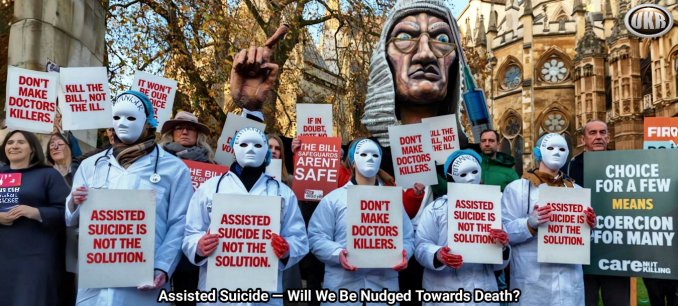

Assisted Suicide — Will we be nudged towards death?

LAURA DODSWORTH

The Terminally Ill Adults (End of Life) Bill, currently before the House of Lords, has been presented by its supporters as a measure rooted in autonomy, dignity and choice. The framing is powerful. Who could be against those values?

But beneath the surface of the language lies another story — about the way we are subtly guided, pushed and pulled toward certain decisions by structures, systems and the very design of our choices. These are what behavioural scientists call nudges. Nudges are not supposed to be coercive — they do not forbid options or impose punishments. They are, as Richard Thaler and Cass Sunstein put it in their book Nudge, “any aspect of the choice architecture that alters people’s behaviour in a predictable way without forbidding any options or significantly changing their economic incentives.”

Nudges work precisely because they are not obvious. They operate below the level of consciousness. They are subtle, otherwise they wouldn’t work. In other words people can’t avoid the influence of nudges, because nudges are not visible or obvious in all cases. They work below the level of consciousness, they are subtle, otherwise they wouldn’t work. It is a contradiction that something can both influence choice and preserve freedom of choice.

Choice architecture can involve defaults, framing, timing, ordering, reminders, messenger effects or even small changes in the environment.

Nudges are now commonplace tactics in business, education, government and all walks of life. And in healthcare, nudges abound.

Nudges in healthcare

Some nudges are uncontroversial. In hospitals, hand sanitiser dispensers are placed near doors and corridors, accompanied by posters reminding staff to clean their hands. This simple change increases compliance. In prescribing, NHS systems sometimes display the cost of drugs alongside cheaper equivalents, nudging doctors toward more cost-effective options without banning alternatives. In vaccinations, pre-booked appointments and reminder text messages nudge uptake upwards.

Nudges have also been trialled specifically in end-of-life care. Studies show that default options on advance directives — whether life-sustaining treatment is the default or not — significantly shape patient choices. One US study found that when the default was set to comfort-focused care, more patients chose it than when the default was life-sustaining interventions. These are not trivial matters; they affect whether someone ends up in intensive care or at home with hospice support.

Reports on behavioural insights in the NHS have documented nudges in appointment scheduling, referrals, medication adherence and end-of-life planning. At first glance, nudges seem benign — what’s wrong with designing decisions so that people are more likely to wash their hands, take their medicine or keep their appointment? Yet when they are introduced into life-and-death contexts, particularly at the end of life, the ethical ground definitely becomes less steady. As one doctor explained:

“Clinicians appropriately wonder if something unethical is going on here. If nudges influence choice, how can we justify it? Traditionally, nudges have been justified when they help promote the things people actually want deep down. But as we’ve discussed, in the end-of-life space, it’s hard for patients to know what exact types of medical care will best help them achieve their goals. In such cases, clinicians should rely on a standard that they have historically relied on anyway: the ‘best interests’ standard, where, absent compelling evidence about what a patient would truly want, we should act in a way that we believe — or know, based on evidence — would promote their best interests.”

Reflecting on their own practice, they described how even seemingly neutral conversations about end-of-life decisions carry hidden nudges:

“As med students, we are all taught it is important to have conversations about whether patients wanted a DNR (do not resuscitate) order. We’re told that the way to do that is to be neutral – to say something like, ‘In this situation, your loved one’s heart might stop. If so, would he want us to do chest compressions?’ But that places an incredible burden on family members to feel like they have to know exactly what their loved one would want in this specific situation — something they rarely know with confidence. And in fact this isn’t all that neutral anyway — to say no to chest compressions requires giving up something, which is always hard to do.

