with it the idea that rights are in the gift of a state authority or some supra-national body which produced the document. This simply cannot be. Inalienable rights come from a higher power than the state and we assume the existence of such a higher power – God – or else some elements of humanity will assume the power for themselves and subjugate the rest. That is exactly what we have seen unfold before us in our times.

In 1688, Parliament rejected one anointed king and chose another in an episode known as the Glorious Revolution. With the succeeding Act of Wil. & Mar. and the Bill of Rights it claimed sovereignty for Parliament. This in turn led to the emergence and rise of the political parties until today we have a governing body that writes legislation, decides on the punishments for infringements, and employs agents (judiciary and police) to enforce its legislation. That is tyranny. Being permitted to vote for representatives of one party or another every few years to determine which party forms the executive arm of government does not constitute democracy.

People do not understand what true democracy is. It is certainly not mere voting. Nor is it the result of one election giving one political party a parliamentary majority which then allows them to do whatever they want until either another election must be called, or the government falls. That, unfortunately, is what much of the British public thinks democracy is because that is what they have been taught. It is the triumph of miseducation by omission and the state-driven judicial subversion of due process.

Trial by Jury is the power of the people to govern themselves. In a Common Law Trial by Jury, the twelve jurors, who will be peers of the defendant as described, will act as judges. There is presiding officer or convenor who oversees proceedings. The jurors have independence in their decision making and they will swear an oath, hear evidence and place themselves in the shoes of the defendant to establish whether or not mens rea has been proved and an actus reus has been committed – whether the defendant is guilty or innocent.

The jury must also judge the law. They must establish that the law or legislation the defendant is accused of breaching is not against common right and reason or repugnant, or impossible to comply with. For example, a defendant may be guilty of an act which infringes a law or legislation, but the jurors may judge that the law or legislation is unjust, unfair or infringes upon the inalienable rights of the defendant. They then have the obligation to render void that law or legislation. This is known as annulment by jury or jury nullification.

Sir Edward Coke, barrister, judge and politician in 1610: The Common Law doth control Acts of Parliament and sometimes shall adjudge them to be void. For when an Act of Parliament is against Common right or reason, or repugnant, or impossible to be performed, the Common Law will control it and adjudge such Act to be void.

As the law professions have grown and extended their tentacles into nearly all aspects of public life, lawyers have moved into politics in numbers to write legislation through which they might subsequently profit by handling cases. A self-important judiciary has, over the centuries, steadily usurped the rights and duties of jurors. The first loyalty of lawyers is to their own profession, not necessarily justice.

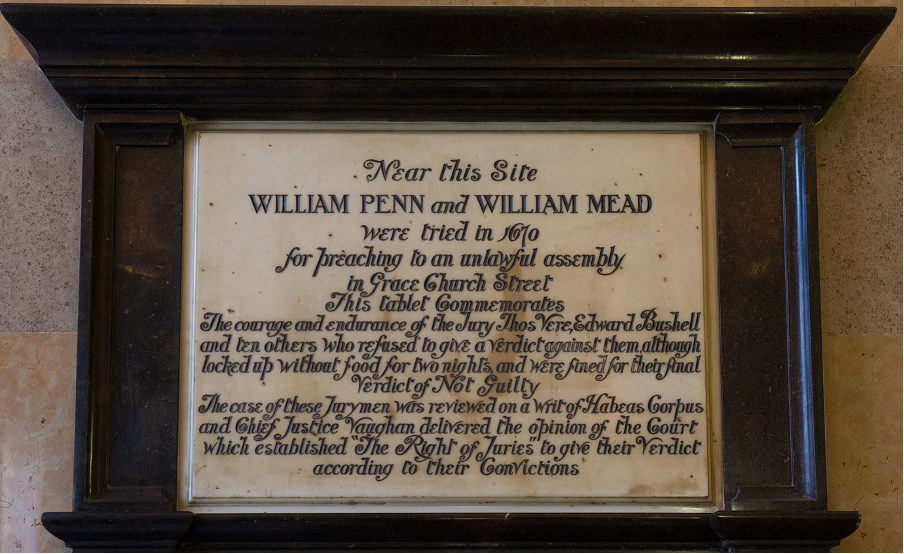

However, in the Central Criminal Court of England and Wales, the Old Bailey, there is a constant reminder of the truth in the plaque below. It commemorates the trial of William Penn and William Mead for ‘preaching to an unlawful assembly’. The wording states that the right of juries to give their verdicts according to their convictions was established by Chief Justice Vaughan but this is a distortion of the truth as the right had long been understood.