That strikes me as problematic in cases where chest compressions would almost certainly do more harm than good. So as I developed more experience, I became comfortable saying, ‘In this situation your loved one’s heart may stop. If it did, we would not routinely do chest compressions, because they would be unlikely to work. Does this seem reasonable?’ This way, I’ve set a default option, but I’ve not removed any options. I’ve now used this language several hundred times with the families of patients who were most certainly going to die, and only once has a family chosen CPR. Indeed, several families have thanked me for helping them understand what the norms are.”

This recognition — that nudges are already being used in healthcare, and even in end-of-life care — should give us pause when we consider what it would mean to legalise assisted suicide within the NHS.

Nudges during Covid-19

The Covid-19 vaccine rollout offers striking examples, which I wrote about at length in A State of Fear and Free Your Mind and numerous articles. I don’t want to repeat myself. But in essence it would fair to conclude that the vaccine was promoted with a unique panoply of nudges, before eventually being foisted upon the remaining unwilling unvaccinated population with mandates, varying country by country.

Whether one applauds or condemns specific interventions, the route in recent years has been the same. In the case of governments, nudges sometimes appear to be merely the first tool deployed in pursuit of a policy goal, which may continue upon an exorable path of nudges, shoves and pushes, finally culminating in cattle prods.

The comparison between vaccines and assisted suicide is not niche. The nudges used for one and potentially for the other raise urgent questions of bodily autonomy and the dangers of the state blurring the line between influence and coercion.

The conflict within the NHS

The NHS is charged with preserving life, promoting health, preventing suicide and relieving suffering. To ask the same institution to also provide assisted suicide is to create a profound conflict. On one hand, the NHS works daily to prevent suicide in people with mental illness, poverty or social isolation. On the other, it would be offering suicide assistance to people who meet the Bill’s criteria. The distinction may be clear in law, but in practice it is fragile.

More fundamentally, the NHS would find itself choosing between life and death as treatments. Life-extending care, palliative interventions and hospital stays are expensive. Assisted suicide, once established, is relatively inexpensive compared to palliative care.

The government’s impact assessment of the Assisted Dying Bill is candid about cost and savings. The projected “savings” to the NHS once it offers “assisted deaths” are up to £59.6 million per year by the tenth year, due to what the assessment calls “unutilised healthcare”. That is, care not provided because patients died earlier through assisted suicide.

The impact assessment explicitly presents assisted dying as a cheaper option. And there will be further savings in welfare and pension bills.

Once the system internalises this logic, the nudge becomes clear: over time, patients may be steered — subtly, even unconsciously — toward the cheaper, system-saving choice.

Quite simply, assisted suicide is more cost-effective for the tax payer.

The debate as a nudge

It is not only in clinical encounters that nudges will operate. The political and cultural debate itself has been structured through nudges. By framing the Bill in terms of “autonomy” and “choice”, its proponents shape public perception before ethical dilemmas are confronted. And by presenting financial savings, the impact assessment reframes death as efficiency. These are nudges of rhetoric and policy.

Disability rights groups have been vocal in opposing the Bill. Disability Rights UK said: “Assist us to live before you assist us to die.” Their concern is that vulnerable people — disabled, elderly, socially isolated — will internalise a sense of being a burden, a subtle nudge toward choosing death.

Former Prime Minister Theresa May described the Bill as a “licence to kill” that risks creating pressure on people to end their lives. The British Medical Association has recommended that if assisted dying becomes law, it should be arranged through a separate service, with no duty on doctors to raise the option with patients — an attempt to minimise the normalisation that would otherwise nudge patients toward it.

The central paradox is this: the Assisted Dying Bill is presented as enhancing autonomy, yet the very structures it creates may (surely will) channel people’s choices, not just through nudges but due to inequality in palliative care choices across the country.

In other countries, eligibility criteria have expanded and uptake has grown beyond original projections. Belgium, the Netherlands and Canada all show how normalisation changes the choice architecture over time.

Autonomy is not exercised in a vacuum. It is exercised within systems, under resource constraints and amid cultural expectations. Patients do not walk into neutral rooms where all options sit equally on the table. They arrive at consultations tired, afraid, sometimes in pain, often anxious, perhaps misinformed and quite possibly unable to access high quality palliative care due to resource constraints. They are met by doctors working in overstretched institutions, who themselves are subject to nudges, pressures and policy targets. In such a setting, the line between offering a choice and steering towards one can become thin to the point of invisibility.

This is why nudges matter so much here. They are used to shape organ donation, vaccine uptake, screening programmes, and even end-of-life care through defaults in DNR discussions. They are subtle, often invisible, and they work. To imagine that assisted dying would sit outside this pattern is naive. The NHS would be tasked with providing both life and death. When cost pressures bite — and they always do — which option will be the easier sell? Which leaflet will be in larger print? Which button online will be bigger? Which choice will be accompanied by the most flattering language? Which option will be endorsed by celebrities? Which path will feel more aligned with the “responsible” choice? Which will be more convenient and easier? The nudge will be there, and it will rarely be recognised for what it is.

Supporters of assisted dying say it is about compassion and autonomy. But compassion is not neutral when death is cheaper than life, and autonomy is never absolute when architecture shapes choice. To legislate for assisted dying is to legislate for a new form of state power over death — not by force, but by suggestion, by framing, by defaults — by nudging. And once such an architecture is built, it will not be easily dismantled.

The debate should not only be about whether assisted dying is compassionate or cruel, but about how choice itself is constructed, and who benefits when death becomes an option offered by the very system meant to preserve life. Because when the nudge comes — and it will — it will not look like coercion. It will look like choice and freedom. And that is precisely what makes it so dangerous.

This article (Assisted Suicide — Will we be nudged towards death?) was created and published by Laura Dodsworth and is republished here under “Fair Use”

See Related Article Below

Embrace hope, reject assisted suicide

Legalising assisted suicide would open a Pandora’s Box of horrors

DAVID ALTON

As many people will be aware, I was recently involved in the London bus crash in Victoria where I suffered spinal injuries. I am thankfully recovering well after receiving excellent medical care, but, sadly, my injuries prevent me from being able to speak in the House of Lords during the debate on the assisted suicide Bill. This is an issue I have spoken out against for many years, and which is currently at its Second Reading Stage. I am instead publishing the speech here that I would have given at Second Reading had I been present in the chamber.

It is worth acknowledging at the outset that the issue Parliament is considering is not a new one. Euthanasia of the weak was practised in the ancient world but was rejected as we became more civilised and recognised the equal and inherent worth of each person, regardless of ability or disability, age or capacity. It was also practised in the mid-twentieth century in the name of eugenics.

But, of course, a practice cannot be dismissed simply because of the bad company it keeps. Assisted suicide or euthanasia — a difference without a distinction in many ways — has been reintroduced in a small number of countries in recent decades, and we can look at these jurisdictions to observe what has happened and inform our deliberations in the House of Lords.

And what we can observe from these jurisdictions is a pattern of creeping incrementalism, away from their original supposedly tight eligibility restrictions, and laws which put vulnerable people at risk.

In introducing the assisted suicide Bill at Second Reading, Lord Falconer suggested that assisted suicide laws which have started as terminal illness-only laws have remained that way. However, this is misleading.

Where assisted suicide has been legalised, however tight the initial safeguards and however sincere the assurances that it would be a narrowly defined law for rare cases, the practice has tended rapidly to expand.

Sometimes this is by a clear expansion of the law, such as in the Netherlands and Belgium where assisted deaths are now permitted for children of all ages and have been granted for tinnitus, autism and dementia; or in Canada where it only took five years from the introduction of euthanasia and assisted suicide in 2016 for those whose death was “reasonably foreseeable” — in other words, who were terminally ill — to an expansion to the ill-defined and subjective “serious and incurable illness” criteria in 2021. And Canada has now not only approved the euphemistically-named “Medical Assistance in Dying” for people with mental illness from 2027, but there is also a push to join the Netherlands in allowing infant euthanasia for severely disabled babies. This is not progressive but regressive, a return to pre-civilisation.

In other jurisdictions, the law has expanded by stealth, by the interpretation of “terminal illness” being broadened. For example, in Oregon in the US, a state held up as a model for the law proposed here, people have been approved for assisted deaths with diabetes, arthritis, a hernia and, perhaps most disturbingly, anorexia.

Even if we were to permit assisted suicide with an initially narrow scope, there is a danger of human rights challenges whereby courts rule it is discriminatory to allow assisted suicide for some groups of people but not others, similar to what happened in Canada. Once you permit the practice, you cross a moral and legal Rubicon and it is hard to control the consequences as different groups demand “access” to the same provision. Even last week in the House of Lords, one of my colleagues expressed support for a wider law.