The Penn and Mead trial took place in 1670. Quakers Penn and Mead knowingly and intentionally broke the law, and the facts of the case were known to all, to the judge, jury and public. The defendants made no attempt to deny what they had done. On the contrary, to use modern parlance, they ‘doubled down’ during their trial. What they disputed was their ‘guilt’. They claimed they were not guilty because for an act of injustice to be a crime it requires malice aforethought (mens rea). The Recorder of London, Sir John Howel, denied Penn the right to see the charges laid against him and a list of laws he had broken. In addition, he directed the jury to reach a verdict without hearing the defence.

Despite pressure from Howel to convict Penn and Mead, the jury returned a verdict of “not guilty”. When told to reconsider and to select a new foreman, they refused and were imprisoned for several nights to mull over their decision. The Lord Mayor of London, Sir Samuel Starling, also on the bench, told the jury, “You shall go together and bring in another verdict, or you shall starve”, and not only had Penn sent to jail in Newgate Prison (on a charge of contempt of court for refusing to remove his hat), but the full jury followed him, and they were additionally fined the equivalent of a year’s wages each.

The members of the jury fought their case from prison in what became known as Bushel’s Case and Lord Chief Justice Sir John Vaughan acquitted them. In doing so he underscored the right for all English juries to be free from the control of judges. This case was one of the most important trials that shaped the concept of jury nullification and was a victory for the use of the writ of habeas corpus as a means of freeing those unlawfully detained.

William Penn was no ordinary man as a perusal of his Wikipedia entry will reveal. He became a loyal friend and adviser to King James II and went on to found Pennsylvania.

If you are intrigued by the idea of jury nullification and wish to know more, at commonlawcontituiton.org there is a link to a 17,000 word academic paper on the subject.

If you would like to read a transcript of the Trial of William Penn and William Mead you can read it here.

What I have been describing so far is the Petit Jury. Forgotten for over ninety years in Britain There is also the Grand Jury. Fortunately, there is a Grand Jury Museum based in Canterbury in Kent. Here we can read how the Grand Jury was abolished in the British Constitution by the Administration of Justice (Miscellaneous Provisions) Bill of 1933. The prime mover of the Bill was the Lord Chancellor Viscount Sankey who was appointed by Labour Prime Minister Ramsay Macdonald and whom we can see was a member of the Fabian Society.

So, what is, or was, a Grand Jury? a Grand Jury examines accusations made against persons who may be charged with a crime. It determines the facts and, if the evidence warrants, makes formal charges on which accused persons are later tried. It does not decide guilt or innocence. Its function is inquisitorial and accusatorial. It decides whether or not there is “probable cause” or “prima facie evidence” to believe that a person has committed a crime.

Should a Grand Jury so decide, an indictment – a formal accusation of crime – is returned and the accused must stand trial before a petit, or trial, jury whose duty is to determine the question of guilt “beyond a reasonable doubt.”

The grand jury enjoys greater independence than the petit jury. It is instructed by the court prosecutor on questions of law and fact, but its investigations are relatively free from supervision. Although the jury may work closely with the prosecutor, it is not formally under his control.

In theory, anyone may establish a Grand Jury, and it could be done at any level. Your Parish Council could establish one. It would decide whether or not there is a case to answer, and the details could be passed to the Department of Public Prosecutions, now the Crown Prosecution Service for action. Normally a Grand Jury would have 24 jurors and only 12 out of the 24 are required to indict someone. The defendant does not give evidence, that is laid before the Petit Jury at any subsequent trial.

Grand Juries still take place in the USA and the most recent one that readers may be aware of is the one organised by German lawyer Reiner Füllmich into the alleged criminal activities that took place during the so-called Covid pandemic. For that he still languishes in a German jail, a victim of politically motivated ‘lawfare’.

Could Common Law Trials by Jury be re-established in Britain? There would be open conflict with the Law professions and the judiciary. Almost certainly no-one currently practicing law will have been taught real Common Law since it was dropped from the syllabi of law schools in Britain around 1970. The legal profession regards stare decisis as common law, that is law made by the decisions of judges in individual cases which stands unless over-ruled by a higher court. That is not to say all such law is bad. Far from it. But who appoints judges? The Judicial Appointments Commission which is an arm of the Civil Service, hence the government. Who pays judges? The government. Therefore, is not stare decisis government-made law without a debate and vote in Parliament? Furthermore, Lawyers do not become judges without agreeing to the principles of DEI so any decisions they might make would also be passed through that Marxist prism.

There is a mountain to climb before it could be done because the truth and the history have been very craftily hidden from people for a very long time. It requires individuals to become interested, to re-educate themselves, to learn about Common Law and become sovereign men and women. They would have to learn how to be jurors. It is not something that is going to happen overnight but with determined organisation and leadership, coupled with a growing public awareness and a dedicated campaign, anything is possible, even if it has to take a generation or more.

This article (Common Law: A Way to Make Government Serve Us – Part Four) was created and published by Iain Hunter and is republished here under “Fair Use”

Leave a Reply