The countries I have cited are not rogue states. In many ways, they are like ours. And yet they have not been able to prevent a rapid expansion in the law or increase in the number of people who die under laws that are sold as being for exceptional cases. In Canada, in 2023, nearly 5 per cent of all deaths were from euthanasia or assisted suicide — over 15,000 people in a country with a population smaller than ours. This is a warning to us.

Other countries have learned these lessons. In Denmark, in 2023 the Council on Ethics looked at this issue and concluded, by a majority of 16 to one, that it was “in principle impossible to establish proper regulation of euthanasia” and recommended to the Danish Parliament that the law should not be changed. We should heed their warnings.

In light of what we have seen elsewhere, I contend the only safe approach is to keep the current prohibition on assisted suicide

Indeed, during its inquiry into assisted suicide two years ago, Dr Lydia Dugdale, Director at the Centre for Clinical Medical Ethics at Columbia University, warned the Health and Social Care Select Committee that “As soon as [assisted suicide] is legalised it expands. The language shifts; it goes from ‘guardrails’ to ‘lack of access’. That is very pernicious. Guardrails are there to protect society more broadly and to keep us from becoming a death-inducing state”.

In light of what we have seen elsewhere, I contend the only safe approach is to keep the current prohibition on assisted suicide, while investing in improved palliative care to support the thankfully very rare cases of people who suffer greatly at the end of life.

I note that the House of Lords Constitution Committee has joined the Hansard Society in confirming that the House of Lords has every right constitutionally to reject this legislation if it believes, as I do, that it would endanger vulnerable people, whether those who may face subtle, often undetectable coercion, such as the victims of domestic abuse or people with Down’s syndrome, or the “self-coercion” of those who feel a burden and will think they have a duty to die if a so-called “right to die” is introduced.

In summary, Pandora’s Box has been opened in countries where assisted suicide or euthanasia have been legalised, and the sad consequences are plain for all to see. Once Pandora’s Box has been opened, there is no going back. We must not proceed along this path if we have any doubt about the consequences.

According to Greek mythology, when Pandora opened her box and unleashed all kinds of ills on humanity, she closed the box before the last thing was able to escape — that thing was hope. Hope is what we need to offer people instead. Assisted suicide is chosen by people who have lost hope — who lack any reason to go on living. Passing this Bill would send a tragic message that sometimes there is no hope and some lives are no longer worth living.

But it does not have to be this way. By investing in social care, by continuing to be a world leader in palliative care and expanding access to it, by being a society that respects life and upholds the dignity of the elderly and people with disabilities, we can give hope to the hopeless and create a society where people can die with true dignity, not by ending their own lives. That is the kind of society we ought to be striving for.

••••

The Liberty Beacon Project is now expanding at a near exponential rate, and for this we are grateful and excited! But we must also be practical. For 7 years we have not asked for any donations, and have built this project with our own funds as we grew. We are now experiencing ever increasing growing pains due to the large number of websites and projects we represent. So we have just installed donation buttons on our websites and ask that you consider this when you visit them. Nothing is too small. We thank you for all your support and your considerations … (TLB)

••••

Comment Policy: As a privately owned web site, we reserve the right to remove comments that contain spam, advertising, vulgarity, threats of violence, racism, or personal/abusive attacks on other users. This also applies to trolling, the use of more than one alias, or just intentional mischief. Enforcement of this policy is at the discretion of this websites administrators. Repeat offenders may be blocked or permanently banned without prior warning.

••••

Disclaimer: TLB websites contain copyrighted material the use of which has not always been specifically authorized by the copyright owner. We are making such material available to our readers under the provisions of “fair use” in an effort to advance a better understanding of political, health, economic and social issues. The material on this site is distributed without profit to those who have expressed a prior interest in receiving it for research and educational purposes. If you wish to use copyrighted material for purposes other than “fair use” you must request permission from the copyright owner.

••••

Disclaimer: The information and opinions shared are for informational purposes only including, but not limited to, text, graphics, images and other material are not intended as medical advice or instruction. Nothing mentioned is intended to be a substitute for professional medical advice, diagnosis or treatment.

Disclaimer: The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of The Liberty Beacon Project.

Leave a Reply